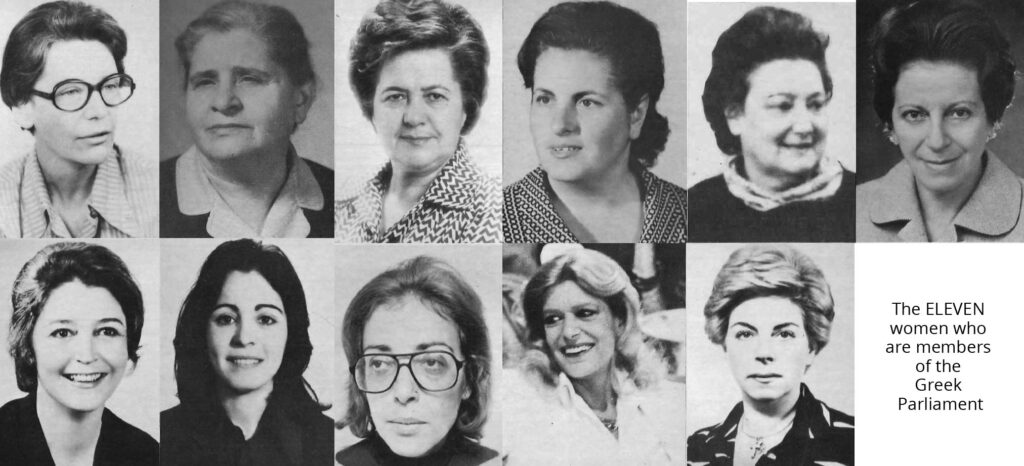

Anna Synodinou-Marinaki, one of the governing party’s three women deputies in Parliament, is the only woman in the Cabinet. As Deputy Minister of Social Welfare, she will now devote herself to the issues that were her major concerns when elected to her first term in Parliament in 1974. Ί know that my responsibilities are now greater,’ she notes, ‘but I believe we must all work with conviction. I have very good colleagues here at the Ministry who are helpful and with whom I feel at ease.’

A tall, imposing figure, Anna Synodinou studied at the National Theatre’s School of Drama and went on to become one of Greece’s foremost actresses. During her twenty-five years in the theatre, she has played a great variety of roles but gained international recognition for her performances in ancient drama. She recently appeared in Euripides’ Helen at the 1977 Athens and Epidaurus Festivals. Ί feel as though I have had the experience of a century-old man. Ι learned to smile and be patient. Now, when at the end of the day I look back and see it was not wasted, I am satisfied.’

Her new role in the cabinet will leave her with little time for the theatre, but she does not exclude appearances at the summer festivals. The theatre lies deep within me but I have more important work to do now for my country,’ she says. ‘Work is a source of vitality tome.’ She is concerned with the welfare of the entire nation, the human suffering, the ‘struggles of life’ throughout the country, not just in Athens, where she was elected. One of her primary concerns is to provide better care for children, Our hope for the future’. The United Nations has declared 1979 The International Year of the Child, and in July an international symposium will be held on ‘The Child in the World of Tomorrow’, organized by the Institute of Child Health. Among the sponsors will be the Ministry of Social Welfare. Meanwhile, the Undersecretary has cast an eye around the Ministry and plans some practical housecleaning: among the first things on her agenda is to replace the official black limousines (‘relics of the royal past’) with smaller, more economical vehicles. ‘It is not fair for us to arrive at the Ministry in them when others arrive wet from the rain,’ she observes.

