Photographs by Eugene Vanderpool

A LARGE open square, surrounded on all four sides by public buildings, the Agora was in all respects the centre of town. The excavation of buildings, monuments and small objects has illustrated the important role it played in all aspects of civic life. The senate chamber (bouleuterion), public office buildings (Royal Stoa, South Stoa I) and archives (metroon) have all been excavated. The law courts are represented by the discovery of bronze ballots and a water clock used to time speeches. The use of the area as a market place is suggested by the numerous shops and workrooms where potters, cobblers, bronze-workers, and sculptors made and sold their wares. Long stoas, or colonnades, provided shaded walkways for those wishing to meet friends to discuss business, politics, or philosophy, and statues and commemorative monuments reminded citizens of former triumphs. A library and concert hall met cultural needs, and numerous shrines and temples received regular worship in the area. Thus administrative, political, judicial, commercial, social, cultural and religious activities all found a place here together in the heart of ancient Athens.

The excavation of this rich area has been entrusted by the Greek state to the scholars of the American School of Classical Studies. Except for a break during World War II, work has gone forward every year since 1931. Dozens of buildings and thousands of objects dating from 3000 B. C. to the present have come to light. The excavations are administered by the American School, supported by over a hundred colleges and universities in the United States. Financing for the Agora comes largely from foundations, supplemented by private donations.

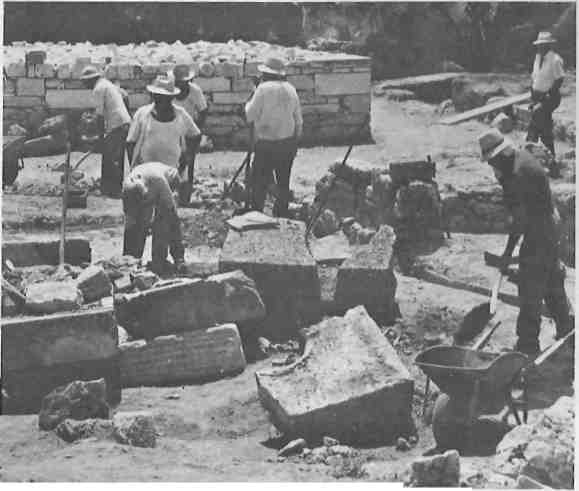

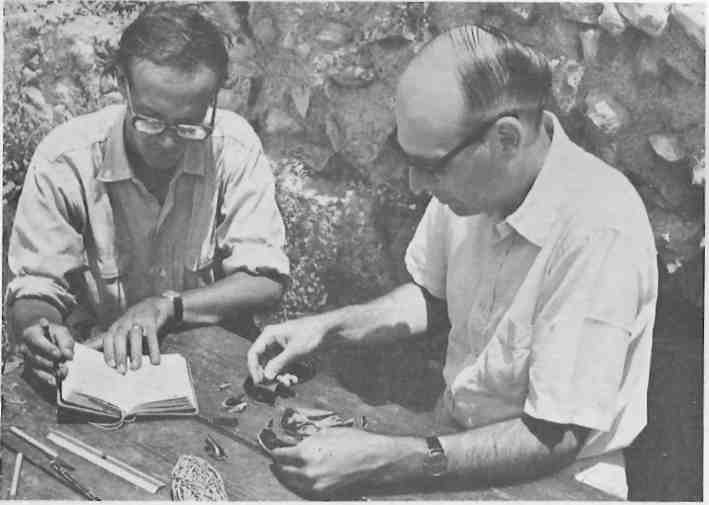

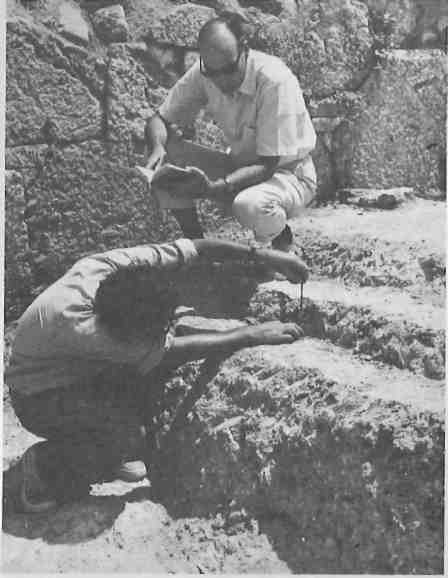

Excavations are generally carried out every year. Depending on funds and the size of the area to be explored, the season may last five weeks or five months, and the work force may vary from seven to seventy men. The work is executed by local labour, with each section under the supervision of an American archaeologist responsible for keeping the notebooks which record the daily progress of excavation. The pickmen are trained on the site and generally have ten years’ or more experience. Such training is necessary in order for them to ‘feel’ the changes in colour and texture in the earth which indicate a new layer and thus a change in period. Less skilled workmen remove the earth with shovels and wheelbarrows. The principal excavating tool is a large pickaxe, and often a handaxe or trowel is used. Most of the layers excavated contain material broken in antiquity. The dental tools and paint brushes which loom so large in the minds of laymen are generally used only for cleaning closed deposits, such as graves, where there is reason to believe objects may have survived intact.

