Sudan is the largest country in Africa but only a small part of its area, which ranges from barren desert to tropical rain forest, is habitable or productive. Until four or five years ago Kadugli was simply another town in Kordofan Province. When the province was divided into North and South Kordofan to make it more manageable, Kadugli became the capital of the South. Consequently, a fair amount of development, such as a textile mill, and various agricultural projects have been started. Kadugli has a population of some twenty-six thousand people, but draws on the inhabitants of the surrounding villages who buy and sell in the town’s market — the suk. During the autumn when the rains make the roads impassable, the shelves of the shops — square and brick-built — in the main suk are bare of everything but essentials. With the arrival of summer, they overflow with goods, from Chinese canned peaches to Woodward’s Gripe Water (beware of imitations). The smaller, outer suk of thatch and mud, has a more aboriginal flavour with its rows of women selling fruits and vegetables, its cobblers and its tinsmiths — who use every piece of metal they find, to make everything conceivable, turning tin cans into suitcases, coffee pots, charcoal stoves. ‘Tin Can Technology’ it would be called anywhere else.

As with many places like Kadugli, the transition from village to town is not complete. While one area is brightly lit at night, filled with the thump of generators, another will be suffused with shadows and the yellow light of oil lamps; where one woman draws water from a tap, another must fetch and carry from a nearby well.

In the evenings, the heat of the afternoon wanes and the shopkeepers return to open their stores. Sometimes I walk into town and sit at one of the outdoor cafes. Next to the cafe or beside the road, men squatting on grass mats laid out in front of shops perform the ritual before-prayer ablution. Their personal hygiene is immaculate. The average Muslim prays five times a day and must wash himself each time.

Three miles east of the town on the edge of a vast plain bordered in the stretching distance by more hills is the boys’ school where I teach English and where I live with my wife, Jil. In August, the area is overwhelmingly fertile and the rains turn the roads into thick, rich mud which one day’s sunshine bakes rock hard.

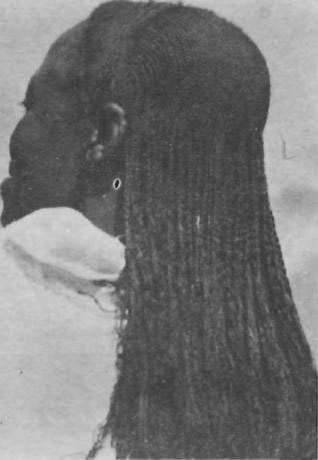

Children begin their schooling in Sudan at about the age of seven. The educational system is divided into three levels: Elementary, General Secondary and Higher Secondary. The teaching language throughout is Arabic but in the first year of General Secondary, English is introduced as a second language. Most villages have an Elementary Nuba women carrying home purchases made at the local market four kilometres away.

General Secondary school. There are three Higher Secondary schools in South Kordofan: two boys’ schools and a girls’ school where my wife teaches.