The New Democracy’s selection of Aleka Mantzoulinou as one of its seven Deputies of State is a tribute to her many years of public service. The twelve Deputies of State in Parliament do not run in the elections, but are appointed by the parties on the basis ot distinguished accomplishments and represent the country as a whole rather than a particular constituency. Since 1948, when Mantzoulinou headed the Association of Greek University Women, her activities and interests have encompassed a wide field. Born in Istanbul, she came to Greece as a young child. She studied music at the National Conservatory from which she holds a diploma, and graduated in Law from the University of Athens. Her many activities have been widespread on both a national and international level. She was the first woman to sit on the Athens Municipal Council, and in 1956 was invited by the U.S. State Department to study governmental affairs and women in public life. Over a period of three months she visited eighteen states and twenty-three cities (among her souvenirs are the keys to three of them). She was a delegate to seven United Nations General Assemblies and Greece’s Representative on the Social, Humanitarian and Cultural Council. From 1962-73 she headed the International Law and Suffrage Committee of the International Council of Women, the largest federation of women’s organizations in the West, and from 1973-6 was Vice-President of the Council. She was Vice-President of the Greek Red Cross and President of the International Relations Committee of the International Red Cross Association, but resigned when she entered Parliament. She will continue as a member of the Commission set up by the Greek Ministry of Justice to review Family Law. Revisions in the Civil Code will be introduced, designed to bring the laws related to the family in line with the 1976 Constitution which granted equal rights to women. She is the mother of one daughter.

Julia Tsirimokou-Pimbli, the governing party’s third M.P., was elected from the district of Pthiotida, in Central Greece. She holds the distinction of being the only woman elected from the provinces. Rumor has it that this gregarious politician has kissed every voter in her region. As with many members of Parliament, she comes from a family long active in politics and is the daughter of former Prime Minister Elias Tsirimokos. Her ancestors have regularly represented her district since 1865. She speaks English, French and Italian fluently, having graduated from the School of Interpreters in Geneva where she also studied Political Science at the University of Geneva.

Ί have proven,’ she notes with undisguised satisfaction, ‘that there can be equality between men and women if you fight for it.’ Involvement in public affairs, she believes, should not be at the expense of the family. Married to the Prefect of Evia, she is the mother of two daughters. ‘Equality begins at the roots, during the early years of education. Mothers should treat their children the same way, regardless of sex’. She is particularly concerned with issues involving provincial areas. Ί would like to see the remote villages united to form small towns, to see factories distributed evenly all over the country and not concentrated around the highways’, she declares. Til open an office in Lamia and spend my weekends there with the people. I was sure I would be elected and now I’m going to work for the area which I love.’

The unexpected gains at the polls made by the Pan-Hellenic Socialist Movement (PASOK), which replaced the Centre Union (EDIK) as the major opposition party, swept five women into Parliament, among them two internationally known figures, Amalia Fleming, who is a Deputy of State, and Melina Mercouri, who was elected an M. P. from Piraeus.

Amalia Fleming was born in Istanbul, but grew up in Athens where she studied medicine. In 1946, she was awarded a British Council scholarship to continue her studies in London where she was to work as an assistant to Sir Alexander Fleming who, the previous year, had won the Nobel Prize in medicine for his contribution to the discovery of penicillin. They were married in 1953. Sir Alexander died in 1955, and Lady Fleming returned to Greece in 1961. She was imprisoned for her Resistance activities during World War II and again by the Junta which eventually exiled her. While living abroad she waged a relentless campaign against the dictatorship.

‘Ι’ll speak to you about women as human beings,’ she informed me when I called at her home. Although she was in bed recuperating from a mild case of influenza, her work continued. Surrounded by books, photographs, and memorabilia, she methodically answered calls and made appointments. Her small penthouse apartment in Kolonaki is bright, warm, and bursting with flowers and plants. Her well-nourished cats are curled up nearby. ‘The problems of women are part of the general problems of mankind,’ she observes. The difference between our party and the Right is one of priorities.’ Among the priorities she cited are social welfare reform. The old attitudes long instilled in women, particularly in rural areas, can be changed through education and there is a need as well for maternity benefits and child care centres. ‘There is no lack of money for all of these things. Money is only an excuse’, she notes. Meanwhile, she believes, the Greek woman must gain self-confidence. There were thirty-six women candidates in 1974, of whom seven were elected. In the November 1977 elections, there were one-hundred and three, and eleven were elected. That is progress, she observes, but not enough.

