The truth lay somewhere between these theories, we learned soon after arriving in Langada, a rural village just north of Thessaloniki. The “Anastenarides” congregate here every May to practice their rites of fire-passage. The first thing that strikes you about the Anastenarides is how far they are from being pagan or satanic. On the contrary, the firedancers are devout Christians who never brave the coals without a sacred icon or relic in hand of St. Constantine or St. Helen whose feast day is on May 21. In life they are the most ordinary of people — farmers, housewives, shopkeepers, butchers. They are only exceptional when they answer their “call”, the need to demonstrate their love of God (and the power of their saints) by walking on fire.

Last year, we watched them perform three nights running, before a crowd of two or three thousand people, each of whom had paid an admission charge to witness the event. But the charge was small — a few drachmas — and most of the money went to the three musicians (bass drum, two lyres) to cover the costs of their week-long stay in Langada. The dancers not only drew no money, but often danced during the day, among themselves, when the spirit moved them — and when no one else was watching. Their motivation was at all times spiritual, not pecuniary.

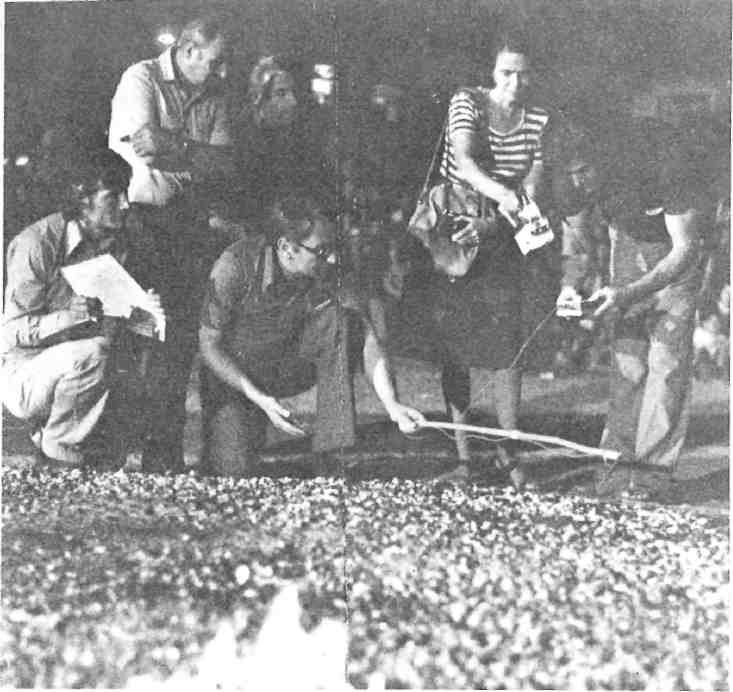

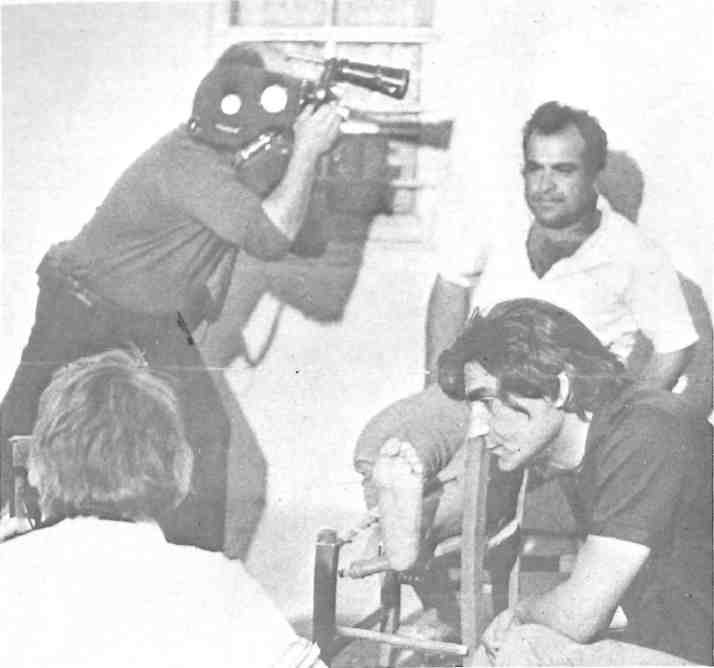

The only carnival folk at the proceedings were in the audience. Each night at least one or two persons rushed from the stands and tried to walk the coals with the firedancers, in an attempt to upstage them. (They invariably ended up in the hospital with badly burned feet, of course.) The most sceptical observers on the scene, however, were a team of Germans making a television film on the dancers and eager to expose the “tricks” involved. Most of the Germans were medical researchers backed up by a van-load of testing equipment. The Anastenarides could not perform until the Germans tested the temperature of the coals or measured the thickness of the calluses on the dancers’ feet. The head of the group was a doctor who kept badgering the dancers to sit still long enough for him to run psychological tests on them.

“If I could just get one of them to take a Rorschach test,” he said, “I’m sure I could find the pattern of mind-body discipline that aids them in unleashing their awesome powers of psychomastery over pain.”

Through it all the firedancers managed to retain their equanimity and humour. They simply shook their heads at the crazy foreigners, with their cameras and thermometers, and went about their devotions as they and their ancestors have been doing for at least a century.

