The road to Diakofto winds its way through forests of pine and down to the beaches lining the shores of the Gulf of Corinth. Across the gulf, Central Greece is visible with Mount Parnassos rising in the distance. The route narrows as it follows the north coast of the Peloponissos. The silvery-green olive trees alternate with the deep-green citrus groves, interrupted by the occasional picturesque village. To the left, the fertile plains and hill terraces of Achaia extend to the mountains of Arcadia. Our first stop is at Diakofto, about a two-hour drive from Athens, where we board the tiny train that goes to Mega Spileo, Kalavryta, and Aghia Lavra for a journey through centuries of Greek history.

In ancient times, the area was the seat of the Achaean League, a confederation of towns that banded together to protect themselves from invasion as early as the fourth century B.C. In the early days of the Christian Era, Achaia was converted to the new religion through the preachings of the Apostles Andrew and Paul. According to tradition, St. Andrew was crucified in Achaia. After the Frankish conquest of the Morea, the name by which the Peloponissos was known in medieval times (because of its shape which resembles that of a mulberry leaf — Morea means mulberry tree), the entire area was divided in 1204 into twelve fiefs which were allocated to various barons of France, Flanders and Burgundy. Later, the Byzantine Empire gradually regained the Morea and retained control until the Turkish invasion which began in 1458. Except for the interlude of 1687-1715 when it was conquered by the Venetians, the area remained under Ottoman rule until 1821.

one may visit Mega Spileo monastery.

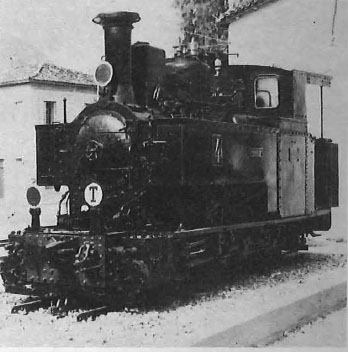

Diakofto is a sleepy little town with a single hotel overlooking the central square which is dominated by a railway station far out of proportion to the size of the town’s population of 2,500. Behind this modern station, which is on the Athens-Patras line, there is the narrow track along which runs the train which has brought Diakofto its fame. The construction of this little railway — a remarkable feat of engineering — was begun in 1889 by Italian engineers. At the time, it provided the only means of communication from the coast to Kalavryta and the surrounding mountain villages. (Today the area can be approached by a road from Platanos, a few kilometres from Diakofto.) Although the railway’s course is seemingly treacherous, there has never been an accident on the line, one of the oldest in the country. Folklore attributes this to the fact that it is under the protection of the Virgin Mary. Up until a decade or so ago, it ran on steam, and permanently installed near the station is the original engine bearing an inscription in French and the date 1889. The now-idle engine is still referred to as the karvouniaris (charcoal one) or moutzouris (the smudger) as the men working on it were always blackened by the smoke.

When the steam engine was still in use, the journey took two hours. The train moved so slowly it is said that passengers were able to get off as it moved, gather flowers, and climb back on. Today it runs on electricity. It begins its first run at eight in the morning and passengers can purchase tickets just before departure.