When I called Melina Mercouri for an appointment, the husky voice demanded to know why journalists look upon women politicians as guinea pigs or show horses. Nevertheless, she agreed to see me. Although best known for her work in the theatre and cinema, Melina Mercouri’s life has centred on politics. Her grandfather, Spyros Mercouris, was Mayor of Athens for forty years and her father, Stamatis, entered Parliament at a young age. ‘Politics has always been a part of my life. Cinema and theatre were where I earned my living’ she stated. Her wood panelled apartment is warm and comfortable, reflecting Mercouri’s interests and personality. With the exception of her latest, as yet unreleased film, which was shot last summer in Athens, she has in recent years done little work in films. A major reason for this, she explains, was that no international firm would insure her: because of her anti-junta activities, attempts had been made on her life in New York and in Genoa.

In the tradition of such figures as Winston Churchill who was known to have conducted affairs of state from his bed, Mercouri is swathed in a cloud of pink sheets. Her personality and charm are distracting. Ί believe in collective work,’ she stated. ‘I’m used to it from the theatre and cinema. The same is true of politics and we will work as a group. The fundamental structure of society should change. In capitalistic countries, society belongs to men. On the contrary, in socialistic societies men and women are equal.’ Although she has not abandoned the theatre, for the present she is completely dedicated to her new position as member of Parliament and to the needs of her Piraeus constituents. ‘I’m opening an office there to be as close as possible to the people who believe in me and voted for me.’

The three other PASOK parliamentarians all represent Athens: Constantina Yannopoulou, Irini Lambraki, and Maria Kypriotaki-Perraki. Deputy Kypriotaki, the oldest child in a family of daughters, explained that she was given the education of a boy. ‘When we had a discussion, my father didn’t expect me to agree with him if I didn’t wish to,’ she said. Born in Crete where her father was a priest, she studied medicine in Athens and is now a successful gynaecologist on the staff of a maternity clinic. ‘My patients begin by calling me Mrs. Kypriotaki, but we soon become friends and during delivery I’m always “Maria”.’

The mother of two children of whom she speaks with maternal pride, she administers to her patients and their families with a calm air and compassion. Although there are many women practicing medicine in Greece, she is one of the few in obstetrics and is highly respected professionally. ‘Because of my work and my involvement with many women’s organizations, I’ve always been close to women’s issues.’

Now that she is in Parliament, she feels she can make more concrete contributions. When I ask how she will manage to fulfill her responsibilities as wife, mother, doctor and parliamentarian, she replies without hesitation. Ί don’t know what fatigue means, because I have never known relaxation. I’ve worked hard since my student years. Some nights, when I have a difficult delivery case, I do not sleep at all. The possibilities of every human being are unlimited as long as one has the will and a program, in which case one can find the time and the means to accomplish everything.’ And, indeed, Dr. Kypriotaki is organizing her political office and focusing ‘on the implementation of social changes and the development of a just society.’ Her principal concerns are women, children, health and education.

Constantina Yannopoulou, a retired court employee, was a member of the National Liberation Front (EAM) and a Resistance fighter during the Occupation. During the dictatorship, her husband, Evangelos, who is today President of the Athens Lawyers’ Association, was imprisoned and exiled. She has two children. A founding member of the Union of Greek Women (EGE), she was not pleased with the way women voted in the last election. The fact that men and women vote at separate election centres provides an immediate breakdown of statistics as to how the sexes vote in Greece. Noting that three women running in Athens drew between them thirty-one votes at one women’s election centre, and twenty-eight at another, she expresses the view that women’s groups should study such results closely: ‘Men cannot understand our problems.’ She believes that women must fight for their rights. ‘We do not have a quarrel with men, but we constitute fifty-one percent of the population and must play a more important role in political life,’ she observes. Coping with her many responsibilities does not pose a problem. ‘To me the phrase “I cannot do that” does not exist. It is more honest to say, “I do not want to”.

