“More than half of my patients suffer from psychosomatic problems,” explained a prominent Athenian physician. “Their parents went to priests, lit a candle, and made a vow in front of the icon of their patron saint. If we only had an institution that could absorb those many patients who no longer believe in the efficacy of prayer.”

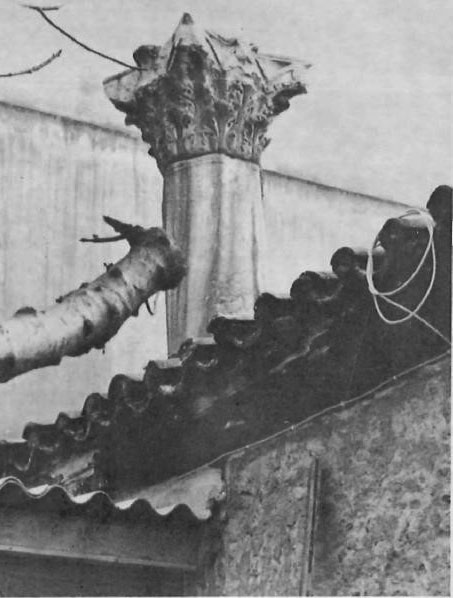

The extent to which modern life has encroached on age-old traditions is illustrated by the fate of the tiny chapel dedicated to Saint John the Baptist and known as the Shrine of St. John of the Column (Agios loannis stin Kolona) at 70 Evripidou Street, between Athinas and Menandrou. Built around an ancient column whose Corinthian cap-ital protrudes from its roof, the chapel has been described as a “tiny jewel box set around antiquity”. Until recently, many used to visit the chapel, particularly around August 29 the feast of the beheading of St. John the Baptist, and many attached threads to the column believed to cure certain illnesses.

The length of the thread was determined by the width of the waist of the worshiper who would make the sign of the cross with the thread before the icon of St. John. Then the thread was worn for three days around the waist after which it was removed, taken to the chapel, wound around the column and fastened with wax. This was accompanied by the statement: “As I leave here this thread, so I also leave here my fever.”

There is a long tradition in the Eastern Mediterranean of belief in the therapeutic qualities of columns, which includes the sweating column of St. George in Saint Sophias in Istanbul, and the numerous fragments of the Column of Scourging with which Jesus Christ is associated. The origin of the pillar cult at the Shrine of St. John, like that of so many cults, is shrouded in mystery. One theory suggests that St. John’s predeces-sor was the physician Toxaris, who came to Athens from Scythia which comprised, in ancient times, parts of Europe and Asia and is today a region of the USSR. His medical advice was said to have rid the city of a plague. After his death, the Athenians in gratitude bestowed on him heroic honours, and a column dedicated to him was erected near the Dipylon on the left side of the road leading to the Academy. The lower part of the column was regularly decorated in tribute to the many healings with which he was credited.

Kyriakos S. Pittakis, the prominent nineteenth-century Athenian anti-quarian, was convinced that the Scythian was the forerunner of the Christian saint.

Whether the Athenian healing cult associated with St. John’s column really had its origin in the classical past is difficult to ascertain, and folklore has contributed other explanations for its origins. According to one such story, St. John was associated with fever because of the ague-like trembling of his body when he was beheaded. According to another story, all those who were present at Herod’s banquet when the saint’s head was brought in on the charger were attacked by a fever which did not leave them until they had prayed to the saint for healing.

The earliest reference to the column appears in the travel journal of Jacob Spon and George Wheler published in 1678. Spon indicates the column on a map which places it at what was then the northernmost part of the city. George Wheler merely alludes to it indirectly in his written account, stating that the cathedral of Athens was situated in the northern part of the town between St. John’s column and the bazaar. The first detailed description was given by an English archaeologist, Edward Dodwell, who worked in Greece from 1801 to 1806:

“At the northern extremity of the town is a single plain Corinthian column of Euboean marble, and of considerable dimensions,” he wrote. “It stands in its original position, and as there are no other remains near it, and as it is of coloured marble, it probably never formed part of any building, but supported a statue, like the Corinthian column in the Roman Forum, which was surmounted by the statue of Focas. The Greeks have dedicated this column to St. John, and a poor Albanian woman who lives near it piously supplies a lamp with oil, which is placed in a hole of the column every night.”

The column of St. John within a sanctuary is first mentioned by Pittakis, the author of L’Ancienne Athenes, published in 1835. He noted that the cult came under ecclesiastical organization in the first half of the nineteenth century. Excavations on or near this site had unearthed a large Ionian capital and other antiquities, and Pittakis concluded that the healing cult associated with the column of St. John was a continuation of an ancient tradition. By the middle of the nineteenth century, several visitors to Athens described pilgrimages being made to the Church of St. John of the Column where those suffering from fevers offered candles and even tufts of hair.

In 1892, the noted British diplomat James Rennell Rodd, later the first Baron Rennell and author of Customs and Lore of Modern Greece, wrote: “This column is looked upon as exerting a magical and miraculous power over fevers and other diseases. In August and September when fever is rife, patients throng to it, and fastening a silken thread to the column with a piece of wax, have the firm conviction that the fever will be drawn out along the thread and into the column.”

The chapel is no larger than three metres by four. It has a representative collection of nineteenth and twentieth-century icons, and its walls are adorned with paintings of saints. A little store, selling candles, votive offerings, and reproductions of icons, is administered by a nun. On special days the miraculous icon of St. John the Baptist is placed for veneration in the outer court. But two years ago the chapel was redecorated and the column is now hidden behind the iconostasis beyond the reach of worshipers.

Superstitions of this kind have no place in our religion,” one of the elders told me. The column may now be seen only through the Royal Doors of the altar.