They study guide books with plans, attractive photographs and minute historical detail. Arriving at a site, however, they are confronted by incomprehensible ruins filled with thistles, dust and snakes, and perhaps a peculiar-looking archaeologist measuring the fragments of a stone block while mumbling such obscurities as, ‘This secondary cutting conclusively disproves Stevens’s theories on the pre-proto-Pinakotheke!’ This experience generally induces ennui and lassitude when visits to other archaeological sites are suggested, especially if this is a first encounter. The choice of a first site to visit out of Athens may shape the visitor’s view of archaeology, and so it should be a good one.

A trip to Delphi is one of the high points of any visit to Greece. It is easily reached from Athens by car or public transportation and is on every major tour itinerary. For those with only a short time and a limited budget, the day tours are the best bet. They include a guide who generally has a better than average idea about the monuments. A major disadvantage of such tours is that they run to schedule and one is herded from major monument to major monument with little time to explore.

The ideal trip is made in your own car on a fairly elastic schedule with time for side trips. The roads are good all the way to Delphi and pass through or near a number of places worthy of a stop. Thebes is the first major town you will encounter en route from Athens and a good place for a coffee break. (Restaurant food is, alas, not a memorable culinary experience in Thebes.) Its museum is one of the finest in the provinces lurking beneath the only remaining tower of the Frankish Castle of Thebes (which was the capital of the medieval Duchy of Athens). The courtyard is crammed with marble fragments, an array of amusingly naive sculptural tombstones, a splendid mosaic depicting some months of the year and, on the wall of the museum building itself, a number of fine Byzantine marbles including a sun dial. The museum’s Mycenaean collection is in itself well-worth a trip to Thebes. It includes a number of painted burial urns from tombs near Tanagra. These urns depict scenes of mourning and a variety of decorative motifs which have parallels in later Greek art and in the art of the East. They are in the first rank of Mycenaean painting. There is also an extensive collection of miniature Mycenean figurines, a large number of finely decorated pottery vessels, and a collection of precious objects from the Mycenaean Palace of Thebes.

A very large palace beneath much of central Thebes and the scattered excavations have produced a pair of massive, ivory throne legs, storage vessels, gold and silver ornaments, furniture inlays in agate, seal stones and bronzes. One of the most startling finds was the discovery that a prince of the second half of the second millennium B.C. was an antique collector. The excavators discovered a cache of lapis lazuli (a rare blue stone from Afghanistan) cylinder seals from the area of Mesopotamia. The stone was of great value. The seals themselves are Elamite, Sumerian, Sargonic, Old Babylonia and Kassite examples, and range in date from near contemporary with the palace to over a thousand years earlier. In addition to the Mycenaean material there are large numbers of Geometric, Black-Figure and Red-Figure Greek pots. (There is one pornographic pot. Enjoy yourself trying to find it.) There are also terracottas of varying quality and some major pieces of sculpture. The most interesting is a group of grave stones with incised figures of the deceased.

There are several minor sites to visit after leaving Thebes: Gla, Orchomenos and Chaeronia. The most mysterious is the vast Mycenaean fortress of Gla, which was probably a place of refuge for troubled times used by a diverse group of minor states in Boeotia. A warning is in order since the site is a wild one and somewhat difficult to find. The ‘palace’ seems to have had several suites separated from each other for the use of a group of rulers of equal status. Orchomenos boasts a very important Byzantine church built in the Bulgarian style (you can see re-used classical column drums in the walls); a classical theatre and a large, Mycenaean tholos tomb now used as a store for a diverse and interesting group of ancient marbles. It is usually locked but a custodian can be found nearby, or, if you can manage to look very innocent and naive, you can climb over the gate. At the site of Chaeronia, the battlefield which clinched the power of Philip II of Macedon over the rest of Greece in 338 B.C. there is a rather funny-looking lion monument to the battle and a minor museum.