Excavations this summer have been concentrated on a large public building which lies to the southwest of the Agora square. The building was partially cleared in the 1940s and was recently identified as the State Prison of Athens. An account of the identification, based largely on Plato’s description of the last days of Socrates, was first published in The Athenian in April 1976, by E. Vanderpool. Further exploration of the building is being carried out, to be followed by some restoration and landscaping, to make the site both comprehensible and appealing to visitors.

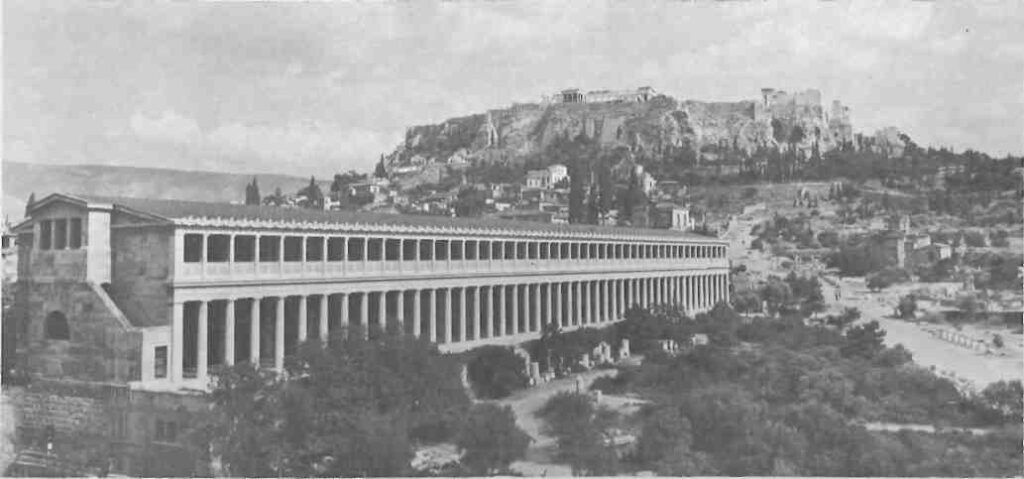

The excavator and his crew form the most visible part of the excavations, but much goes on behind the scenes, where a large staff and numerous scholars work to conserve, record, store and study the material recovered. At the Agora this important aspect of the work is housed in the Stoa of Attalos. A long colonnaded building, the stoa was first erected in the middle of the second century B.C. by King Attalos of Pergamon, who studied in Athens under the philosopher Karneades. The Stoa was reconstructed in the 1950s under Homer Thompson, the former director, to serve as the museum of the Agora excavations.

The decision to reconstruct the stoa was made when no suitable location for a museum could be located nearby. A promising spot west of the Areopagos was found to have been thickly inhabited in antiquity and the ancient remains of houses, workshops, and what now seems to be the prison, were too valuable to sacrifice. The only solution was to rebuild an ancient building and the Stoa of Attalos was the logical choice. Incorporated into the late Roman fortifications of the city, the building stood up to the roof in places, eliminating the generally difficult task of restoring the height correctly. Numerous architectural fragments permitted the exact restoration of all the elements of the superstructure, and the building as it stands today is a faithful copy of the original stoa. Several fragments of the original architecture are on display or actually incorporated into the stoa at the south end so that the visitor may judge the accuracy for himself.

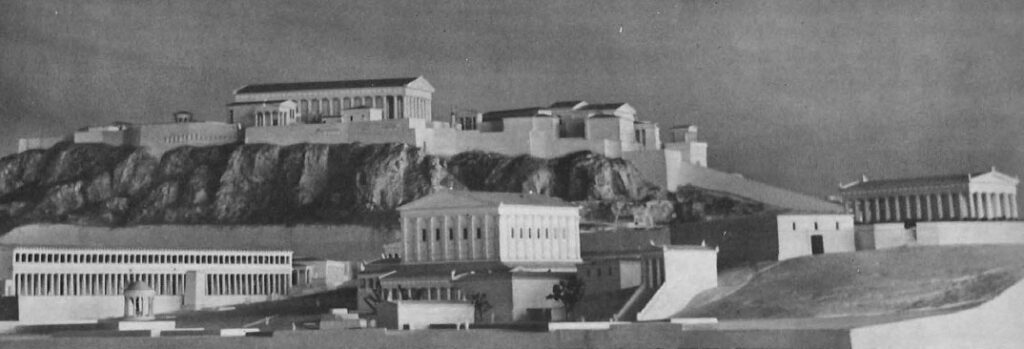

Everything found on the site is housed in the building. The ground floor has a series of public displays inside, representing the most interesting small objects discovered. There may be seen a selection of coins, pottery, jewelry, lamps, weights, measures, terra-cotta figurines, and the like. Sculpture is displayed outside in the lower colonnade. In the upper colonnade which is open during the summer months, there are models of the Agora, Acropolis, and Pnyx, and a fine general view of the entire Agora.

