The two main characters in the film are a flighty actress, played by Mercouri, and an American housewife, played by Ellen Burstyn, who murders her children when her husband abandons her for another woman. The actress, in the process of rehearsing for her stage role of Medea, becomes obsessed with the personality of the other woman whose intense feelings for her husband drove her to kill her offspring.

Melina, wearing a multi-coloured, loose-flowing robe, is getting ready to play a scene before the cameras. World-weary, frail and vulnerable, she is standing by a narrow staircase on the movie set at the Kaluta Theatre in Athens. Cameras, lights, microphones and the attention of the ten-man crew are focused on her. Dassin, who wrote the script for this film, is showing her exactly how he wants the scene played. He grimaces like a satyr and contorts his body into vivid imitation of a crazed woman’s agonized gestures. Mercouri watches him intently.

‘Pame! Let’s go!’ shouts Dassin. ‘Moteur! Roll the cameras!’

Suddenly a moan arises from that slight figure by the staircase, a heartrending plaint. ‘Not naked! Not naked!’ cries the actress in agony as her manageress, played by Betty Valassy, tries to lift Medea’s robe from her shoulders. The intensity of the scene is overwhelming. Mercouri appears draiped. ‘It’s a take,’ says Dassin quietly.

In the next sequence, Andreas Voutsinas, in the role of the play’s director, is shouting angrily and dramatically at the actress: ‘Fake! Fake! Fake!’ A chorus of fourteen women, dressed in black, is walking rapidly around in a circle, frenziedly repeating: ‘Strip! Strip! Strip!’ It is still all part of the nightmare.

‘Strip!’ Dassin explains, ‘is what the American director has told his actress to do—to strip herself of all that garbage, of all the fakery that is part of her personality, in order to be able to play Medea.’

He protested when I asked if there is any similarity between the actress in the film and Melina. ‘The only similarity is that both Melina and the actress are playing Medea on the stage.’

Mercouri reappears on the set wearing a skin-tight, flesh-coloured plastic cap which covers her hair and makes her look bald.

‘You look like a man,’ says Despo, the Greek character actress who is playing the prompter in the film. Dassin takes one unbelieving look and shouts, ‘My Belissima!’ and hugs his wife.

Dassin is in the habit of speaking three languages simultaneously. In one breath, he says: ‘Va a ton miroir maintenant, cherie. Put on some mascara, ke tha doume pos tha yirisoume afto to prama!’