Continuing on the main road to Delphi, you pass through the city of Levadhia, popular souvlaki stop, which has a minor waterfall and a Frankish castle. Levadhia was the capital of the Duchy of Athens under the Catalans after 1311. The castle’s towers provide a fine view of the plain of Boeotia. After leaving Levadhia, there is a turn-off to the monastery of Osios Lucas. The great church contains some of the most important Byzantine mosaics in Greece. Returning to the main road which climbs among the mountains of the Parnassos range, you come to the village of Arakhova famed for its wool crafts. Today the many tourist shops carry woven or knit goods from all over Greece. It is a good place to buy provisions for picnics since there are few groceries in Delphi. A short drive from Arakhova brings you to the modern village of Delphi.

Ancient Delphi was the site of an oracular sanctuary of the god Apollo, famous and influential throughout the ancient world. In its heyday, during the seventh through fourth centuries B.C., vast riches poured into it and cities and rulers throughout the Greek world vied with each other in the votive monuments they built within the sanctuary precincts. There is no exact modern analogy since oracles or ‘fortune-telling’ is frowned upon by most modern religions. Under no circumstances should you think of Delphi as purveying mere mumbo-jumbo or fake oracles on the line of a gypsy at a fair. The entire process was one of deep religious significance and the most important events took place in the ‘holy-of-holies’ within the Temple of Apollo.

The ancient pilgrim would arrive in Delphi and, like you, look for a hotel or a campsite and a place to eat. The sanctuary was, of course, in the heart of the ancient city and the ancient inhabitants made their living from visitors in the same way as do their modern counterparts. There were local guides, ‘tourist shops’, inns and the like. The major oracle took place once a month on Apollo’s birthday (except for three months when he was on holiday) and the queue began early in morning. The enquirer had to offer up special, expensive, locally-made cakes on the outside altar and then sacrifice goats or sheep within the temple. These were of great profit to the townspeople. (Apollo, just got the fat, skin, bones and odd bits, the townspeople got the remainder.) Early that same morning the priestess who acted as Apollo’s voice, the Pythia, prepared herself by washing at the Castalian Spring, and, possibly, drinking water from Kassotis, chewing bay leaves, and inhaling stimulating incense. What is certain is that the middle-aged and very devout Pythia went into a self-induced trance after all the awesome ritual which preceded her entrance to the holy-of-holies and her sitting on the tripod of Apollo and speaking his words. These words, spoken while the enquirer sat very quietly with a guide behind a nearby screen, initially made no sense at all but were immediately translated into polished hexametres (an ancient Greek poetic metre) by a Priest who stood nearby. The pilgrim then returned home bearing what was often a very cryptic oracle, which would have been interpreted by a professional. On other days of the month the Pythia would use a form of lot oracle which was much less expensive than an individual sitting. (Questions would receive a yes or no answer depending on the colour of a bean randomly chosen by the Pythia.)

The oracular pronouncements were not only about personal problems: many concerned major affairs of state such as colonization, constitutional change, governmental successions, foreign affairs and religious questions. The dictates of these oracles were usually scrupulously obeyed. They were particularly significant to colonization since mariners would visit the sanctuary, dedicate monuments which they would have promised in return for a successful trip, and discuss the new things which they had seen. This information helped to determine the final wording of the hexametre oracle. If a colonizer asked which of two sites might be the best, for example, the priests would be in a good position to give a sound answer since they could draw on prior information. Most of the preserved oracles seem to be successful ones: the priests and guides in Delphi were the ones who preserved them and they had a vested interest in guarding the oracle’s reputation for infallibility.

States and individuals donated great numbers of votives to the sanctuary: trophies, statues of their successful generals, of mythical founders or ancestors, of their kings, and of powerful beasts — or of Apollo himself. Particularly precious objects were kept in buildings which we call treasuries; many cities had their own and those which did not arranged to have their citizen’s votive offerings stored in the treasuries of friendly cities. Rome’s earliest gift to Delphi was placed in the treasury of Marseilles. These buildings and the bases for the many statues are what you will see in the sanctuary today.