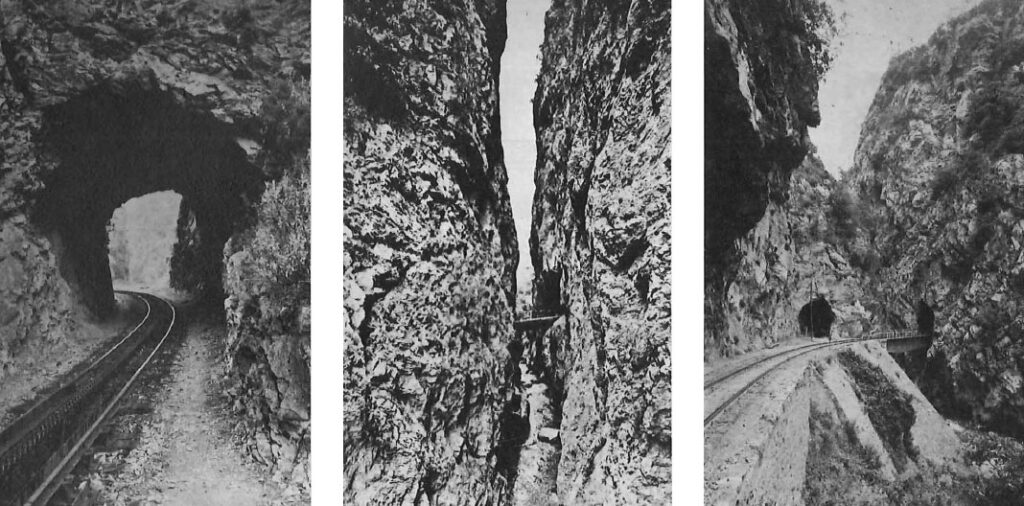

The engine is positioned between the two coaches, and pushes the one in front, and pulls the other from behind up the abrupt slopes along the Vouraikos River. Appearing first on the right and then on the left, the river rushes down from high up in the mountain, at some places like a waterfall, and at others flowing quietly over the rocks. The extraordinary, scenic route passes through seven short stone tunnels, their walls still black with soot from the earlier steam engines. As the train approaches the end of tunnels, sunlit trees, flowers, rocks and foaming waters reappear blindingly at the other end. At times the inclines are so abrupt that rocks and mountains seem to be suspended from above. As the train continues its laborious climb, the river becomes even more rapid, the incline sharper, and between the two regular rails a third notched rail appears. A special mechanism is lowered from beneath the train and hooks onto the large teeth of the middle rail helping to pull the train as the engine heaves its way up the final ascent.

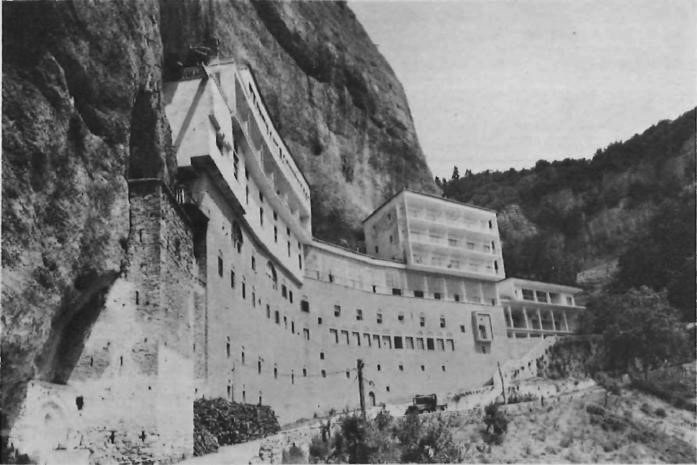

The first stop is at the tiny village of Zahlorou located on the thirteenth kilometre of the journey. From here one may visit the monastery of Mega Spileo — the Great Grotto. The village itself, consisting of a population of two hundred, with a pleasant, fourth-category hotel and several tavernas, extends across lush green slopes watered by the Vouraikos River which cuts through the centre of Zahlorou. From the station, it is approximately a one-hour climb (one may rent a donkey for the trip), up the zigzag path through a ravine, ‘The Spring of the Maiden’, and the monks’ garden which leads to the monastery of Mega Spileo. Located at an altitude of 924 metres on the beautiful slopes of the Aroania mountains, Mega Spileo is among the most notable monasteries of the Peloponissos. It stands seven or eight storeys high on massive foundations, and the entire structure is built into the side of a precipitous rock cliff.

Although today there are only a few monks in residence, Mega Spileo was one of the wealthiest monasteries in medieval times, with vast estates in the Peloponnisos and property in Constantinople, Salonica and Smyrna. Its library was well-stocked and its cellars used to house enormous barrels — with male and female names — which held as much as twenty thousand litres of wine. During the Ottoman period, the monastery was attacked twice by Turkish forces, but never captured. On one occasion the Ottomans attempted to sieze it by toppling an immense rock from above but, according to legend, whenever the rock reached the edge, it rolled back by itself forcing the Turks to abandon the task.

Another legend explains the monastery’s beginnings. During the fourth century, two monks, Simeon and Theodoros, travelling from Thessaloniki, were visited in their dreams by the Virgin Mary who urged them to go to the Peloponissos. There they came upon a young shepherdess of royal blood, Efrosini, who told them a strange story. One of her goats kept wandering off, returning with his beard wet. Curious, she followed the goat into a cave where the Virgin Mary spoke to her, telling her of the impending arrival of the monks. She led the monks to the cave where they found, among the rocks and wild plants, a holy icon of the Virgin. Today the miraculous icon, which is said to have been executed by St. Luke, is housed in the nearby church dedicated to Panagia Chrisospiliotisa — The Golden Virgin of the Grotto’.

Over the centuries, the monastery was besieged by many conflagrations and was particularly vulnerable to fires because the early buildings were largely constructed of wood, and because of the lack of water. (The church was always spared, however.) As a result, the monastery has been rebuilt many times and lost much of its original charm. But the superb setting, the panoramic view from the old watch tower above the rock, and the many relics within the monastery’s walls make a visit an unusual experience. The library contains many rare manuscripts. The mosaic floor, which has the two-headed Byzantine eagle, and the bronze door of the church are considered masterpieces. A particularly unusual icon represents the Virgin and Child with an elaborately dressed young boy, said to have been a member of the Palaeologus dynasty who died at a young age. The Palaeolous family furnished the last eight emperors of the Byzantine Empire, and branches of the family ruled the Morea from 1383 to 1460. The icon is very rare because it includes a portrait of a secular figure.