There is no evidence that the history of the Anastenarides goes back much further than that. The scholars who have traced their lineage back to pre-classical times have never been able to prove their case. It is a popular misconception that the Anastenarides are continuing an age-old pagan rite when they dance. Their roots probably go back no further than the 1800s, when the phenomenon of their firedancing was first observed in Thrace and Macedonia (notably in areas that are now part of Yugoslavia and Bulgaria).

No one, not even the Anastenarides themselves, can explain how they first began dancing on red-hot coals. Probably the rite sprang up as a reaction to the economic and religious oppression they suffered at the hands of the Turks. What better way to cling to their faith and express both devotion and defiance than by walking on fire? Ironically, the hierarchy of the Greek Orthodox Church has always been leery of the dancers and has even made unsuccessful attempts to suppress the firewalking ritual entirely.

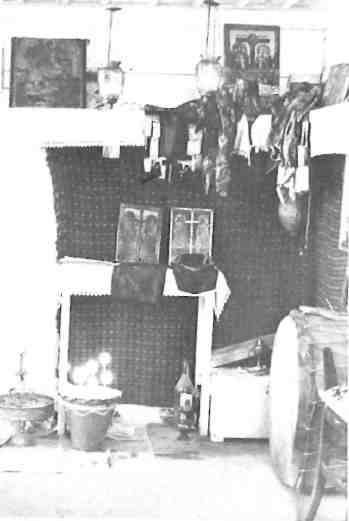

The Anastenarides are therefore a small but determined band of initiates. They are a patriarchal order, ruled by a “chief”, in this case a wizened old farmer in whose home all the preparations for the nightly dance took place. The group’s icons and relics were stored with him in a simple back room. Those Anastenarides who had come to Langada from other parts of Greece also slept and ate there.

The firedancers were accompanied by friends and relatives, children and grandchildren. Some but not all members of a family were actual firewalkers. There was no pressure from anyone to force a loved one to risk the coals. As one of the dancers said, “You know inside when it has come time to dance.”

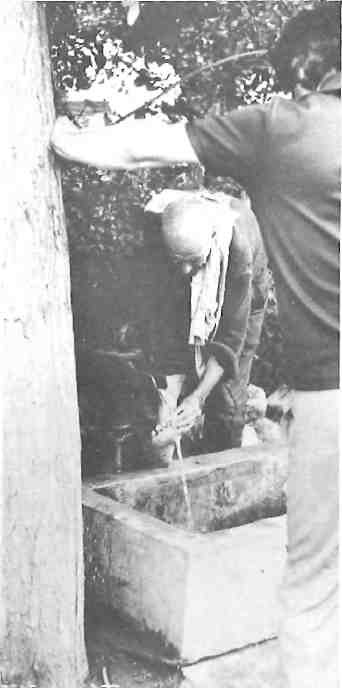

Walking over the fire was only one way the Anastenarides had of asserting their holiness. Following the ritual slaughter of a bull and goat, they prayed, then danced within the confines of the chief’s farmhouse. The musicians were always with them, the pounding of the big goat-skinned drum and the counterpoint of the lyres gradually becoming urgent, hypnotic. The dancing varied between circle dances and solos, with the beat of the drum increasing in speed and intensity, and the dancers uttering short, excited gasps and cries as they whirled. (Hence the name, Anastenarides, from anastenazo, to sigh.)

