Photographs courtesy of the Photographic Archive af the Benaki Museum

One reason might be that since all these tools are handmade they can be classified as primitive art, an art which has almost disappeared with the advent of modern mass-produced hardware. Although some people, especially the private collectors who loaned much of the material for the exhibition, may feel this to be a paramount reason, and art critics will surely expound on the ‘functional beauty’ of the objects, it would be missing the point to view the entire show in those terms.

It has long been a cliche that man is a tool user and for all intents and purposes the only creature on earth who is. The very earliest artifacts of man found in excavations are his stone tools, familiar to everyone from museum displays. The careful study of a culture’s tools reveals a great deal about the society, its economic life, and its history. An archaeologist might conclude, for example, that since only one Neolithic village in a wide area contained large numbers of wood-working tools, the village was a carpentry centre whose products were diffused by barter.

Because tools are such common objects, it has always been assumed that ‘everybody knows about tools’. Perhaps this is the reason why so little can be found in literary sources about ancient and medieval technology. Why bother to write about something that everyone knew about? Furthermore, many Classical and Byzantine writers thought that writing about commonplace people and objects was beneath them. This has resulted in oddities such as the fact that almost all our information on the ancient pottery trade comes from the deductions of modern archaeologists and art historians because no ancient writer thought it a worthy subject.

The one hundred and fifty-four wood, iron, steel and stone implements exhibited at the Benaki were made locally from, perhaps, as early as the eighteenth century through the early twentieth century. Almost none of them are being made today in the same fashion. Many of them were rendered obsolete by the technological advances which transformed Greek agriculture after World War II. It should be remembered that agriculture was the main basis of the Greek economy throughout most of its history. Although art objects were a major export in Classical and Roman times, olives, vines and wheat were always the mainstay of the economy until the present day. The tools on display thus form a bridge with the past since their shapes and designs are virtually the same as those in use a thousand years ago and earlier. After all, a conservative peasantry is loath to change anything and since they were the ones making and using tools, the shapes became canonical. What was good enough for Grandfather was certainly good enough for Grandson.

The exhibition, organized by the Photographic Archive of the Benaki, will continue through March. It is found on the first two floors of the new wing of the Benaki (you enter through the Byzantine display area). A complete listing of the objects is available, in English and Greek, for ten drachmas. (Since the English listing is stapled together, it is wise to check that the last few pages have not fallen off.) A catalogue of the exhibit, in Greek only, should now be available. The display itself is very well done, the objects are generally well-lit on a black background. There are also numerous enlarged photographs of the tools in use by farmers at various times in the earlier part of the twentieth century, and, for comparison, photographs of similar scenes on Byzantine ivories. The only fault one can find with the display is that works are labeled with only numbers which refer back to the catalogue-list. This is an all too common custom of museum keepers who fear that long, informative labels will overwhelm a visitor: it results in the visitor leaving with many unanswered questions. A plus for the exhibit is the inclusion of very effective background music composed of old folk songs recorded by various ethnomusicologists. Unfortunately this music is thought to be of interest to only serious scholars and the Benaki was unable (they tried) to gain permission to sell recordings of the works. Nevertheless, the objects, the photographs and the display bring real life to the exhibit.

The ground floor contains implements relating to grains and olives. On the second are tools used for vines and for cotton. One of the main virtues of this arrangement is that it allows you to follow the entire cycle from planting through the final processing, showing all the implements used at each stage.

Wheat, in its final form as bread, is to the Mediterranean what rice is to Southern China. The populace of Rome was fed on wheat imported from Egypt, and Athens during its heyday received supplies from as far off as South Russia. While oil and wine were often exported and poor olive or grape harvests were unfortunate, a poor wheat harvest meant famine.

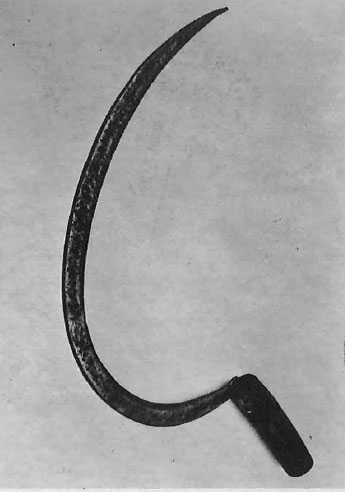

Prior to sowing, the ground was ploughed with the age-old wooden plough (aletri) or an iron one, first used in the nineteenth century. The soil was broken into large clods of earth which were further broken down by the harrow (svarna) into the soft earth suitable for sowing. When the wheat was ready for harvesting, the wheat stalks would be cut by hand with a large sickle (drepani). It is interesting to note that scythes do not seem to have been favoured. If the wheat stalks were shorter than normal, a special sickle (leleki) with a long neck was used. The reaper protected his fingers with wooden gloves (plamaria) or thimbles (dactilithra). These were equipped with long hooks which enabled the user to gather more wheat stalks and averted the possibility of the occasional finger being sliced off in a moment of inattention., The first sheaf of the harvest was set aside as an ornamental offering to be placed in the village church or in a family shrine. It would not be surprising if those sheaves (founta) Were of the same design as those offered to the goddess Demeter thousands of years ago. After the wheat was reaped it was bound up into large sheaves and allowed to dry before threshing.