Reboarding the train in Zahlorou, the journey continues on to Kalavryta through less rugged terrain, traversing a plain scattered with charming, stone leantos for sheep, stopping next at Kerpini, a little settlement nestling on the slopes of the mountain. Kerpini is a corruption of the name of the French nobleman, Hugh de Lille de Charpigny who governed the area in Frankish times.

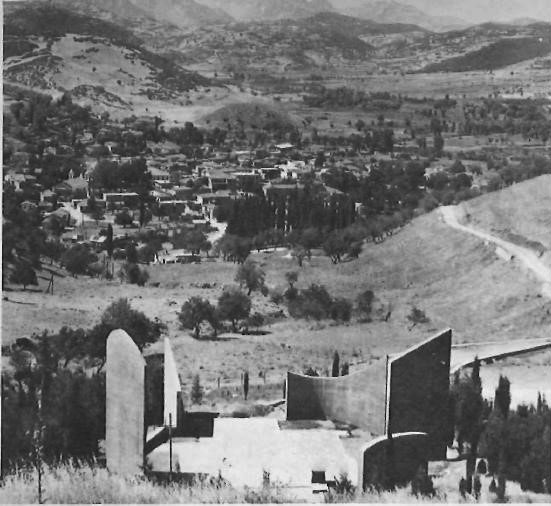

As the train continues to Kalavryta, the Vouraikos River disappears. Kalavryta means ‘Good Springs’. Situated at an altitude of seven hundred and fifty metres it is surrounded by mountains whose snow-covered summits rise to an altitude of over two thousand metres forming an imposing backdrop to the flower-covered pastures below. The houses of the town are spread out over a large area so that the first impression is that one has arrived at a small city. It is a lovely site and a pleasant summer resort, on the site of the ancient Arcadian city of Cynaetha.

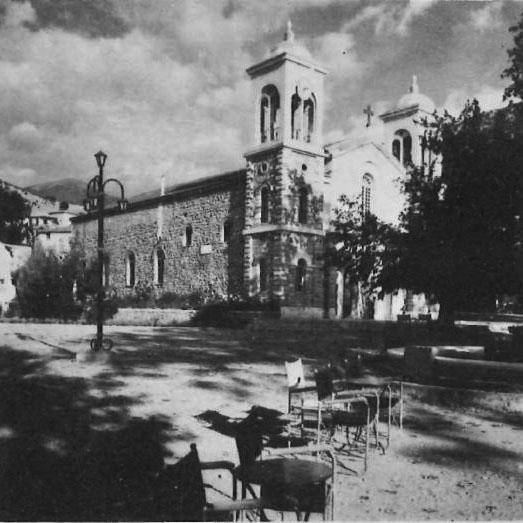

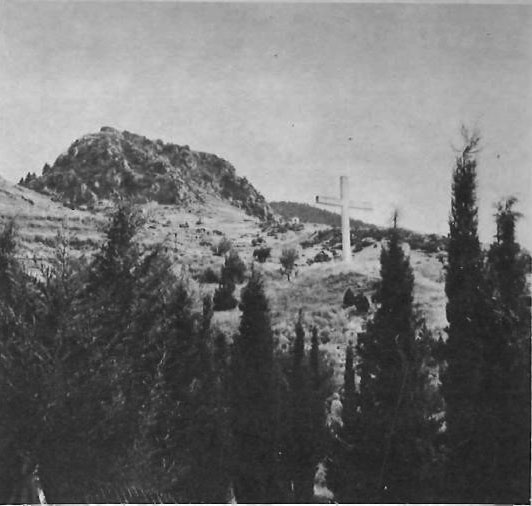

In the main square of the town is the Metropolis or Cathedral, restored after it was burned down in 1943. The hands of the clock on the bell tower are stopped at 2:34 and mark the hour of the massacre, on December 13, 1943, when more than fourteen hundred people — all the males over fifteen years of age — were massacred by the German occupying forces. The village was burned to the ground. A sign at the station directs the visitors to the slopes of a hill marked by an immense cross and an austerely simple monument. On the newly paved road that leads to this site, we encounter a middle-aged woman bent over the ground collecting wild greens. She straightens up as we approach and in reply to our queries says that people come from ‘everywhere in the world’ to visit the monument. She was a young girl at the time of the massacre. All the women and children were imprisoned in the schoolhouse which was set afire but the guardian, a young Austrian, took pity and released them. ‘What did we see? I hope that neither you nor anybody else in the world sees something like that again!’ she says, pulling her black kerchief down over her forehead, a shadow crossing her eyes.

structure.