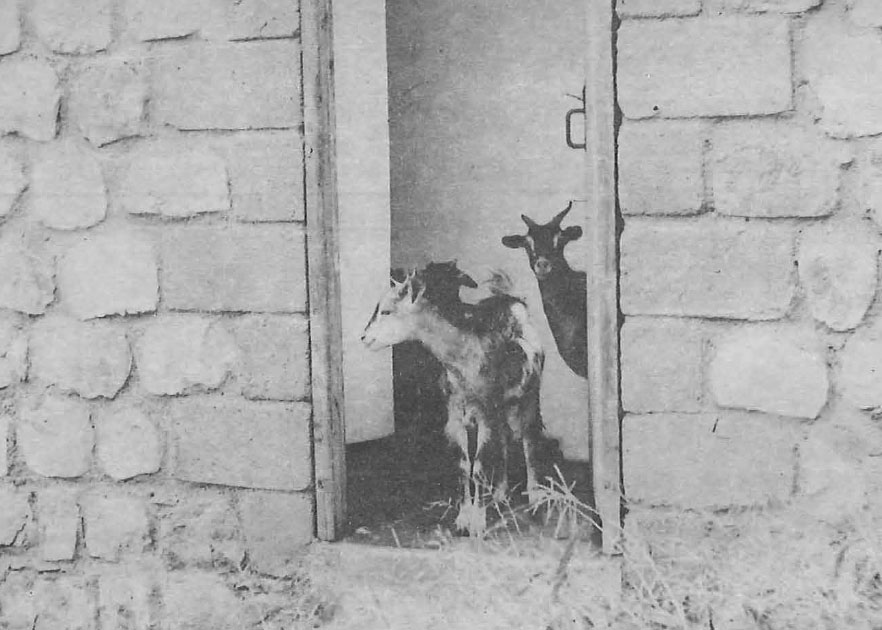

The school is surrounded by thatch and mud huts whose tops peek out from the centre of sorghum fields and maize patches. To the north, rising tangibly close, is a huge rock-faced mountain whose sides have shed the thin coverings of soil and grass. As I sit at school I can see it humped and boulder-strewn in the sun behind the classrooms. Over these hills violent storms, brewed in the spaces beyond, come crashing towards the town and all life cowers as great tumblerfuls of drops beat down. But they are expected and everything is cleared away. Children gather inside, goats pack together in enclosures or huddle beneath trees. Once, during a fierce storm, fifteen goats sought refuge in our outdoor lavatory. Milling around behind the door, they managed to push it shut. I had some difficulty explaining to the irate owner that I was not a great white goat rustler.

But the storms gather and vanish in two hours and life unbends, trucks get stuck and tractors and ropes are sought. It is a slow, exhilarating, ludicrous world where most things are accomplished tomorrow— ‘bukra, bukra ‘(tomorrow, tomorrow). Everywhere there are lunatic fat goats having their full udders bashed and sucked by thick-legged goatlings; donkeys hang their heads and moan in despair at their burdensome fate; indolent herds of cattle saunter past, occasionally emitting all-knowing groans from the centre of their six bellies.

Slowly I am becoming accustomed to teaching. The moment of first encounter is thankfully over: a skinny, white man, beard awry, legs feeling as useless as moulded cow dung, standing before a class of sixty Arab and African students. Jil and I are the only Europeans in the town besides a Catholic priest and some nuns who speak Arabic and Italian. The main problem is my accent. The students are not used to hearing English from the mouth of an Anglophone. At first there was total impenetrability, I thought. But, now I’m beginning to get the feel of it.

The Sudan is divided into two political areas, North and South. The seventeen-year civil war ended in 1971 but the friction between the Arabic North and the African South can still be felt, although efforts are made to give an appearance of unity. Into this fit the Nuba, the indigenous people of these mountains. During the civil war they fought on the side of the North, though they are Negroid people, and therefore closer racially to the Southerners. Now, the Southerners eye them with suspicion and the Northerners look upon them as Southerners.

