Having reported on the Cyprus issue for many years I feel I know the country, but arriving here for the first time is a strange experience. I do not feel as though I am in Cyprus. Nor do I know what I expected. An alter-image of Greece, which it is not? Even after several days, after seeing the city, driving to the mountains, meeting people in their homes, dining in restaurants, an answer eludes me. There are sections that remind me strongly of Bermuda, of the Bahamas, or other places where the British have settled and retired. Yet, the houses look less affluent, the gardens less lush. Driving on the mountain roads in the Troodos range I am reminded, strangely enough, of travels in Haiti.

When my host gave me a map of Nicosia before I set off on my first peregrinations, I had visions of an old Italian city with crenelated walls, mellowed by age. These visions quickly vanished. Crossing one of the busy bridges that span the moat surrounding the old section, the remnants of the fortifications are hardly noticeable. Entering the old city, there is little change in the appearance of the streets: there are shops inside and shops outside, and modern buildings mingle with old buildings in both the new city and the old.

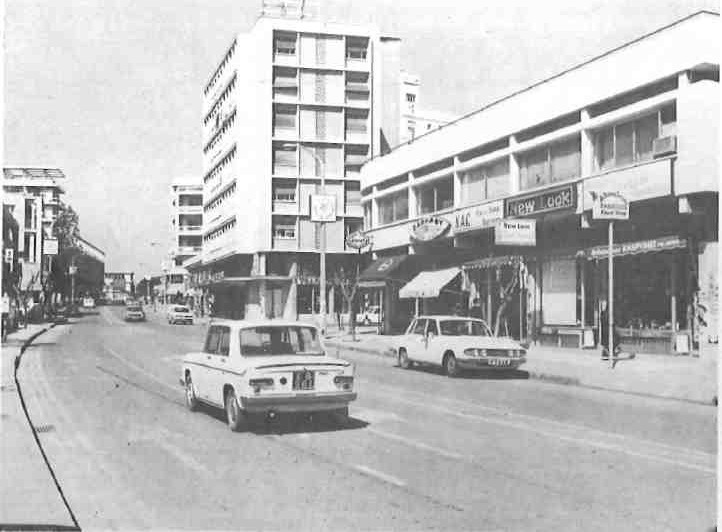

The shops, the people in the streets, the new apartment blocks, show a degree of provincial prosperity. The city is clean, the streets well-kept, and the shop windows testify that one can find anything.

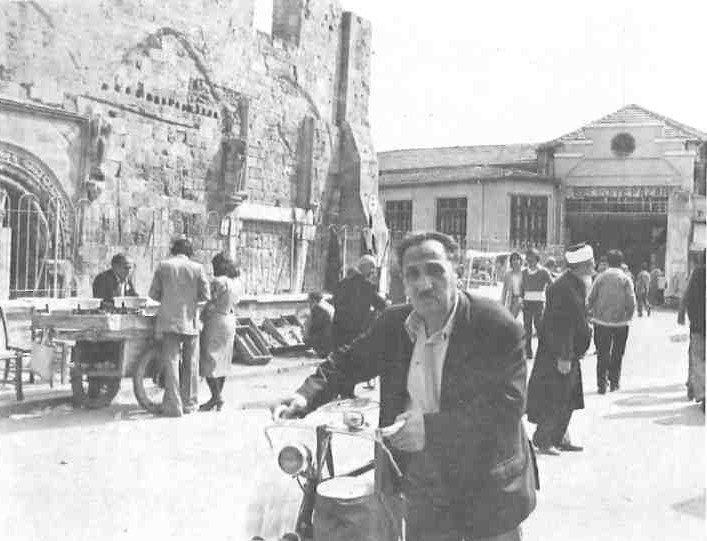

This impression changes quite rapidly crossing over into the Turkish sector at the Lydra Palace Hotel checkpoint. The families waiting at the checkpoint remind me of the Berlin Wall, although there is no wall. The sight of waiting people—mostly women and children—talking to their relatives on the other side is no less depressing. One suddenly has the feeling of being in an old city. And in a different country altogether. In contrast to the modern, commercial area on the Greek side, it seems more like a peasants’ marketplace. Turkish soldiers are patrolling the streets. It is a sunny Saturday morning, and most people are shopping for the weekend. There are vendors selling fish and various produce and tucked into the entrances and hollows of old, dilapidated buildings are shops selling the spices and wares of the old Arabian souks.

