On August 26, 1923, Italian General Enrico Tellini and four of his aides were assassinated within Greek territory on the Greek-Albanian border not far from Ioannina. They were members of an international commission sent to delimit the Graeco-Albanian frontiers, a task that had been deferred since 1913 when the modern state of Albania was founded. The assassins were never identified. Historian James Barros who has exhaustively researched the subject, suggests that the murders were committed by roving bands of brigands, a reasonable interpretation, he notes, if one keeps in mind the history of the area during the period. The Italian Minister, Giulio Cesare Montagna, Italy’s diplomatic representative in Greece, promptly accused the Greek government of subsidizing the armed bands and of complicity in the murders. To this day, however, no evidence has ever been brought to light to support this contention.

Mussolini received news of the murders from his consulate in Ioannina on the evening of August 27. The Tellini murder had provided the Duce with his first opportunity to exhibit the ‘new diplomacy’ of his fledgling regime which had come to power in 1922. Although the Italians had emerged from World War I on the side of the victors, their failure to secure territories promised by the Allies in the 1915 secret Treaty of London had left them embittered. The expansionist policies of Mussolini’s fascist government had been thwarted by the League of Nations. Dominated by France and Britain, the League sought to maintain the status quo as established by the Paris Peace Treaties. Mussolini’s foreign policy had as its main tenet the revision of the borders set by the Treaties. His wider purpose was to eventually reestablish the Roman Empire; he thought of fascist Italy as heir to the ancient empire as well as to medieval Venice. These concepts validated Italy’s right, according to Mussolini, to dominate the Mediterranean. The eventual invasion of Ethiopia in 1936, the seizure of Albania in 1939, and the unprovoked attack against Greece in 1940 were all steps towards the fulfillment of his goals.

Thus, in response to the Tellini murder, Mussolini dispatched through Montagna a list of demands to the Greek government with a speed rare in the annals of diplomacy. The demands included an apology from the ranking Greek military officer; a funeral service for the victims to be held in the Roman Catholic Church in Athens, and to be attended by all members of the Greek government; an investigation to be completed within five days of the arrival of an Italian military attache sent to aid in the investigation; capital punishment for the assassins when found; a sum of fifty million lira indemnity to be paid within five days; honours to be paid to the Italian flag. The message contained no threat against the island of Corfu, and neither the Greek government, nor the British and French, interpreted it as such. The British and the French, fearful of a conflict between Italy and Greece, were of the conviction that all actions should be taken within the framework of an international organ, particularly since the Tellini mission had been conducted under the aegis of the Conference of Ambassadors in Paris. Diplomatic exchanges got underway between Greece, Italy, Britain and France, with the latter stressing collective action.

In Greece, a cabinet meeting was immediately called. The Prime Minister, Stylianos Gonatas, subsequently issued a statement saying that Greece was prepared to meet some of the demands since the murders had taken place on Greek soil. On the evening of August 30, within the time limit set by the Italian dispatch, the Greek government replied to the Italian government, refuting the Italian allegations that the Greek government was guilty of complicity, but agreeing to extend an apology, to the stipulated funeral, and to the military honours. The other demands were rejected or modified.

Within hours after receiving this response, Mussolini ordered the Italian navy to attack and occupy the island of Corfu. Among the witnesses to the bombardment of the island were John Henry House, the founder of the American Farm School in Thessaloniki, and his wife, Susan Adeline House. Mrs. House’s unpublished correspondence provides an account of the episode:

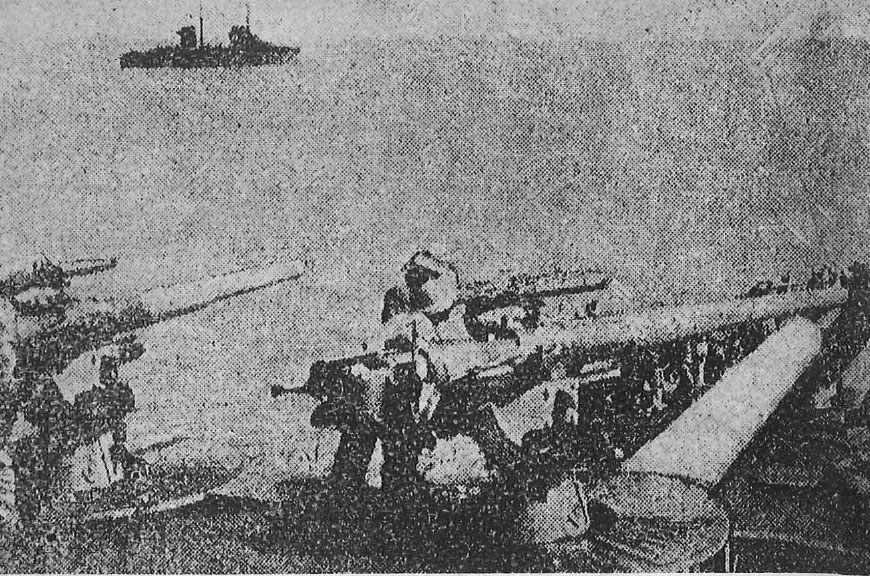

Noon of that day we heard that an Italian fleet was entering the harbour, and when we went to watch the arrival, we found there twelve ships, four of them battleships, and that the decks were cleared for action. We thought it was nothing more than an attempt to frighten the authorities as the island is not fortified. When the English turned it over to the Greeks, it was with the understanding that the Citadel should be dismantled… When the airplanes began to circle around us… they came so close that the noise was almost deafening. There were two very heavy shots that we could not mistake and which sounded like machine gun fire. We heard the screaming women and children as they fled from the citadel.

The island was undefended. As a result of the bombardment, sixteen people were killed and scores wounded. The bulk of the victims were refugees, still displaced from World War I, many of them orphans sheltered in the old Citadel, built by the Venetians. The attack was to raise an international outcry.

Mrs. House relates the quick surrender of the island:

There is a small place where the top of the citadel can be seen from some of the hotel windows and when a white flag was seen flying there we were quite sure what had happened, even before the word was brought to us that the island was no longer Greek but Italian. We went out for a walk about six o’clock and saw the white flag hauled down and the Italian flag run up.

Corfu had been taken. The Greek government immediately appealed to the League of Nations, declaring its willingness to abide by any decision. Public opinion, particularly among small nations, was outraged. It was obvious that the League was confronted with a test case which demanded quick and firm action. The League met two days after the invasion to debate the matter but finally referred it to the Conference of Ambassadors. The Italian delegate maintained throughout the debates that the League was not competent to act on the matter and Mussolini threatened to resign from the world body. Mussolini had clearly breached the covenant of the League of Nations, according to which it was within the League’s authority to deal with the case since the matter threatened world peace, and, furthermore, the incident involved two of its members committed to settle their disputes peacefully.

The League of Nations differed from earlier international organizations in that it provided for collective security. It did appear to be a more positive instrument than the pre-war groupings which were held together by a system of alliances so convoluted that it had been one of the causes of World War, I. The guaranteed territorial integrity and the independence of all members, and Article 12 in particular by which all members agreed to submit disputes to arbitration or to inquiry by the League and not resort to war until three months after a report was rendered, were both promising features.

The Corfu incident thus became a crisis in European relations. The situation between Italy and many of the members of the League was greatly strained. Britain’s attitude towards the Italian dictator had become hostile, since it had long considered its dominant position in the Mediterranean to be a main foreign policy objective and the Italian aggression against Corfu was without doubt a direct threat to British hegemony.

The League persevered for a solution to the Corfu crisis and drew up a plan of settlement which it forwarded to the Conference of Ambassadors. Italy was granted a fifty million lira indemnity. The concentration of the British fleet within sight of Corfu helped persuade the Duce to abide by the adjudication. By September 27, the Italian forces were withdrawn, one month to the day of the Tellini murder.

Historians evaluate the first test case of the League with varying opinions. Some regard its outcome as a success since the Italian forces were withdrawn and Mussolini’s expansionism was temporarily forestalled. On the other hand, there is much to criticize in the quality of justice meted out: the League did not have the power to control the demands of the Conference of Ambassadors and it would be difficult to praise a solution according to which the victim of an invasion was made to pay the fine.

It was Mussolini’s first defeat. A few months after the incident, in a speech to the Italian senate, he stated: ‘In my opinion, the Corfu episode is of the very greatest importance to the history of Italy, because it has put the problem of the League of Nations before public opinion in Italy in a way in which no number of books could have done. Italians have never been much interested in the League of Nations; they believed that it was a lifeless academic organization of no importance.’

Historian Rene Albrecht-Carrie was to observe that ‘on fundamental issues of vital interest Mussolini would brook no interference from the League’. (Indeed, he withdrew from the organization in 1937 after the League approved sanctions against Italy.)

From 1923 onward, Mussolini subjected Greece to a series of harassment and provocations. Less than twenty years later, on October 28, 1940, Italy invaded Greece. Mussolini was convinced that Greece would quickly capitulate, but this was not the case. Within a few days, the Italian forces were driven back into Albania. Long before that, the League of Nations, in which countries such as Greece had placed so much hope, had collapsed under the weight of repeated Axis aggressions. On April 8, 1941, Germany attacked Greece. By May of that year the country had fallen. The Occupation had begun.