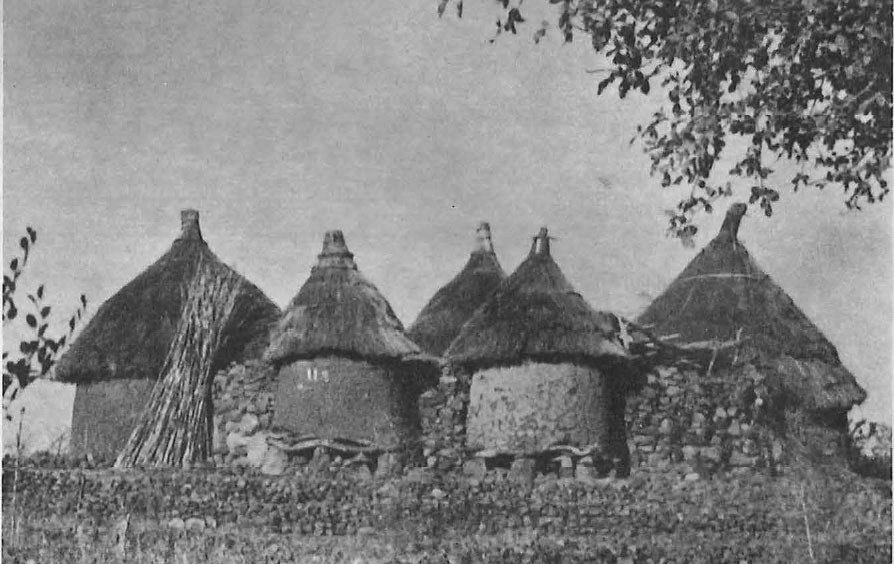

The Nuba are a small group of people living in isolated tribes scattered throughout the mountains. Outside the major towns their lifestyle has changed very little, but for those living around Kadugli it is altering; children attend school and adults work in jobs other than farming. They have a saying about themselves and their region: ‘ninety-nine hills and ninety-nine peoples’, which is some indication of their diversity. A diligent linguist has, however, pointed out that there are in fact eighty-seven languages. (And, one colonial administrator, Lt. McNeill, noted that there were considerably more than ninety-nine hills while compiling his topography of the region in 1914.) The fact that all these people speaking totally different languages should give themselves one generic term, ‘Nuba’, mercifully remains an enigma.

Traditionally they are sedentary farmers whose crops consist mainly of sorghum, nuts, some maize and a few vegetables. There is a good deal of underground water, but they practise primarily rainfall agriculture. Until twenty years ago, this area had two rainy seasons a year, the first falling in February or March and the second beginning at the end of May and lasting to the end of October. Now there is only the second. The effect on farming is difficult to ascertain. It makes little difference to the sorghum and corn but seems to have affected the vegetables and fruit which, because of the heat and dryness, are scarce by mid-summer.

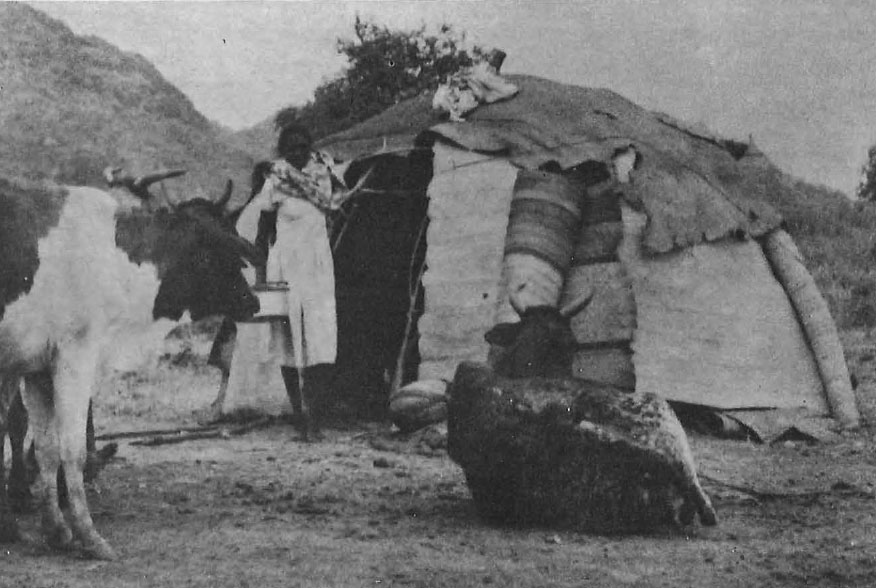

The other major group of rural folk in the area are the Baggara Arabs, cattle-keeping nomads who move with the seasons from the north to the south. Kadugli is the summer residence of a group called the Hawazima Baggara. Many of them have settled in the area; their sons attend school (and sometimes their daughters), they work in town as waiters, messengers and occasionally as drivers. Their herds dwindle and the old men sit in the evenings and listen to each other talk of the past.

Kadugli’s merchants are an assortment of ‘northern Arabs’, Syrians, Egyptians, Sudanese, Greek Sudanese, and the occasional Nuba. A cloth merchant named Makram is originally from Egypt. Jil once came upon him sitting glumly outside his shop, his spindle legs protruding from enormous, tailor-made shorts, and asked why he was depressed.