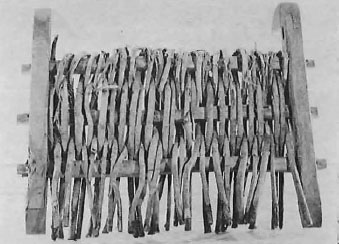

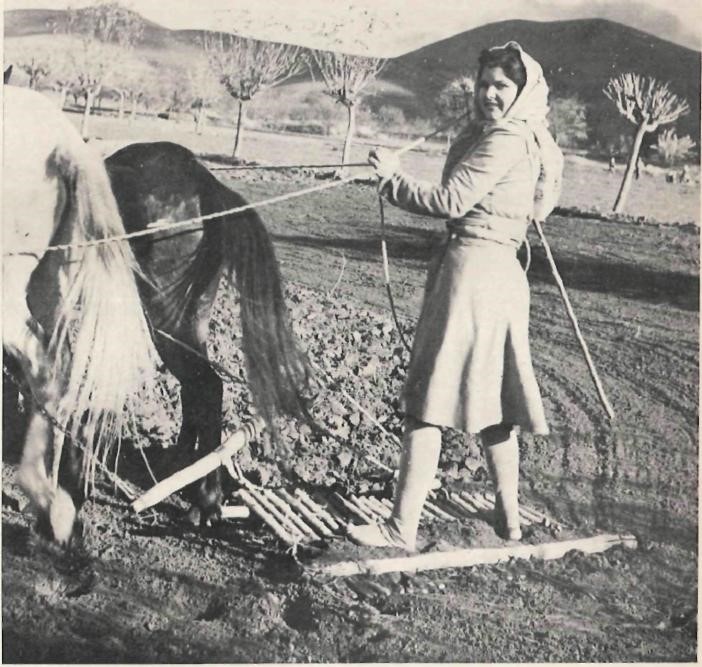

There were two basic ways to begin the threshing process: the wheat stalks were flailed (using a liradi) to separate the wheat grains from the stalk, or a special sledge (adokana) was dragged over the wheat. The former must have been quite a laborious process and, perhaps, was only used for smaller amounts of grain. The sledge would be drawn by horses with a person standing or sitting on it, simultaneously weighing it down and directing the team. These sledges were studded with metal and/or flint to break up the grain below. They are extremely archaic in design and similar to those dating back to Neolithic times. In fact, some of the flints on these modern examples are certainly ancient ones that were reused by the farmers who found them.

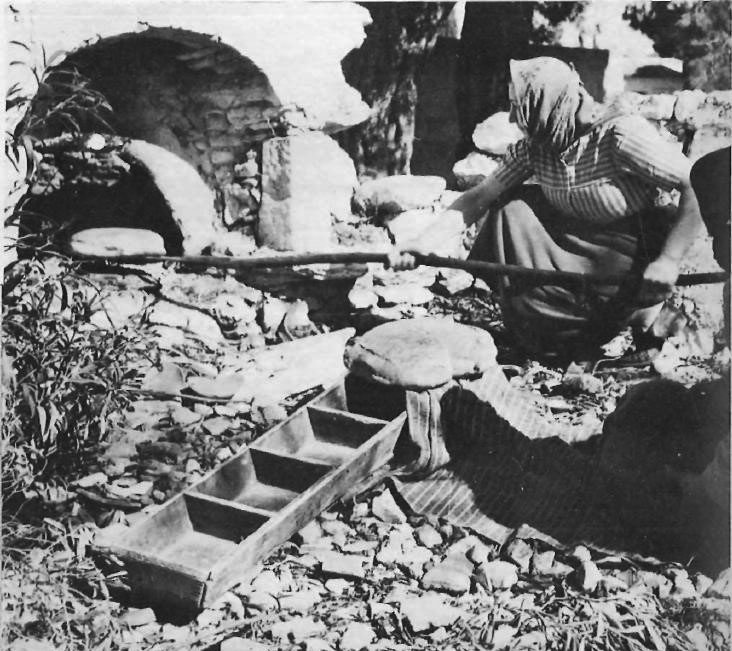

Once the threshing was finished the grain and the chaff were separated: the largest bits of stalk were removed with large pitchforks (dikrania with two prongs, thrinakia with three); smaller bits were removed with karpoloi (which resemble table forks) or wooden shovels called xiloftiaroi. Since wheat grains are heavier than the chaff, most of the impurities would be removed simply by tossing the mixture into the air and letting the wind blow away the chaff. The specialized tools would thus produce a pile of fairly pure wheat and lots of straw and chaff. A rake (ktena) was used to gather up the straw for use as animal feed. Sieves (remonia) would give the grain a final cleaning before it was measured and stored, The grain was ground into flour either commercially (in a windmill, anemomilo, for example) or at home (using a goudi or mortar or with a stone hand mill, cheiromilos). The flour was then kneaded in a special trough (skafi) which had its own special scrapers for cleaning (xystra), shaped on a board (plastiri), and then placed to rise in the hollows of a special board called a pinakoti. All these containers helped to prevent the dough from becoming soiled. Finally, long, flat shovels (ftiaria) were used to slide the risen dough into a wood-burning oven and to remove the bread when baked. Those without permanent ovens (shepherds and bandits, for example) used a terracotta contrivance (castra) which allowed bread to be baked over an open fire. This is similar to the method found in Europe and Asia, of cooking chicken encased in clay.

When visiting the exhibit, try to visualize the use of each artifact on display. All these tools had specific uses (such as the differing pitchfork types used in the winnowing process) and you can amuse yourself trying to figure out what they might be without using your catalogue-list. Antique collectors will certainly be fascinated by the objects on display and’ if you have a friend who is a collector of such items, you may finally be able to discover what it is he collects.

If nothing else, these old tools and methods demonstrate the extent to which mechanization has revolutionized the countryside: simple implements used from earliest times have been swept away by the twentieth century, never to be seen again outside of a museum. This has the corollary that the society which produced them, a society viewed with great nostalgia by those who did not live in it, has also vanished, and the effects of this disappearance are still being felt.