When Irini Lambraki appeared at the polling station in Erithrea, the guard did not recognize her and ordered her to queue up. It took some moments to convince him that she was a candidate. But her youthful appearance belies the lawyer’s determination. She speaks quietly but with self-assurance. ‘To be honest, I didn’t expect to be elected. Many myths were abolished in the last election…old prejudices that women cannot work satisfactorily except in the house or in a small number of specialized areas have to be abolished.’ Born in Yannina, Deputy Lambraki studied Law in Athens, Literature and Art History in Italy, and did post-graduate work in Law in Germany. Women in Parliament must work particularly hard, she believes, in order to erase existing misconceptions and to inspire other women not only to participate in public life but to vote for women.

Lambraki’s campaign was low-keyed, the result of principles as well as economics. Although some candidates spent as much as thirty-five million drachmas on their campaigns, she was among those who had very little financial backing. Accompanied by several friends, she went around the city putting up her own campaign posters shortly before the elections. Returning to the subject of women’s rights, she notes that equality will not result from legislation only and reiterates the PASOK position that women’s issues must be seen within the context of society as a whole although, emphasizing the importance of education, she agrees that efforts must be made to bring them out of their isolation.

Virginia Tsouderou polled the highest number of votes within the Centre Union (EDIK), the party which suffered major set-backs and lost its place as the major opposition party. To her detractors, Tsouderou is stridently aggressive; to her admirers, she is simply a good politician who will not compromise with her principles. Born in Crete, she is the daughter of a former Prime Minister, Emmanuel Tsouderos. She studied Economics, Political Science and Philosophy at Oxford and Journalism in the United States. Her experience includes sojourns as an economist at the United Nations Relief and Rehabilitation Administration (UNRRA), the predecessor of the United Nations High Commission for Refugees, and as a journalist. During the junta she carried out a relentless struggle against the dictatorship and in recent years has been tirelessly active in many areas and participated in numerous international conferences. She is the mother of three children by her former marriage to the economist and banker George Gontikas.

Her office on Voukourestiou Street is well known since it was a centre for refugee assistance after the Cyprus invasion. Now it is staffed by an enthusiastic group of young people who address her as ‘Virginia’ . The walls are covered with photographs, a chart of the two-hundred and eighty questions she addressed to Parliament during the 1974-7 session, slogans such as ‘Women: Equal Opportunities’, a long poem about Crete, and a photograph of Eleftherios Venizelos, modern Greece’s foremost statesman and a compatriot. She arrives serene and fresh, her appearance revealing none of the stress and fatigue of the eighteen-hour day schedule she adhered to during the campaign. She attributes her victory to an acknowledgement by the voters of her work and principles. ‘The last election, regardless of the results, was the product of maturity. We are satisfied because we did not wish to profit from a vote of protest. Many politicians made errors because they were impatient. They did not put their ear to the ground to hear the voice of the people and listen to their wisdom.’ Even Venizelos, she notes, involved with the issues of World War I, lost touch. One is left with the distinct impression that Virginia Tsouderou runs no such risk.