‘I’m forty-five years old. I have worked in this shop since a boy. Next week I must go to Khartoum, the capital, for ten days.’ At this point his eyes darted about his head, his thin fingers tearing through his hair in desperation.

Ί have worked so hard I never got time to marry. Now I have no son to look after the shop when I go. All this material just sitting!’ His hand swept over the packed shelves of cloth, his teeth chewing his lips. He later told us he was going to Alexandria at the end of the year to get a wife.

One Friday, the official day of rest, we decided to hire donkeys and go riding in the surrounding hills. When the owner arrived — several hours late for our appointment — one of the animals was lame. We left it with the owner and I mounted the other beast and rode it out of town amidst yells of encouragement.

I have yet to fathom whether the praise was for my success at mounting the animal (which bolted just as I was climbing into the saddle) or at the fact that I was, faithful to local custom, making my wife walk. I did notice on returning with Jil in the saddle that the elders of the town, chatting among themselves, disdained to acknowledge our return.

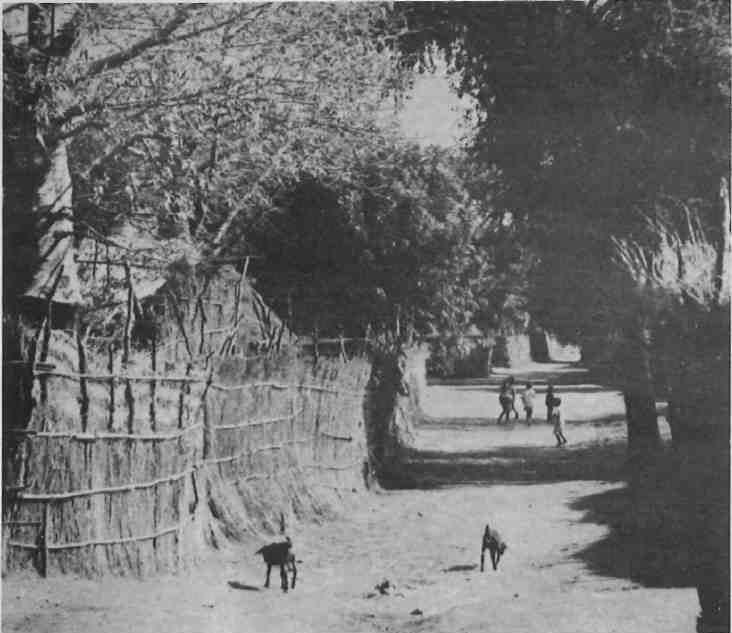

Riding a donkey is a euphoric experience and the best way to meet people. The pace is leisurely and, apart from the occasional attempt by the four-footed thing to dash in the general direction of ‘home’, the animal was quite passive. We headed west out of town through one of the surrounding ‘suburbs’, a village of clear-swept courtyards, thatch and mud houses and grass fences. Large trees enclose the homes in shade and the occasional date tree rises up like some totem of natural law amidst the buildings. Along the way people stopped to comment on the novelty of a ‘Khawaja'(European) on a donkey or just to chat and invite us to drink water. Fetched from great distances, this is a generous offering. There are three things which are never refused anyone: water, fire and food, a measure of how elemental their lives are. Yet this simple compassionate life is easy to callously romanticize. Their lives are hard and tenuous, stretched across the land, at times desperate.

Once the rains have finished it is possible to travel by lorry in this area. The students exploit this to the full, planning picnics and outings under the guise of the various school societies. The first picnic we went on was with about a hundred girls from Jil’s school. A bus and lorry were hired for the occasion. Hundreds of packets of tea were bought ahead of time, pounds of sugar, sacks of potatoes, loaves and loaves of bread, boxes of tomatoes and other foodstuffs, and three sheep which were tied outside the classroom until the day arrived.