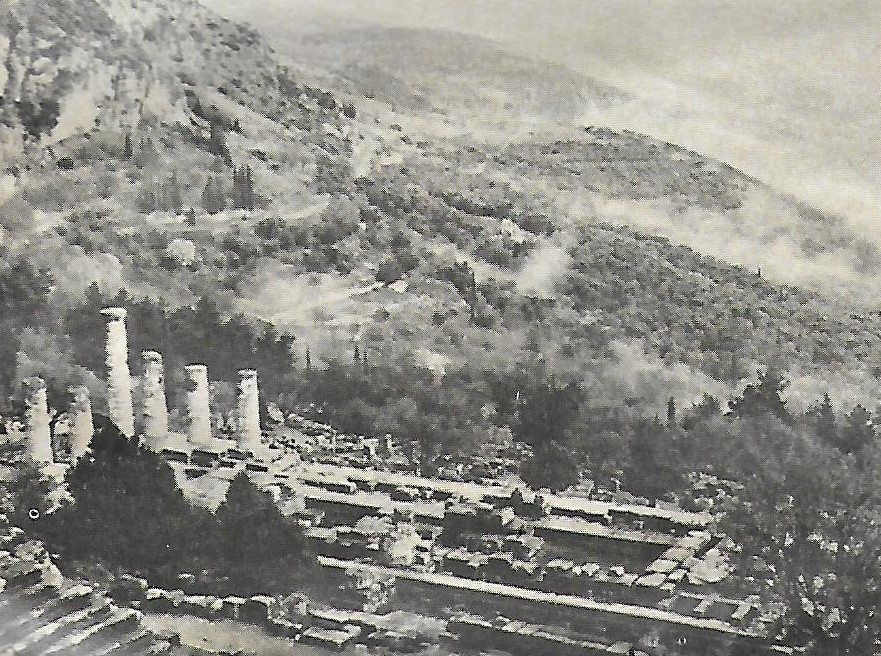

The site itself has the advantage of being the most beautifully situated in Greece. It sits on a shoulder of the Parnassos range with towering cliffs above and the Crisaean plain stretching to the sea below. The immense forest which covers the plain is composed of olive trees and is of great beauty when seen from far above in Delphi. There are five main things to see in Delphi: the Athena Sanctuary, the Gymnasium, the Apollo Sanctuary, the Stadium and the Museum. As you head from the modern town to the ancient sites, you first come to the museum. This should be visited last since the many pieces of architecture and sculpture which it houses will make more sense once you have seen the monuments from which they were removed.

A short way beyond the museum is the Apollo Sanctuary. After paying your entrance fee, you mount a flight of stairs and arrive at a paved square. This was a Roman Agora, a market place for votives and a marshaling point for processions to the Temple.

