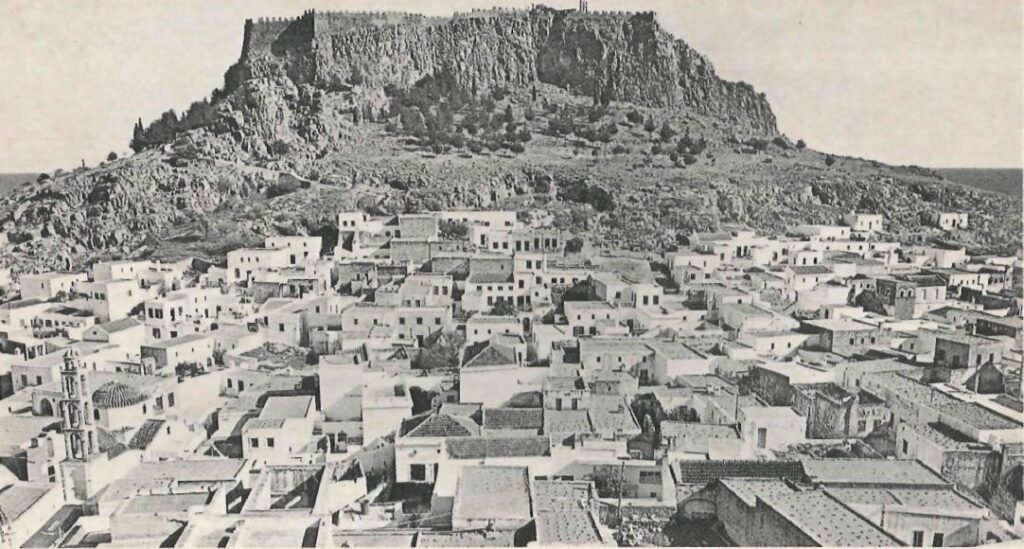

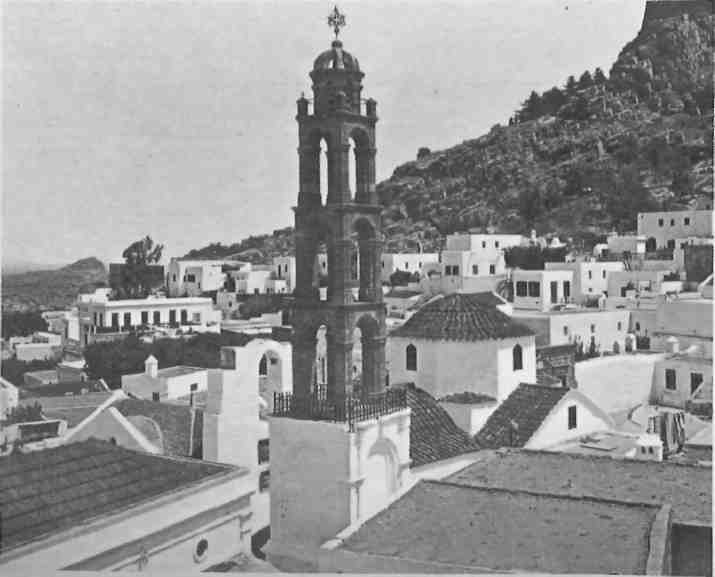

There were all those white houses that lay scattered under the commanding Acropolis like a handful of confetti. Then there was the bay of Lindos, blue as a butterfly’s wings, sitting in the sunlight beneath the village, enclosed by horns of rock, two islands guarding its entrance. The air was fragrant with the scent of wild herbs, fishing boats lay bobbing at anchor, and kestrels surged across the sky. It all seemed to have been put together for a postcard.

But when we entered Lindos we quickly learned that it had a more practical, down-to-earth side. In looking for a house to rent we met a German artist who was living there. The first thing he said was, “Of course Γ11 help you find a house. But remember, you must not spoil things for the rest of us. Don’t pay more than ten dollars a month rent.”

After settling in, it didn’t take us long to learn that Lindos had not been built for picturesque effect.Basically, Lindos was conceived as a fortress-town. Even as recently as a hundred years ago the Aegean was by no means free from pirates; the last pirate raid on Lindos took place in 1875. Thus the labyrinthian streets, the enclosed houses, the high walls and tower bedrooms all served a very real purpose — as defense against marauders.

The impact of earthquakes on Lindos must also be taken into account.Most of the medieval houses postdate the great earthquake of 1481. Consequently much of the town has been deliberately designed to withstand another quake. Streets and houses follow the natural contours of the ground. The houses are packed together, but for a reason. By staggering the floor levels of two back-to-back houses and using common walls between the main rooms to form terraces, a strongly earthquake resistant construction has been achieved.So cleverly has this engineering feat been accomplished that no one courtyard overlooks that of another house. Not only safety but privacy is thus maintained, and with an eye for beauty and harmony.

There are other reasons why Lindos remained virtually untouched over the years. Because of a sharp decline in prosperity in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, there was no money for rebuilding or “improvements”. Then came the Italians, who occupied the island of Rhodes in 1912 and later turned it into a military and supply base to buttress their dreams of establishing an Italian hegemony over Asia Minor. The road they built from the city of Rhodes, thirty-three miles away, terminated in the village square, and so all vehicular traffic was kept out of the interior.The island was returned to Greece in 1948.