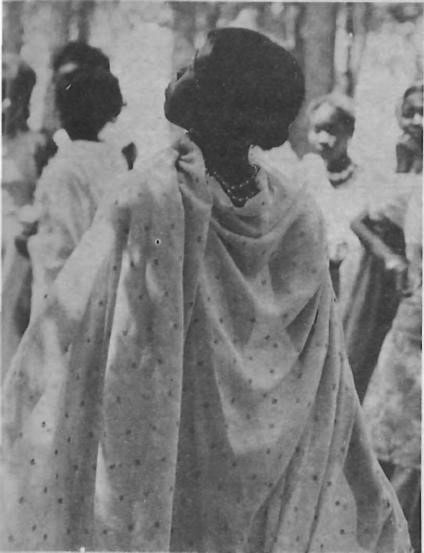

We were told to be ready at six o’clock on Friday morning. The picnic was to take place at El Dondoor, a forest about three hours journey away. At nine o’clock two crowded vehicles of ululating girls, between the ages of seventeen and twenty-two, swept up to us. They were dressed in all their finery: elaborate wigs, jewelry, perfume and colourful ‘tobs’ — the long flowing cloths which are draped around the body in a fashion similar to the Indian sari.

The journey was hectic. The girls in the bus were safe but those on the back of the open lorry faced some difficulties especially with their black, nylon wigs teased and curled high above their crania. As we entered the forest, one of the girls, swept away with the excitement, stood up and an overhanging branch whipped off her headgear. Howls of mirth and derision promptly brought the lorry to a halt and, while one of the driver’s assistants ran back for the wig, the young lady cowered behind her tob.

At the picnic site, the girls formed into groups and were assigned various tasks: collecting firewood, preparing breakfast or lunch. The dazed sheep were led from the back of the lorry and their throats cut with scant ceremony. The carcasses were hung from a branch and skinned. The girls, assisted by one of the drivers, proceeded to cut up the animals. At this stage I began to wish some developed nation, as part of its foreign aid program, would send out a couple of ‘experts’ to teach the art of butchery. Within twenty minutes, aided by an axe and some knives, they had reduced the three carcasses to a sodden mass of shattered bone and pulverized meat. Nevertheless, the food was good and plentiful.

During a three-week holiday in January, we decided to make the fifteen-hundred-kilometre journey to Port Sudan on the Red Sea. Travelling by road and rail is not something to be taken lightly. The distances are vast and transportation erratic, but we set off lighthearted and oblivious. The first leg of the journey was by lorry, with Jil sitting up front in the cab while I rode on the back, perched atop sacks of sesame. Hooting some bars from an unrecognizable melody, the lorry lurched out of Kadugli but stopped frequently at villages along the way to pick up more passengers although we were overloaded when we left. All along the route there were square, thatched buildings, roadside cafes with lorries parked outside and men, sitting on mats or wooden frame couches strung with grass rope, discussing the road. During the entire journey, we never so much as paid for a cup of tea. As foreigners, we were treated with the customary courtesy accorded to guests.

Meals usually consist of various combinations of broadbeans or lentils mixed with either cheese or tomatoes and onions spread with oil, a meat and vegetable stew, shish kebab, salad and sometimes sausage or kufta (mince meat). The food is placed in large bowls on the floor around which everyone gathers. I have grown accustomed to the practise of using only the fingers of the right hand to eat. The use of the left hand, reserved for other purposes, is contrary to the local laws of hygiene. In the beginning! had to sit on my left hand to remind myself not to use it and kept dropping food on neighbours and in other dishes.

At two in the morning we stopped for a few hours, and I collapsed into welcome sleep on the soft desert sand. Before sunrise we were heading east across the semi-desert plain, the lorry occasionally sinking up to its axles in the soft sand and having to be dug out. Twenty hours after we had set off, we arrived at Kosti, a large town on the White Nile. My hands were like claws from hanging on to the side of the lorry to keep from being thrown as it bucked over atrocious roads.

Kosti is a sprawling, untidy town, larger than Kadugli, and more Arabic, its mud houses square, with low, flat roofs that spread back from the Nile to merge with the desert. In the days of Lord Kitchener, Earl Kitchener of Khartoum, a Greek called Kosti operated a bakery in a small village beside the Nile. The fame of his baking spread and people travelled miles to buy his bread. I’m going to Kosti,’ they would say. The name stuck as the village spread out. The only bridge spanning the White Nile between Khartoum in the north and Juba in the far south, is located here. The people in the area say that the bridge was built in India during the British Presence and shipped to the Sudan. Whatever, it is an awesome expanse of steel girders and cement pillars. A railway line runs down the centre; there is a car track on each side, one of which has been closed for the past two or three years. Nobody seems to know why. At each end of the open side a policeman is posted to regulate the flow of traffic. At times it takes up to three hours to get to the other side in a car, particularly in the evening when cattle are being herded across.