The stoa contains much more. In the basement are large storage rooms, where the inscriptions on stone, some seven and a half thousand of them, are kept. Because they are often fragmentary and always in ancient Greek, only a few are on display upstairs as they are of little interest to the average visitor. Their importance for our understanding of ancient Athens cannot be overemphasized, however, since the inscribed laws, treaties, honours and records represent a wealth of primary historical information—the people of Athens speaking directly to us over the centuries.

Next to the inscriptions are shelf after shelf containing boxes, bags, and tins of ‘context’ pottery fragments or sherds—which are the principal dating tools. Scientific methods, such as Carbon 14, are not yet sufficiently accurate. Coins, though readily datable, are not found often enough. Every layer, however, contains scraps of pottery and these are used for dating. Changes in technology, tastes, and foreign contacts affected pottery styles and it is possible to date those changes. Moulded bowls with relief decoration, for instance, do not appear in Athens until the late third century B.C., the result of influence from Ptolemaic Egypt.

In one sense, excavation is little more than the art of destroying evidence: once a layer has been excavated it is lost forever. The context pottery is preserved so that future scholars working on a given building site excavated years earlier will have at hand the material on which the original historical reconstruction of the building was based. All the containers of pottery are kept, representing the thousands of layers stripped away in the forty-five years of excavating at the Agora. Each is numbered and labelled and each can be tracked down in the excavation notebooks. A collection of some eight hundred amphoras, which were used for the storage and transport of wine and oil, are also kept in the basement as well as collections of sculptural and architectural fragments. Pottery, small finds, and coins are kept upstairs.

On the second storey are the museum work rooms and offices, where all the staff except excavators may be found. The size of the permanent staff varies, but some eight to ten people are at work in the building on most days. In summer, when the academic schedule frees those scholars holding university appointments abroad, the numbers swell to as many as twenty people. Among these is the director of the excavations, T.L. Shear Jr., who teaches at Princeton in the winter. When in Athens, he is at work on a book on the Royal Stoa, a small building found several years ago, which housed the law code of the city and served as the office of the king archon — the chief religious magistrate. Other scholars come for periods of a week to three months to study finds from the excavations.

The centre of the indoor operation is the records room. As the name implies, this houses all the records of the excavation. There are several hundred field notebooks which record the progress of the excavation of each area, from the demolition of the modern houses down to the stripping away of the last layer over bedrock, a task which can take several years and require the removal of as much as twenty feet of stratified deposits. Also kept here are catalogue cards for all of the inventoried objects and an extensive photographic archive. On a large bookshelf may be seen the full array of Agora publica-tions. These are geared to all levels of interest, starting with a two-page, fold-out pamphlet progressing to a series of thirty-two-page picture books, a guide to the site arid museum, and a series of twenty large archaeological volumes on various classes of antiquities from the Agora. The secretary of the excavations, Lucy Krystallis, is responsible for the upkeep of the records system. She also assists all visiting scholars. The great advantage of the stoa as a museum is that it houses both objects and complete records detailing the recovery of the objects. As such, it is one of the most valuable study collections of Greek antiquities, readily available to scholars of all nations.

As well as the records room, there is a mending room, where Spyros Spyropoulos, the Agora’s technician for twenty-five years, cleans and repairs the many objects which need his attention. Here bronze coins are cleaned in an acid bath and fragmentary pots are painstakingly pieced together and restored.