On a rocky precipice near the village are the ruins of ‘Tremola’, a thirteenth century castle. The name comes from the Baron Humbert de la Tremouille, who succeeded Baron Otto de Tournai. The castle is also known as Kastro tis Orias, named after Katherine Paleologus who is said to have committed suicide in 1463 rather than be taken by the Turks. Back in the village one should sample the unusual local rose petal sweet, before reboarding the train and setting off for the seven-kilometre trip to the tenth-century monastery of Aghia Lavra.

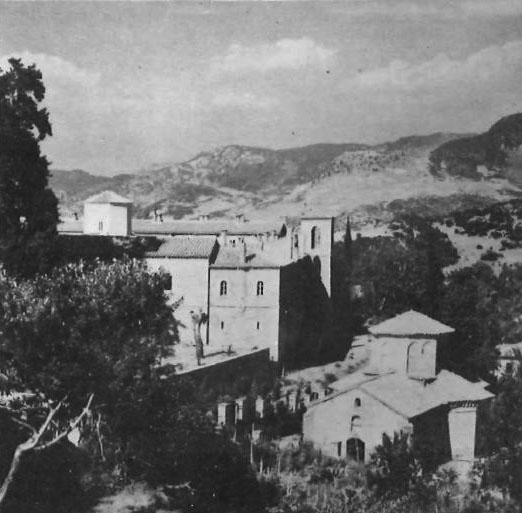

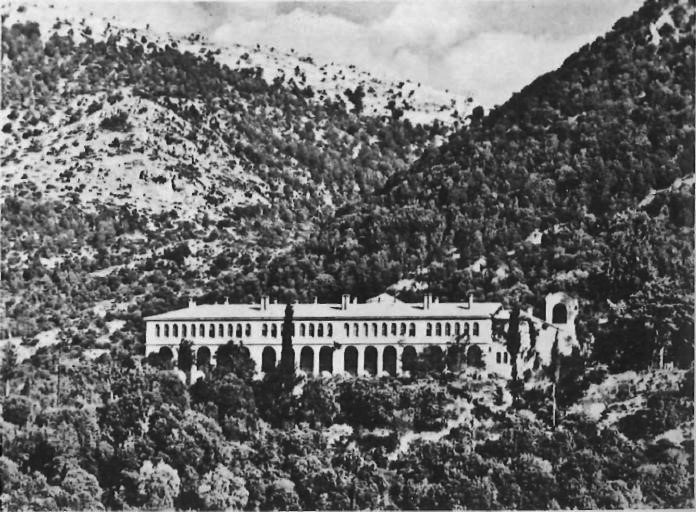

Aghia Lavra is set on top of an oak-covered hill, its cluster of red-tinged buildings seeming to touch the transparent sky. Aghia means holy when not applied to a person and lavra means intense heat. The monastery’s name, Aghia Lavra, refers to the passionate devotion of the monks’ dedication to God. Entering the large courtyard and following its paved road, we arrive at a beautiful little church where a young monk explains its history. The chapel, which stands nearby, partially constructed in the craggy rock, is on the spot where the first chapel was built in 961 A.D. by two monks. As the number of monks grew and the facilities became inadequate, they dispersed in small groups, living in little huts erected in the fields. Here they cultivated the land and made handicrafts, returning to the church only on weekends to receive the Holy Communion, sell their products, and take back food for the coming week. The original chapel was in later centuries destroyed by the Turkish invaders who dispersed the monks, the young monk tells us, crossing himself and turning his eyes toward heaven.

Within the church the walls are covered with frescos. It was here, according to popular history, that Germanos, the Bishop of Patras, met with other prominent clergy and laity and took an oath to fight for Greek independence. The icon-banner which they unfurled is preserved today, its richly-embroidered silk encrusted with gold and pearls that circle the Virgin’s head. After the revolution, a third church was built surrounded by large interior courtyards and rooms. The entire complex is in the form of the phoenix, the legendary bird which rises again from its own ashes. The museum houses treasures from the monastery’s long history and in its library are many rare books. A startlingly modern innovation is the tape-recorded guided tour in the museum, but it is very practical for those who understand Greek.

Historians do not agree with the popularly accepted interpretation of the events surrounding March 25, 1821. Some are of the belief that the motives of Bishop Germanos and those who met with him at Aghia Lavra were far less heroic than is generally believed. Other historians draw attention to the fact that the roots of the revolution can be traced further back to at least 1814 with the creation of the secret society of the ‘Filiki Eteria’. The site, nevertheless, will continue to stand as a symbol. When on March 25 dawn breaks over Athens and church bells peal throughout the nation, most citizens will be thinking of Aghia Lavra, and the group of men who are said to have gathered there one hundred and fifty-seven years ago to declare Greece’s independence from Ottoman rule.