When we first arrived Lindos was still extremely poor. Only a handful of the town’s six hundred inhabitants managed to scratch out a subsistence fishing or farming. The rest did odd jobs and existed mostly on checks from relatives who had emigrated to various corners of the world. Tourism, however, was in an incipient stage and no doubt the next years would have seen the first high-rise hotels and “apartels” going up, the same concrete carbuncles that lie like an abomination on so much of the Mediterranean seacoast. Lindos was spared that tragedy. The entire village and the surrounding area was declared a national monument, and the Archaeological Service was given responsibility for preserving its character.

Living in an undeveloped village had its disadvantages, of course. We had to haul all our drinking water from the square. There was only one refrigerator in town and meat was available only once a week, on Sunday, when the butcher killed an over aged goat. We soon became accustomed to the inconveniences and found ourselves enjoying life as never before. Is there anything better than sitting in a sun-drenched courtyard under a vine-covered trellis with bunches of purple and green grapes, and making a lunch of fresh-baked bread, fresh eggs, yogurt, tomatoes, onions, lettuce, with a delicious and inexpensive local white wine?

Our first years in Lindos were years of discovery. We lived in a house with no electricity and hardly any furniture, just a few tables and chairs, a seaman’s chest, an odd piece of cutlery or two, but we didn’t mind. Our skin became deeply tanned and our hair coarse with salt and very bleached. We began to learn Greek and to discover the rhythm and subtleties of the village life.

In those days life was a lot slower and more amiable than it is today. We all worked hard, but I spent many an afternoon skindiving and spearfishing with friends, hiking to a different spot each day. (It proved a painless way of exploring the historical landscape around Lindos). There are few days, even in winter, when the sun does not dominate the landscape of Lindos, constantly changing the colour and texture of the houses, rocks and water. The pelagic depths of the sea act like stained glass on the shafts of light which penetrate its depths, breaking them up into gently shimmering spangles of gold. On these days the sea becomes transformed, turned into a cathedral, a holy place of silence and awe and luminescence. Sometimes it seems almost a blasphemy to be hunting for octopus and grouper down there.

Over the years a trickle of foreigners, mostly writers, painters and other creative people, came to Lindos to join those already there, giving the village a flavour that falls somewhere between Nikos Kazantzakis and Ken Kesey.

And then, quite suddenly and in great waves, especially in the summer, came the tourists, and Lindos, after years of lying in a torpor of heat and idleness, was swept practically overnight into the jet age.Nearly everyone who visits Rhodes makes the hour-and-a-half bus trip to Lindos, the island’s official beauty-spot, to climb the Acropolis, walk the winding streets, eat, shop and perhaps enjoy its pretty crescent beach. Some decide to stay awhile, renting rooms in private homes, the only accommodations available.

The visitors leave a lot of money in their wake, and the money has done wonders to the standard of living in the village. Practically every house now has running water and electricity. All the public services have been improved — postal, banking, rubbish collection and telephone. New tavernas and restaurants have opened. Many Lindians have learned to speak English, Swedish, and German, and they can now afford to send their children to the university and technical colleges in Athens.

Tourism has brought more than just material benefits. No longer do the men of Lindos need to emigrate to Africa, America, and Australia to find employment. The flow has been reversed and many expatriates are returning home to work or start small businesses. Prosperity has also prevented the local folk arts from dying out.

But accompanying all this has been an upward spiraling of costs. Eighteen years ago in Lindos one could buy a house for as little as six thousand dollars. Today the title to a house which is little more than a pile of old rocks might cost thirty thousand dollars and double that to restore it.Things are further complicated by the fact that no foreigner is permitted to own property in the Dodecanese; he must make the purchase through a proxy Greek owner.

Still, the houses continue to be snapped up, which creates a problem for local families: having sold property to the foreigners at outrageous prices, the Lindian now finds he must bid at the same level when it comes time to find a house for his daughter’s dowry. In Lindos a girl’s dowry still forms the basis of the marriage contract, and a key factor in the dowry is a house. The number of Lindian men prepared to marry a girl without one is negligible, although the title to the house remains in the wife’s name, even after marriage. Ownership of most private property in Greece descends matriarchally.

Moreover, even those families who have provided their daughters with an ample prika (dowry) are finding it hard to marry girls off. As ex-Mayor Stephanos Pallas reminded me recently, there hasn’t been a wedding in Lindos in two years.

“It’s because of the foreign girls,” he said. “The village boys have become so accustomed to enjoying their favours, that they won’t have anything to do with the Greek girls. It’s getting to be a serious problem. We have families with two or three eligible daughters on their hands, girls who are spoiling on the vine.”

Life in Lindos is certainly becoming more and more complicated these days. The familiar old ways have begun to lose their authority; they are no longer able to fulfill the religious, moral, intellectual and social demands of the contemporary generation. People’s roots are being torn up, their loyalties confused, their identities challenged. There is a real danger that Lindos may be destroyed in the process of becoming a popular retreat.

The question is, can the village still retain its unique beauty and character in the face of these pressures? Is the local culture strong enough to resist the indefatigable tide of foreign visitors and owners? There can be no absolute answers at this time, but history informs us that Rhodes has been through this many times before and the local culture is a deceptively tenacious one. If Sultan Suleiman or Mussolini couldn’t kill it, then, one hopes, neither will the package tours of our time.