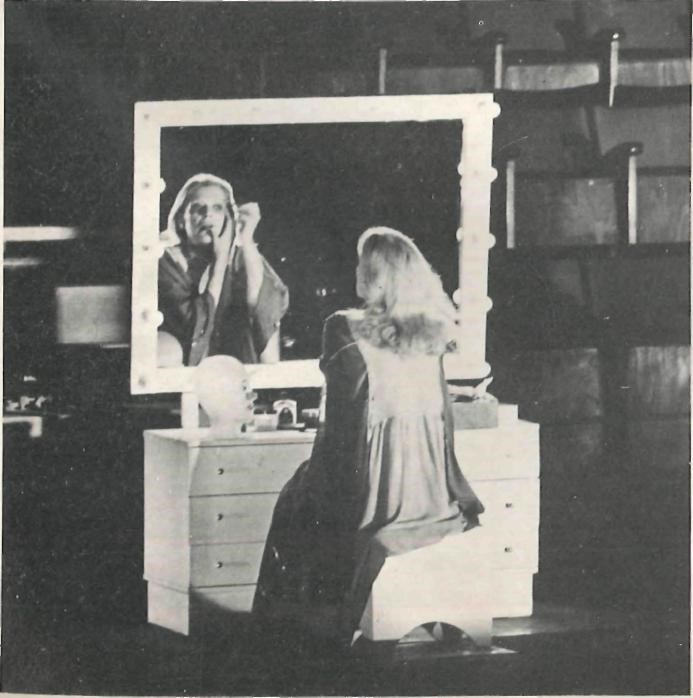

Melina is ready to play the next scene which takes place in a dressing room. She is sitting in front of a dressing-table mirror. All that is visible in the lighted mirror are huge, dark melancholy eyes and a full, wide, down turned mouth in a pale oval setting. Visconti’s makeup man who is in town to do makeup for Dassin’s film is placing a wide purple ribbon around her ‘bald’ head. Melina hates that ribbon. She absolutely does not want it on. She looks at herself in the mirror with utter disgust and contempt. The atmosphere is volcanic. Mercouri is on the verge of a monumental tantrum. Furiously she beats both her fists on the dressing room table and spits out: ‘Skata! Skata! Skata!‘ in escalating crescendos.

‘Darling, please!’ says Dassin from the back of the room, in a soft yet commanding tone.

‘Don’t pay any attention,’ says Despo, Mercouri’s longtime friend. She is wonderful! She has the heart of a small child. Let her cry a bit and it’ll all be over.’

That seems to be the general opinion. The members of the cast love Dassin and Melina. Most of them have worked in many of Dassin’s films. It’s one big family. They are familiar with and tolerant of each other’s idiosyncracies. They respect each other. Shooting a good film is the prime consideration.

The sequence with the ribbon has been shot. Mercouri is still sitting at the dressing table. ‘Can’t we try it next without the ribbon?’ she asks in a tiny, plaintive voice.

‘Leave it on for the time being, darling,’ says Dassin. Melina plays the rest of the scene with the ribbon on.

The title of the film has yet to be decided. It will probably be called either A Dream of Passion or Maya and Brenda. It is Dassin’s fourth feature film to be made in Greece, The others were He Who Must Die, and Christ Re-crucified, based on the Kazantzakis’ novels, Phaedra and Never on Sunday which was released in 1960 and was his most successful movie.

The way the idea for Never on Sunday came to me is a rather funny story,’ says Dassin. It happened exactly as Melina described it in her book, I Am Born Greek. ‘According to her account, it all began on a Sunday morning at the breakfast table when her mother asked Dassin if he would give her permission to express an opinion about a movie she had seen the night before. The insinuation was that Dassin was rather opinionated, at least when it came to films.

As Mercouri describes it, Dassin suddenly brought both hands to his lips and held them there. ‘I have an idea for a film,5 he murmured. ‘It will be the story of a man who is always trying to impose his opinions on other people. He is American, a little naive, a sort of Boy Scout. Wherever he goes, he tries to recreate the American way of life and succeeds only in rendering everybody unhappy, in the happiest of circles. He meets a woman. She is Greek. She is so happy. He can’t stand it. The story takes place in the Port of Piraeus.’

Never on Sunday turned out to be an international success. It depicted a prostitute named Ilya who loved to live and to love. It is she, finally, who exerts a tremendous influence on Homer Thrace, the naive American, played by Jules Dassin, who was attracted by her vitality, spontaneity and general ‘joie de vivre’.

I know that I am a bad actor or an actor not to be trusted,’ says Dassin. ‘The few times that I’ve acted have never been by choice. It happened in Never on Sunday that we didn’t have enough money to pay anyone else.’