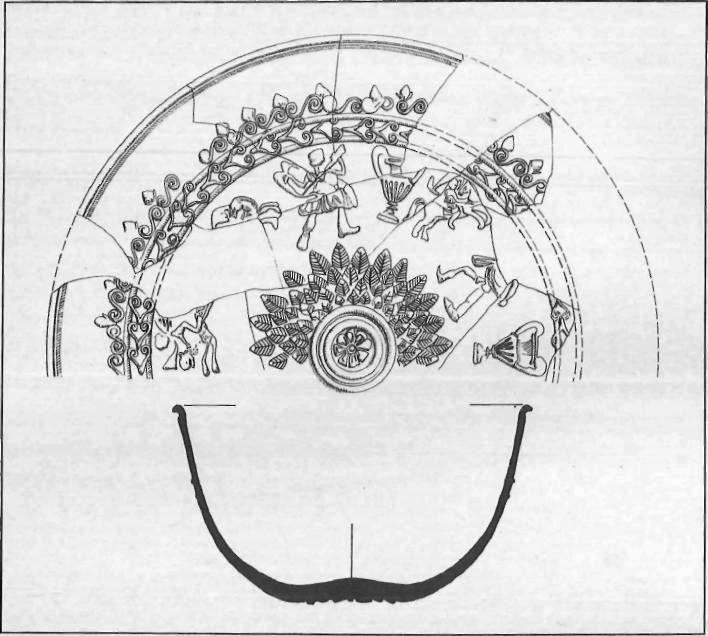

There is also a darkroom and a small library. In the latter Alan Walker, better known to readers of The Athenian as a travel, food and shopping expert, plies his real trade as numismatist. Under his careful scrutiny, corroded and seemingly illegible bronze lumps are made to yield up their dates and the names of the cities which minted them. Next door, W.B. Dinsmoor, Jr., the excavation architect, holds office. Large metal drawers hold the fruits of his labours, hundreds of perfectly executed plans, cross-sections, and restored drawings, detailing the complicated architectural history of the dozens of buildings excavated thus far. Sharing the architect’s office is artist Abigail Camp, at work on a series of detailed drawings of delicately moulded bowls, covered with relief decoration, which were made in Athens in the third and second centuries B.C.

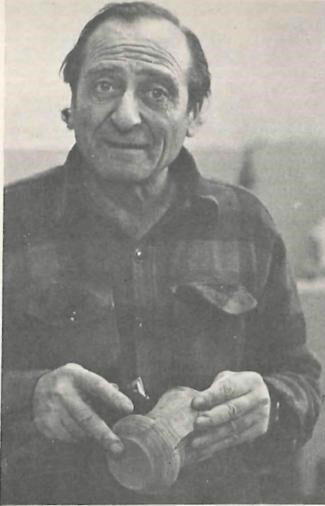

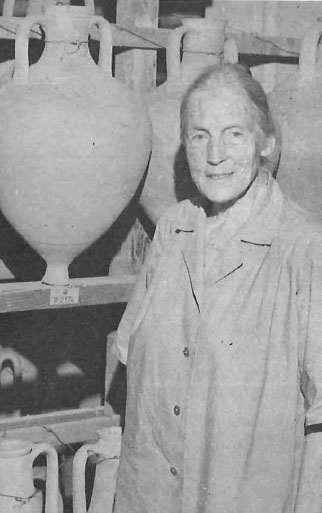

SEVERAL MEMBERS OF THE AGORA STAFF AT WORK IN THEIR OFFICES WHICH ARE HOUSED IN THE STOA OF ATTALOS.

Beyond the architect’s office is the amphora department where Virginia Grace classifies amphoras, in particular the stamps on the handles which often date the jars and identify the city of manufacture. A lifetime of study has illuminated many aspects of ancient trade in wine and oil.

These people make up the core of the larger group of archaeologists associated with the Agora. Over the years some one hundred and fifty scholars have worked for the excavations in one capacity or another, devoting themselves, for little or no pay, to the study of ancient Athens. The well-known Greek publisher, Eleni Vlachou, was once quoted in Vogue magazine as saying that this group regards the twentieth century rather in the manner of a hotel. One stays, eats, and sleeps there, but all one’s enjoyable, worthwhile existence is spent elsewhere, in more colourful and dignified times.

The future of the Agora is promising, given adequate funds and the continued good will and support of the Greek state. Two areas in particular call for further exploration. Behind the Stoa of Attalos, a broad marble-paved avenue connected the Greek and Roman Agoras in antiquity. The south side of this street was excavated in 1970-75, bringing to light a handsome marble colonnade with shops. It remains now to dig the north half of the street and thereby link the area of the Roman market with the Greek Agora into one unified archaeological park.

The north side of the Agora square is even more enticing. Here, according to literary accounts, we can hope to expose the Stoa Poikile, or Painted Stoa. Built in the first half of the fifth century B.C., the stoa was renowned in antiquity for the handsome paintings wnich decorated the walls. These were done by the leading artists of the day,and depicted among other things the great Athenian victory over the Persians at Marathon in 490 B.C. The paintings are long gone, removed as early as the fourth century after Christ, but the building draws our interest for other reasons. According to Diogenes Laertius it was in the Poikile during the 3rd century B.C. that Zeno first taught what came to be known as Stoic philosophy, a discipline which took its name from the very building — the stoa — which still lies hidden along the north side of Hadrian Street, awaiting the excavators of the Agora.