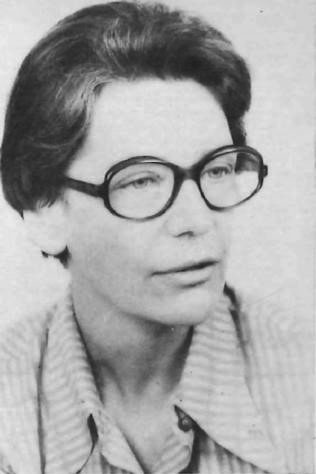

Legalized in 1974, the orthodox Communist Party of Greece (KKE) won approximately nine percent of the vote and has two women in Parliament, Nina Yannou and Maria Damanaki. (The Eurocommunists and Socialist Alliance, as well as the ultraright Rally party, have no women deputies.) Mrs. Yannou, who was returned to Parliament as a representative from Thessaloniki, is regarded as a highly able individual. She first entered Parliament in 1961 from a district in Athens on the ticket of the United Democratic Left (EDA). At her party’s headquarters, the esteem with which Nina Yannou is regarded is reflected in the profoundly respectful manner of her colleagues. She has now been chosen as the party’s parliamentary leader. A tiny, unpretentious woman, she is among the many Greek political dissenters, including composers Mikis Theodorakis and Yannis Xenakis, who carry permanent scars to remind them of their experiences. It is said that her eyesight is seriously impaired as a result of tortures and long imprisonments during the years of political repression that followed the Civil War (she was tried and found guilty by a military tribunal), and during the Junta. When I ask how she was able to endure the years of exile and persecution and keep her spirit intact, she replies simply: ‘Because I have faith in my ideals.’

Despite her quiet modesty, Yannou has a commanding personality and succinctly outlines her party’s views on domestic and international issues. She dismisses my question about the role of women saying, The problem of women and children cannot be separated from the problem of people in general, but motherhood should be recognized as a profession, one of women’s threefold roles which include the home and career.’ She notes the need to activate the potentiality of women, and the need for social policy that takes into consideration the development of the child, ‘the generation of tomorrow’. She herself has worked since the age of eighteen and is the mother of a son who is studying in Cologne, West Germany, on a scholarship from the Academy of the Federal Republic.

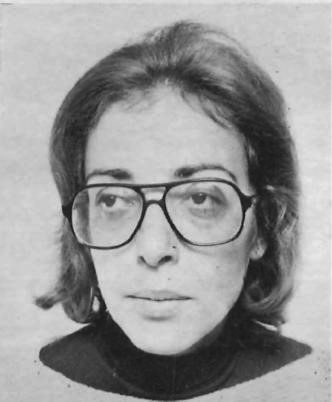

At the nearby offices of the Communist Youth of Greece, a sense of fraternity prevails as a bearded young man at the desk directs the comings and goings of an endless stream of young people. Maria Damanaki, at twenty-five the youngest member of Parliament, leads me to a large conference room with souvenirs from international meetings, and a library that includes the complete works of Lenin, a varied selection of Greek and foreign-language magazines, and other literature. Damanaki’s voice is well known to Greeks.

She was one of the announcers who broadcast from the radio station set up in 1973 by students at the Polytechnic Institute. During the fateful days before the dictatorship government sent in the tanks and invaded the Institute, the students appealed over the air waves to the nation for support and a return to democracy, their broadcasts beginning with the message, ‘This is the Polytechnic, the voice of the free students…’ Her goal today is the implementation of the party’s program as a whole, although she is deeply aware of the problems of youth and women in particular who must be ‘incorporated’ into the political and social life of the country. ‘We believe that the child should grow up in the natural environment of its family. Young children should not be allowed to work in factories.’ Furthermore, the fact that many students must work, in many instances full-time, in order to support themselves should be considered.

It is ironic that one of the leaders of the Polytechnic Uprising, which contributed to the fall of the Junta the following year, is the daughter of a career officer in the army and comes from a highly conservative family. Born in Crete, Damanaki has been an independent thinker since her schooldays, but it was not until she entered university that she became a political activist. A qualified chemical engineer who married a year ago, she will not work at her own profession as many MPs do, but will devote herself entirely to politics. She did not seek nomination, she notes: ‘The party decided for me and I simply accepted it.’

What emerged from the interviews with the women of Parliament was their deep commitment to social issues. Politicians traditionally pay lip service to such matters, but there was no mistaking the conviction of these women that welfare and education, issues that directly involve the individuals in a society, were of critical importance, and that Greek women, particularly, in the rural areas, must be brought out of their isolation to lead fuller lives and play a more active role in the political life of the Nation. Although differing in ideology, they have introduced a new dimension into Greece’s Parliament.