A few yards behind him a photographer, carrying a heavy camera bag over one shoulder, walked off, vainly trying to spot a taxi on the road. The driver of the limousine had looked puzzled when Zubin Mehta did not avail himself of his services. After a brief hesitation, he drove off. The photographer, still searching for a taxi, thought for a moment of hailing the limousine, but then reconsidered and decided to walk, heavy bag or not.

A little later another group emerged from the silent theatre. About a dozen people. A young man in a black velvet suit, a pretty woman wearing a strapless purple gown and others carrying sound and camera equipment, their gala clothes looking slightly rumpled after an evening of hard and concentrated work. The group included publicity people, writers, an executive television producer and two assistant producers from the United States, three cameramen and three soundmen brought in from Hamburg for the occasion. And an assorted retinue. They looked for the limousine and its driver who was supposed to take them to Piraeus for a hipboard reception honouring Zubin Mehta and the Orchestra. The driver was gone, Mehta was already off to another dinner in his honour, so they decided to go out on the town on their own.

Mehta had flown in from London the same night, arriving only minutes before the start of the concert and adding to the tense moments of the preceding two weeks. (The next morning, a televised visit to the Acropolis by the maestro was canceled).

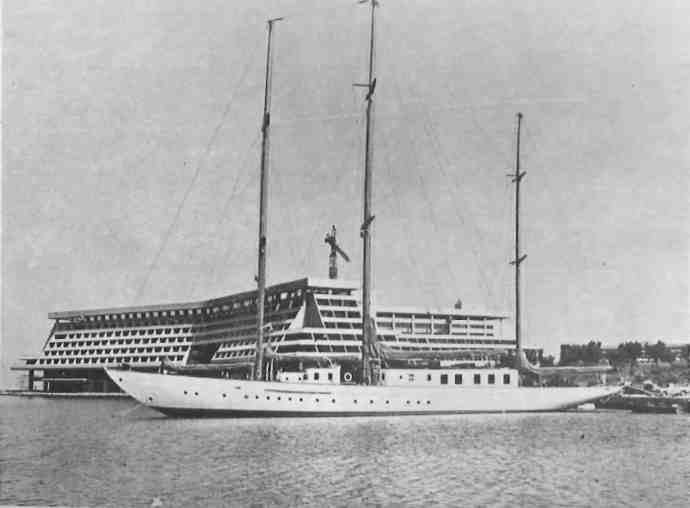

The first performance of the Los Angeles Philharmonic in Athens had ended in perfect harmony, musically as well as weatherwise, even though the limousine disappeared and Mehta did not make more than a five-minute appearance at the shipboard dinner. The rain that had been gathering in heavy clouds over Athens did not fall until after the second concert began the next night. It added a final highlight to the unusual experiences of a select group of people, some two hundred in ” who had been travelling through the Mediterranean for a fortnight surrounded by music, symphonic music that is, aboard the MTS Danae, one of the Carras Line’s two luxury cruise ships.

None of the little hitches and tense situations involved in keeping a vast supporting cast on its toes will be evident when the result of this unusual enterprise — a full philharmonic orchestra of one hundred and four men and women, traveling aboard ship and playing for two weeks for a group of passengers outnumbering them barely two to one — will be seen over public television in the United States in February 1978. The program will be one of six specials on the arts, all underwritten by a grant from Atlantic Richfield Oil. (Of the other five specials, one will be devoted to Beverly Sills and the San Diego Opera Company. The remaining four performances will take place at Wolf Trap Farm, a national park in Vienna, Virginia, operated by the U.S. Government’s Park Service exclusively for the performing arts. There will be a concert with Benny Goodman, a performance by the Martha Graham Dance Company, a bluegrass concert and an evening of black ballet and traditional jazz.)

The people who had travelled on the ‘Philharmonic Cruise’ aboard the MTS Danae were mostly Americans, with a sprinkling of Europeans. More or less middle-aged, they were described as ‘staid and conservative’. In everybody’s opinion they were people who took music very seriously. They must have. Billed as ‘very expensive’, the two-week cruise cost, per person, anywhere from $1,775 (for an inside cabin) to $5,840 (for a penthouse suite with its own private balcony), not counting the airfare to Southern France. It took them from Villefranche to Barcelona, from Palma de Majorca, to several ports in Italy, from Kusadasi to Porto Carras and, finally, to Piraeus and the concert at the Herodes Atticus Theatre.

Along the way, wherever the ship stopped, there were concerts arranged in unusual settings. One participant described the concert in Barcelona’s Palacio de la Musica as breathtakingly beautiful, not only because of the music. The surroundings and the moonlight contributed to make it a unique experience. ‘Another highlight was the concert in Palma de Majorca,’ he added. ‘We were taken to Villa Vlademosa, where George Sand and Frederic Chopin lived. Christina Walevska, one of the soloists on board, and a young cellist of the orchestra, gave a Chopin recital.

Not only was there music, but there were lectures by a musicologist on the pieces played in the concerts. There were panel discussions about the functioning of an orchestra and how it selects its program. Passengers who were amateur musicians participated and played with the members of the orchestra.

Above all, there was the proximity to the musicians. ‘They were thoroughly professional,’ said one observer. They live and love music. Even during the day, when nothing was scheduled, you could hear them practicing and playing in their cabins.’ They were not musicians somewhere up on stage removed from the listeners. ‘There was an unusual interchange between passengers and musicians,’ he continued. ‘It was a wholly different experience.’