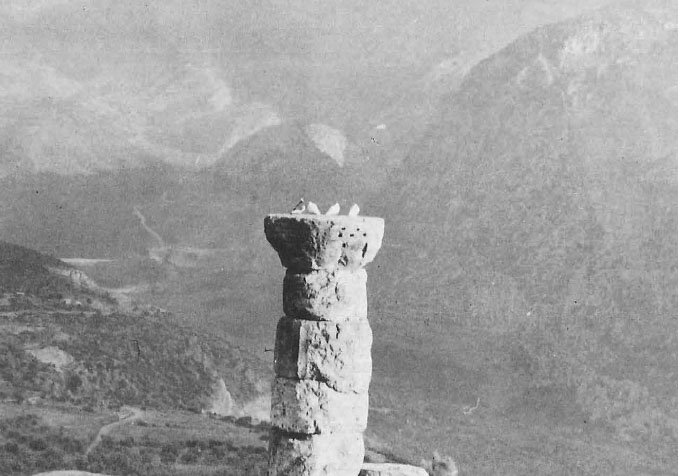

Almost all the walls you see outside the temenos or precinct wall of the sanctuary are Roman in date and belong to houses and bath buildings of the ancient town. Most of the decorative brickwork of these Roman buildings would not have been visible but would have been covered either by stucco or a marble veneer. The paved road you walk on as you go into the sanctuary temenos is called the Sacred Way and winds into the Great Temple. The road is lined with monuments and treasuries, many of which are readily identifiable either because they bear inscriptions which act as captions, or because they are described in the guide book written by the traveller Pausanius in the second century A.D. Carefully look at the building details: the way the building blocks are treated and the shape of the clamps (or their surviving cuttings) which bound them together. These technical details change over time and are of greatest importance for reliable dating of the building. Since the buildings in Delphi span the entire history of Classical Greek stoneworking, if you remember the details from well-dated and identified Delphic monuments, it will help you with the other ruins you see throughout Greece. Even poorly preserved buildings have things to say: the odd curved and hollowed out blocks in the foundation of the fifth century B.C. Sicyonian Treasury came from the earliest round building (Tholos) in Greece: it was erected by the Sicyonians in the sixth century and when it had to be torn down, only they had the right to reuse the expensive building blocks. The ably restored treasury of the Athenians tetls us another thing: you were meant to look in on the gifts but not to enter since there were no steps in ancient times. Other buildings had their functions drastically changed; the Stoa (colonnade) built by Attalos I, a king of Pergamum in Asia Minor, on a terrace above and to the right of the Apollo Temple, was bricked up and enclosed to form a reservoir for the many Roman bath buildings.

The Apollo Temple, despite the ravages of man and time, remains most impressive. You will note that many of the clamps show signs of having been dug out. The poverty-stricken inhabitants of post-Classical Greece used their ancient buildings as convenient quarries and as mines for metal (the clamps were made of iron and covered with a protective layer of lead).

Above the temple is the very well-preserved theatre and above the theatre (after a ten minute walk) is the stadium. One of the most attractive stadiums in Greece, it was constructed using the Delphic foot which was rather short (weights and measurements were not standardized in ancient times). One other major stadium using the same foot is now being excavated by archaeologists from California at the site of Nemea, near Corinth and Argos. The starting lines in Delphi are also preserved and show a different form of start than that used now. (The runners stood rather than crouched to start and their feet would be very close together).