During the day, a small fire was lit. Those who felt the need walked and skipped across the coals. But at no point did the dancers ever work themselves into a frenzy. One minute they seemed to be in a partial trance, or a state of ecstasy, the next they would catch sight of a favourite grandchild and flash a big smile, or even blow a kiss. They seemed able to go in and out of their ecstatic condition at will. When asked how they could do it so easily, the dancers just shrugged and said, “The saints look after us.”

It was the same at night, when they braved a circle of coals a good twenty feet in diameter. There was a lot more tension, even hysteria, in the air, what with the thousands of milling, largely-sceptical and hostile onlookers, and the television lights, the whirring film cameras. The dancers arrived at the field after having marched in procession through the village to the accompaniment of the steadily beating drum, the high-pitched lyre, children and dogs running and yapping behind them.

The sight of that huge bed of coals glowing vividly in the dark brought a stab of fear. The dancers were tense, keyed-up, but certainly not in a stupor. Not one of them had drunk anything harder than water, or taken any kind of drugs. They were armed and aided only by their icons — and their faith.

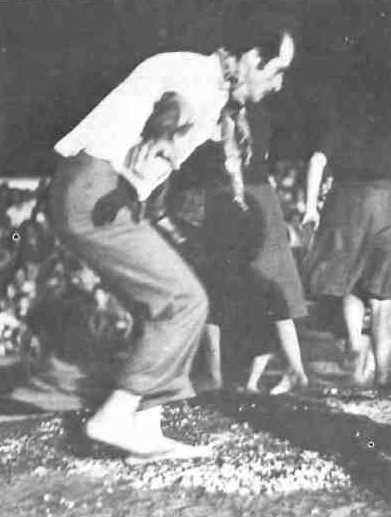

First the dancers circled round and round the fire, kicking up the dust, uttering their characteristic and piercing cries and yelps. A woman stood off to the side, singing the ballad of St. Helen and St. Constantine. Then the chief, looking tight-lipped now, but youthful and agile, suddenly skittered barefoot across the coals. The crowd gasped, hardly able to believe what they were seeing. No sooner did the old man finish one traverse but he started another, feet driving deep into the fiery coals, kicking up sparks. With his two flights, he seemed to be outlining the shape of a cross. But he would not confirm or deny this later. The Anastenarides have their secrets.

Then the other dancers — about twenty in all — began crossing the bed of coals, some arm in arm, others alone, yelping all the while, making their cries heard above the high-wailing music and song, holding their icons and relics high. Some stopped in the centre of the coals to stomp their feet like fandango dancers, others seemed to skim the coals like low-flying birds. Many of the dancers only crossed once or twice, others crossed again and again. Several of them bent down and actually picked up the coals in their hands and pressed them to their cheeks, lovingly. Then with a cry they flung the coals away like confetti and resumed their joyous sweeps across the glowing bed. The dancers ran this way and that, sometimes bumping into each other, going faster and faster as the music and song soared and dipped, dipped and soared.

The fire dance did not last long, perhaps ten or fifteen minutes, but by then the crowd was with them each time they flew back and forth over the fire, their ecstatic cries filling the air. The dancers had become animated, transformed, but just as it seemed they had entered a hypnotic state, you would catch one cracking a joke to another, and laughing.