The television coverage, the publicity, the magnitude of the supporting structure, evident to only a few on the evening of the concert, was nothing unusual. Having a renowned symphonic orchestra on board one of their ships was another scoop for the Carras Lines and added another feather to John Carras’ cap. The Danae was the first passenger ship to carry American tourists to Communist China (in January 1977). Her sister ship, the Daphne was the first one to cruise to Havana, Cuba, with the Jazz Festival, just a few weeks ago. (Further trips to Havana, the first officially sanctioned exchange of tourists from the United States, planned for the coming months have been canceled for the time being, however, because of pressures exerted by exile groups in the United States.)

The ships have every amenity on board to make a passenger ‘very comfortable’. Each has saunas and a Lancome beauty centre; some cabins have their own bar-refrigerator, and all have full-size bathtubs; and there is a complete theatre. The ships’ furnishings carry such brand names as Knoll International and Herman Miller. Dinner is served on Rosenthal China. Looking at the lovely and lavishly-produced pamphlets, one might come to the conclusion that none of the passengers is over thirty and all are ready for the cover of Vogue.

There are those who prefer chamber music to a full philharmonic orchestra. If one’s taste leans towards Bellini and Palestrina, Corelli and Cimarosa, there is the ‘Periplo Musicale, Opus ΧΙΙI in late autumn, a cruise on the Danae through the Adriatic Sea and the Western Mediterranean to the accompaniment of the Italian baroque group, I Musici. What of those who do take their vacations seriously (as the Carras group thinks they should be taken), but do not care for music? For those interested in painting, there is ‘The Canvas and the Brush’ cruise. Leading art authorities from the United States and Europe will expound on what the passengers will see in Pisa, Florence and Siena, Pompeii and Mystra. ‘Byzantium’ is the theme of yet another cruise. Venice, Ravenna, Chios, Patmos, Istanbul are along its route.

The cruise ‘Aurora’ explores the land and history of the Norsemen. There is a wine-tasting cruise, which skims the coasts of France, Portugal, Spain, and Madeira. For gourmets there is another cruise, carrying on board such illustrious personalties as Paul Bocuse, the former chef at the Elysee Palace, Gaston Le Notre, Paris’ most famous pastry chef, and Roger Verge. The advertising booklet informs us that on a previous cruise eight-hundred magnums of champagne were consumed, as well as fifteen-hundred bottles of wine, one-hundred-and-twenty kilos of pate de foie gras and sixty kilos of caviar. The chefs demonstrate their art on board for the scholarly minded.

For those who have already ‘done’ the Mediterranean and European coasts, there are other trips. The ‘Journey to the Kingdom of the Sun God’ begins in Miami and cruises all around the coast of South America, for a total of fifty-one nights and days. And finally, for those who have the time and the necessary financial backing, there is the eighty-nine day voyage on the ‘Great Spice Road to the Distant East’. It carries a price tag of $5,730 minimum and an $18,805 maximum (for a penthouse suite, per person) for the full tour, with the option of spending as little as an extra $897.50 (for the economy minded) or as much as $4,188 (for those inclined to splurge) on shore excursions. One does get a lot for one’s money, including a more-or-less full university faculty to lecture on the art, music, and history of the places to be visited.

All this and more is part of the ‘Carras Concept’ of tourism which, according to the Carras interpretation, is one of perfection and attention to the minutest detail. ‘We aim to please the American tourist, primarily,’ says one of their employees. ‘Isn’t he one of the most exacting in his demands?’

Lately a feature of many Carras cruises has been a stop at Porto Carras, a vast agricultural and tourist complex on the middle finger of Halkidiki, on a forty-five-hundred acre tract. Described by some as a ‘benefactor’ of Greece who has created new agricultural concepts in Sithonia, introduced new cattle breeds and cultivated wines imported from France, and expects never to retrieve all the money he has poured into it (sixty-five million dollars, so far, apart from money invested by the Greek government), John Carras coddles his ‘baby’, Porto Carras. Reading about it is to skip from one superlative to another. Two hotels, with over seventeen-hundred beds, an inn sleeping another one hundred and sixty-nine, and ‘built in the style of the monasteries of Mount Athos’ (air-conditioned, though), plus two hundred and fifty villas forming ultimately a large village are being built. Add to this twenty-six restaurants, night clubs and discotheques, a marina accommodating one hundred and eighty boats, banks, a post office, laundry, dry cleaner, a fully equipped hospital unit, cinema, a nursery for children, plus a convention centre providing the latest stock market prices, three telex lines and the services of a travel agency. There will be three thousand telephones and as a bonus to its customers, internal phone calls will be free of charge.

What may sound like a magnanimous gesture, providing work and income to an area formerly little developed, has been described by others as a monstrous white elephant. To judge from published accounts and pictures of the models, the ‘idea of the Macedonian village inspired by the regional architecture of Mount Athos’ does not immediately come to mind. It has been likened to Miami Beach with touches of such new creations as Columbia, a town built from scratch outside Washington, D.C. Not to speak of Levittown.

Be this as it may, there are those who will enjoy this kind of surrounding, those who value services and expect superb functioning, whether in Kuala Lumpur or in Djibouti. Floating in a luxurious ship surrounded by beautiful music performed by expert musicians for two weeks, with the likes of Zubin Mehta and his orchestra, is surely an extraordinary experience. But one man’s meat is another man’s poison and there are others whose tastes run towards something simpler than Porto Carras. Perhaps to accommodations in a real Macedonian village rather than air-conditioned opulence by the sea. The Halkidiki coast, lovely as it is, is quickly developing into another Sounion Road, where unretrievable beauty has been destroyed by a building mania unequaled elsewhere. The Florida Everglades, now protected as a national park, were just a natural part of the landscape of Florida — before the Golden Coast giants such as the Miramar and the Deauville were built.