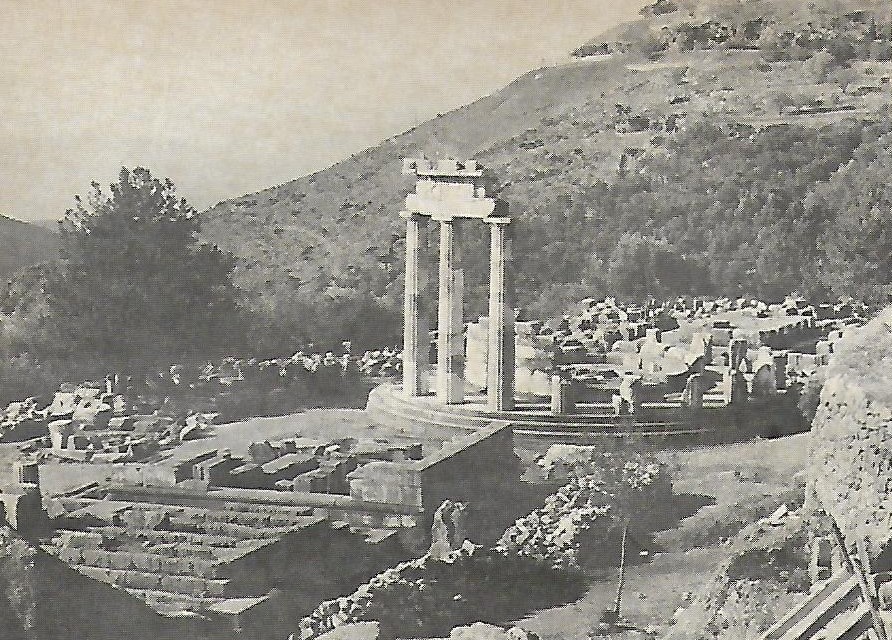

When you return to the main road below the Apollo Sanctuary, you can easily make your way to the remaining sites. Walking along, you pass the cleft in the mountain which contains the famed Castalian Spring (the water is still very good) and across the road, alongside a snack bar, you will find the path to the Gymnasium and the Athena Sanctuary. The gymnasium is not really a highpoint of the trip: it is badly overgrown and was ravaged by a monastery which stood on its site. It does, however, contain a Classical Greek swimming pool and Lord Byron’s name chiseled into a column as a memento of his visit. (He also cut his name into a block at Sounion: early travelers liked to leave records of their passing.) The rather intimate Athena Sanctuary follows after another short walk. It is most famous for the presence of the Tholos, a round building of uncertain function whose restored columns are so well-known as to be almost an emblem of Greece. (Its architect thought it important too: he wrote a book on it, now, alas, lost.) The sanctuary also contains two visible temples of Athena and the remains of a third, in the form of very flat Doric column capitals.

After a day spent among the ruins, it is best to put off the museum until the next day when you have rested. The hotels in Delphi are generally quite good and there is a camping ground on the far side of the town. The food is not exceptional. It is wise to restrict your eating to freshly grilled meat or fish, and salads.

You may prefer to stay at one of the nearby towns. Amphissa, about twenty minutes by car to the west, is an attractive market town famed for its olives. It also has a well-preserved ancient and Medieval castle on its acropolis (the large blocks are Classical or Hellenistic, the small ones are the result of repairs carried out in Medieval times). There is even a modern pill-box on its crown, a reminder of grim events of the recent past though it now seems to be used by local couples who go there to enjoy the view. There are a few nice restaurants and it might be a nice place to stay. If you speak Greek, there is also a pharmacist, Mr. Drosos Kravartoyiannos, who is a very knowledgeable local antiquaire. If you get sun-stroke looking at ruins, he can cure you while telling you everything you could possibly want to know about what you have seen! You can also stay at the port city of Itea. A somewhat better idea is a visit to the small town of Galaxidi. This was one of the great maritime towns of early modern Greece and has an architecture similar to that of the wealthier islands. It is a very restful and attractive place to visit. It is also a good place to swim.

After a break, the Museum of Delphi beckons. Outside the door is a lively mosaic from an early Christian basilica. It contains pictures of birds, fish and animals (copied from a mosaicisms pattern book since many of them are clearly not native) and has the seasons represented in the centre. Throughout your stay in the museum, tour-groups will hurtle by at amazing speed; they all look at the same things so if you pick something obscure to look at the museum may seem to be empty. The museum is really very carefully arranged. The only problem is that almost everything is worth seeing. The sculpture from Delphi can teach you a great deal about the development of Greek art. As you walk past all the sculpture you may find it interesting to compare the treatment of clothed bodies from Archaic through Classical times. At first the drapery is formal and no real sense of the body appears: only gradually do you become aware of a body beneath the clothing. By the fourth century B.C. (the Tholos sculpture especially) sculptors were virtuoso enough to produce clinging and virtually transparent drapery. You will also see many examples to prove that Ancient Greeks were also capable of bad taste. The Acanthus Column would have been rather bizarre and that little girl in the small bronzes room is just too sickeningly sweet. The small bronzes room comes after the room of the Bronze Charioteer (perhaps the most famous statue in Greece) and contains examples of many of the minor votives one would have seen in ancient days. It is dominated, however, by the marble statue of the handsome boy Antinous. Young female guides like to raise laughter by saying they think of him as their boyfriend. Alas, he had a boyfriend himself.