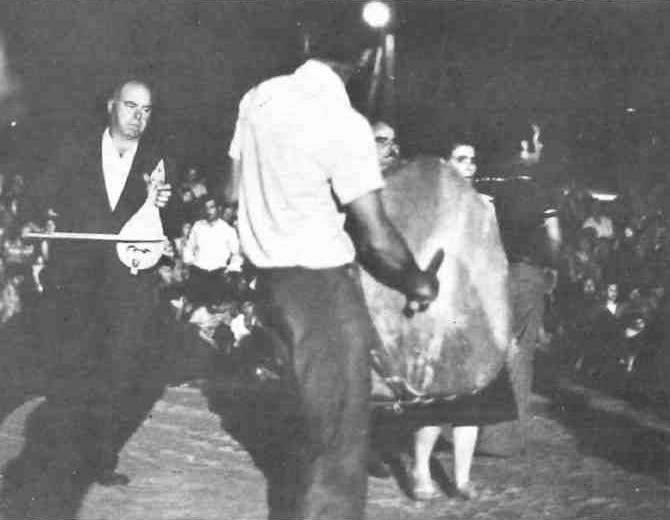

The heat of the coals — strong enough to drive me back continually from where I kept edging to take photographs — did not bother the dancers at all. What disturbed them most were the intruders — “fire-crashers”. Whenever an outsider tried to join them on the coals, they would angrily try to drag him off. It would lead to an altercation which the police had to settle each time. Some observers kept goading the dancers to allow an outsider to join them, but they would have none of it. It was their night and no one else was cutting in on it.

But these unpleasant flare-ups did not detract from the miracles taking place. One lady fire-dancer, for example, skipped over the coals in her stocking feet. The Germans immediately checked her out. Her stockings were intact, not even scorched.

The chief did not keep dancing. After his first flights, he stood on the sidelines watching over everything. Whenever a dancer seemed to be working himself into a frenzy, the old man would restrain him with a nod of his head, a quick little gesture. Immediately, the dancer would drop out, sometimes even sit down. The chief paid particular attention to the new dancers. Those taking the journey for the first time went arm in arm with oldtimers. They never attempted their baptism of fire alone.

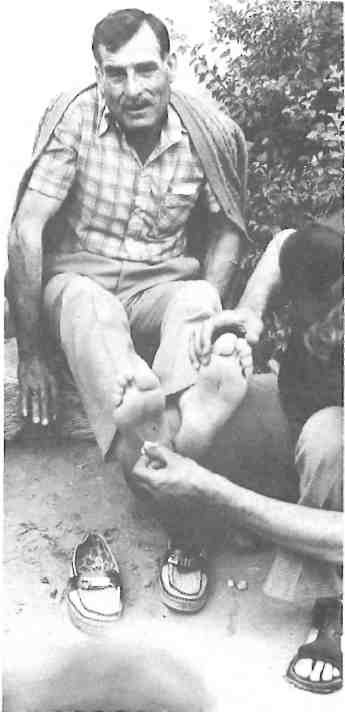

And then it was over. On a signal from the chief, the dancers regrouped and left the field, still doing a kind of shuffle-dance in time to the beat of the drum. Back to the chief’s hut they went, to cool off and rest. Then the television crew arrived, to once more, examine their feet, and put calipers to their calluses. Friends and strangers alike came to embrace them, thank them for the spiritual gifts they had passed on tc the community at large, acknowledge the miraculous powers of these people and their icons.

Hours later, after everyone had left, the dancers shared a simple meal on the floor of the chief’s hut. Toward dawn religious feelings took hold of them again. They asked for music and song, soon began to dance, to build another fire over which to once again express their joy and devotion.

It went on like that for three days, an almost unbroken time of celebration and communion. When it was finally over, the German psychologist was there to corner the chief, to ask to see his feet one last time. The old man gave an exasperated sign and muttered an expletive. But then he finally sat down and pulled off his dung-stained rubber boots. He displayed two absolutely normal soles to the professor, who then asked him if he had felt any pain at all while risking the coals.

“The fire can never hurt me,” the chief said for the fiftieth time that week. “The saints protect me when I dance.”

The psychologist suddenly whipped out a card with an ink blot on it. “What does this remind you of? Please tell me,” he begged. The chief looked at it, then at Herr Director. Then he put his head back and began to laugh, and laugh, and laugh.

Firewalking rites will take place on and around May 21 at several locations in Greece. Details are in the listings section of this issue under “Round and About”.