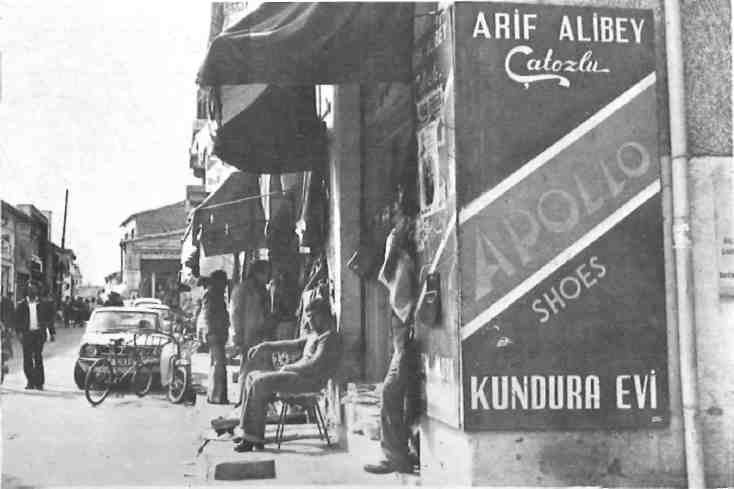

Posters with patriotic Turkish slogans cover the alleys and passageways. They depict soldiers with rifles and bayonets. In between are advertisements of a less-martial character. One of them praises the attributes of “Apollo” shoes. I try to locate a copy of the Cyprus News, an English-language weekly published on the Turkish side of the island. The most recent edition I can find is over a week old. I have only a large bill and the bookshop can give me change only in Turkish pounds, the official currency now in the Turkish sector. As I back out of the sale, the clerk in the bookstore expresses, in very good English, his surprise that I will not accept Turkish money. He pleasantly suggests that I read the paper in the store, without charge.

The plane from Athens to Larnaca last night had been full of German tourists destined for Paphos. My curiosity aroused by such a strong showing of tourists so early in the season, I decide to make inquiries while in the northern section of Nicosia about the nationality of tourists coming to Famagusta. But my efforts fail. At the official Turkish airline office I find, after speaking in English, German and French, that only Turkish is spoken. Finally I am handed a few travel brochures in English on Girne (Kyrenia), Lefkosa (Nicosia), and Magosa (Famagusta). I was to learn later that most of the tourists are from mainland Turkey.

During discussions with Cypriots, including politicians and journalists, and with members of the foreign colony, I learn that life in the North is hard. Prices are exorbitant, even for those with above-average incomes, and were exorbitant even before the recent devaluation of the Turkish pound. The countless Turkish soldiers conspicuous in the North are not a strain, however, bn the Turkish budget, as one might assume. “They live off the land to a great extent,” one journalist tells me. The cost of maintaining them in Northern Cyprus is no greater than maintaining them on the Turkish mainland.

I ask about making professional contacts in the North with administration officials and journalists. A colleague tells me that the Journalists’ Union sent a letter of invitation to their confreres in the North to get together for a meeting. The letter was sent six months ago. To this day there has been no reply.

Politically there is said to be a growing opposition to Rauf Denktash’s hard-line stance. Alper Orhun, the leader of the Populist party, the major opposition party in the North, has openly accused Denktash of not “allowing” Ecevit to offer more liberal terms of negotiations. At the same time it is believed that the opposition will come around to the “official” line. The Turkish Cypriots, it is said, are not very vocal in the political debate. But the recent resignations of both “Premier” Necat Kunuk and “Foreign Minister” Vedat Chelik in the North (their government is not officially recognized) seem to bear out the indication that not all is well in their administration.

Meanwhile the Cyprus problem does not seem to be any nearer to a solution. There is, among the Greek Cypriots, a growing concern that a new problem will eventually have to be faced — that of “getting used” to the situation. Nobody is openly admitting it, but people are finding ways of making concessions. It is too early to speak about a new generation which has grown up with a fait accompli. Yet, this has been the case in other parts of the world, and finding solutions does not grow easier with the passing of years.