After a short stay in Kosti, we boarded another lorry to take us to Sennar on the Blue Nile. Here we caught a train for Port Sudan. The vouchers issued to all teachers enable us to travel for a quarter of the normal price. We bought first class tickets and during the journey were served English meals in the diner by old silent waiters who dimly remembered the visits of thirsty governor-generals and portly queens. First class seats, however, had all been reserved, we learned before leaving, so we arrived at the station early, found seats in third class, and waited for the train to leave. Within half an hour our carriage and all others were full; boxes, sacks, and old, battered cases were piled between seats and in the aisle — trapping everyone in their places. It is not uncommon for people to pay third or fourth class fares and to ride on the roof which is not as dangerous as it may sound: the train runs too slowly. It stops at each station and is immediately surrounded by tea sellers, cool drink sellers, sandwich sellers and children gawking and yelling ‘khawaja, khawaja’ whenever a white face appears. Occasionally handicrafts, colourful woven-grass items or leather sandals are available, sold by old women standing next to the tracks.

Arriving in Port Sudan, we walked until we found the Olympia Park Hotel which had been recommended to us by travellers passing through Kadugli who had mentioned that the Greek-Sudanese proprietor, Panos, occasionally served tasty Greek food. We never had a Greek meal with Panos but the Sudanese-style, Red-Sea fish he served was splendid. Panos turned out to be a large, affable man whose family had immigrated to the Sudan three generations ago. We had tea served with marvellous Greek cakes, which his wife had prepared, and talked about the history of the hotel. During the Ottoman rule, the building had been the residence of a wealthy Turk. It was bought by Panos’s grandfather who had converted it into a hotel, keeping a section of it as the family’s residence. It is a beautiful building, with ornate wooden fretwork on the balconies, carved doors, and mosaic tile floors. Panos is a member of some obscure higher order of Freemasons and under this influence sees mystical symbols in the woodwork and the mosaic patterns of the floors. He took us down the coast to Suakin which originated long ago as an Arabic spice port, and conducted us around the crumbling ruins of mortar and brick which were once the fine buildings of wealthy Ottoman rulers and, later, of the British aristocracy. The port has now silted up and is used only by small fishing boats and ‘dhows’ which come across from Yemen and Saudi Arabia.

One night, while on our way out of the hotel, we encountered on the stairway, what at first sight appeared to be the ghost of Baden-Powell wandering through the hotel. It was Panos dressed in khaki shorts and shirt, and a peculiarly shaped hat. As I stumbled on the stairs, he hitched his khaki shorts further up his waist, tightened his toggle, and provided us with a brief history of the Scout Movement in the Sudan and his role in it as a Scout Leader, before reeling off into the hot night.

We passed through Khartoum on our return trip to Kadugli. The only significant change since our last visit was the bird whistles ingeniously fitted to the brakes of taxis. Every time a driver puts his foot on the brake pedal a bird call is emitted. The whole town twitters like a congested budgy cage.

Back in Kadugli I contemplate the coming term and discuss with students their final exams. Out of thirty-two thousand students writing finals, only about five thousand will find places in the three universities, the University of Khartoum, Cairo University Extension and the Islamic University. The system is extremely competitive and the students are strained with anxiety.

Looking across at the rocky hills scarred by fire and sun, the plain swept by dry winds, I cannot believe that life will return to this desiccated landscape.

As the light fades a silence grows, spreading with the pall of white wood smoke that detaches itself from the shadowy sides of the hills and meanders through the settlements. For a brief moment this swell of silence holds and, as the night expands, breaks to fill the dark country with murmurings, voices of tired shrill children and the muezzin’s call to prayer,