In the aftermath of the Larnaca incident, discussions invariably involved the question of how it could have happened. Why was nothing being written about the Palestine Liberation Organization’s presence in Nicosia before the incident? Why had Greek Cypriot papers failed to report on their activities, that they were being allowed to train on the island, and about Makarios’s open-door policy towards all Arabs? One observer suggests that it was a price paid for all the money that poured into Cyprus with the arrival of the Lebanese. Officials reply that Arabs play a small role on the island. The PLO representation does not consist of more than a handful of individuals, it is said, and indeed they keep a very low profile. Officially they are said to enjoy the same freedom of movement as everybody else. “And in a free society that is how it should be,” an official stressed, admitting that perhaps in the future “we will have to be a little more careful”.

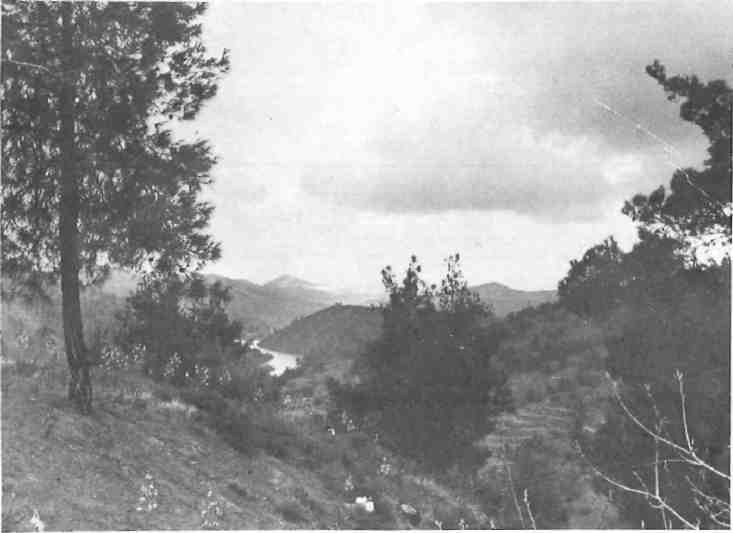

On a trip to the Troodos mountains a heavy rainfall disrupts the sunny, spring weather. We wind our way up through freshly rain washed woods looking for a dry spot to have a picnic. We had chosen Kikko Monastery, the place where Makarios is buried, as our destination, little realizing what a long trip it is. After passing the last village and discovering that we had another six miles to go, we almost give up, as the car is enveloped by blinding rain. No breathtaking view, as certainly there must be in good weather. I feel as though I am driving in Northern Europe rather than in sunny Cyprus. The villages look sad this morning; I assume it is the weather and the cold. The freshness and whiteness to be found in Greece’s countryside is absent. The village houses look closed-off to the outsider. They bring to mind remarks made by foreign friends who have spent considerable time on the island and who still, despite their efforts, feel that there are barriers to communication.

There is, in fact, still an aura of colonialism in Nicosia, in the life style and trappings of the foreigners stationed on the island, who work in isolated offices, shop frequently in special commissaries, and meet again and again at the same parties. Confined by the same boundaries, there is little opportunity to avoid each other. Weekends mean mostly excursions to the countryside and picnics with friends, usually from the same office. Everybody knows everything about everyone else. If one leaves the island for a weekend in Beirut, or Damascus, everybody seems to hear about it.

Although far more mobility is enjoyed by the foreign community than by the local population, an occasional regret is expressed because it is no longer possible to go to those “magnificent beaches on the Karpas, now in the Turkish sector. Generally speaking, those who knew the island before the division say they had friends among the Greeks and the Turks, but now Cyrpiots are keeping to themselves. They feel it is not the same any more.

~~

There is some superficial socializing between the foreign community and some of the Cypriots who “count”, but on the whole exchanges are restricted and a small-town atmosphere, something akin to a colony in a tropical post, pervades the foreign community, fermenting an inescapable closeness. To an observer removed from the real problems of the land, life appears easy and, except for partying, not strenuous.

The United Nations headquarters located on the outskirts of town on the old airport road is run with military precision, with barracks and officers clubs, enlisted mens facilities, hobby clubs organized to reduce the boredom, supply departments, and a preponderance of signs and directions in incomprehensible military jargon. It could be any military base in the Sinai, in the Golan Heights, Gibraltar, or in Kansas. Except that most of the civilians attached to the UN agree that, even though divided, Cyprus is a more pleasant place to spend one’s leisure hours than the Sinai, the Golan Heights, or the plains of Kansas. That their social standing and prestige are infinitely more elevated is some modest compensation for not being able to swim off the coast of the Karpas.