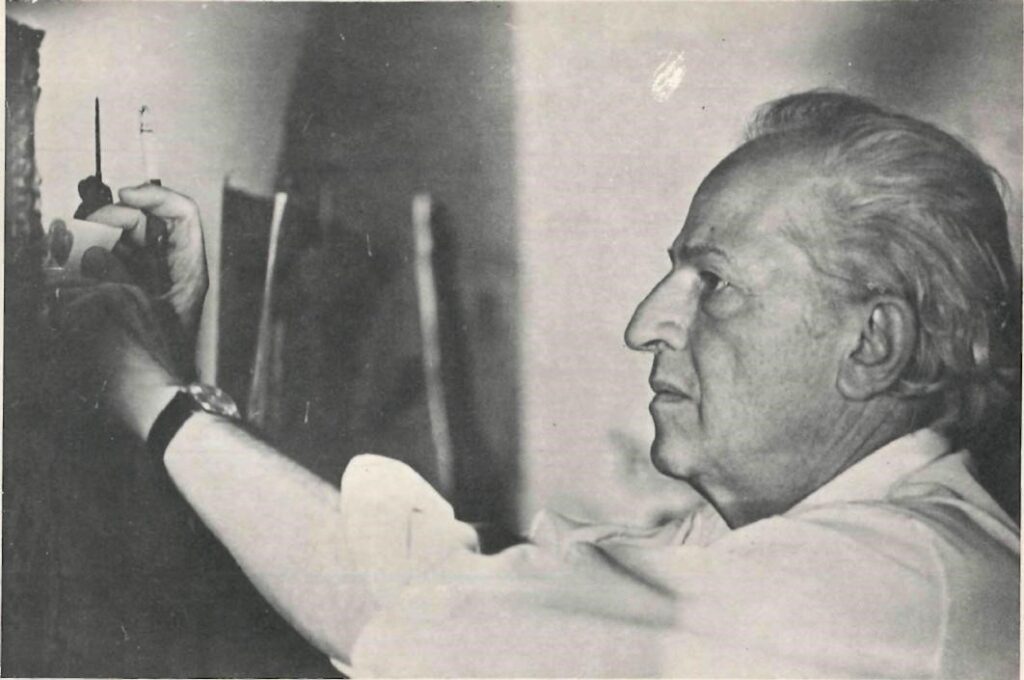

THE sixty-five-year-old Dassin is sitting in the spacious living room of his luxurious triplex apartment in Kolonaki. He is surrounded bv books, records, flowers and exquisite oriental rugs. He is of medium height, with silver-white hair and striking oblong blue eyes that sparkle. He is dressed informally but with flair. He exudes a youthful energy, self-confidence, discipline, humour—a forceful personality. There is a bit of the showman in his manner, a touch of flamboyance. He seems to enjoy the plush, yet refined setting of his home.

A different, sensitive personality emerges as he recalls his youth in New York, his struggle through the depression years, and above all, the McCarthy Witchhunts which drove him to Europe where, still under a stigma, he was able to work only sporadically for quite a few years.

Born of Russian-Jewish parents who emigrated to the United States in the early 1900s, Dassin was raised in Harlem. Τ always wanted to make a film about my mother, my family, my world in Harlem,’ he says wistfully. ‘It was a fascinating place. The four major minority groups at that time, in the 1920s, were the blacks, the Jews, the Irish and the Italians. They were all very well manipulated to be antagonistic towards each other. It was a tremendously interesting time in America’s history.’

Struggling through the depression years, Dassin started his career in show business as a radio script writer and an actor. In 1941 he joined the MGM studios in Hollywood, where, after a short stint as assistant to Alfred Hitchcock, he quickly moved on to direct features such as Nazi Agent (1942), the Canterville Ghost (1944), Brute Force (1947) and Naked City (1948), among others.

Playwright Bertold Brecht and director Max Reinhardt, refugees from Nazi Germany, were in Hollywood in those days and contributed their considerable talents to the budding film industry. They strongly influenced Dassin in his formative years as a film director.

With the emergence of the McCarthy Era in the fate 1940s, Dassin’s world suddenly collapsed, as it did for millions of liberal-minded Americans throughout the country. The hysteria which affected the universities, the scientific community, the government, and virtually every institution in America, also affected Hollywood. In 1947, The Hollywood Ten’, a group of writers, producers and directors refused, on grounds of principle, to cooperate with the U.S. House Un-American Activities Committee. Accused of being under the influence of left-wing subversives and of turning out communist propaganda films, the major studios were intimidated into compiling black lists of people in the industry whose ‘loyalty’ was allegedly in question. Among the thousands of directors, writers and actors thus branded were some of filmdom’s most gifted artists, among them Charlie Chaplin, Lillian Hellman, Dashiell Hammett — and Jules Dassin.

‘What a joke to accuse Hollywood of producing communist movies!’ says Dassin incredulously.

McCarthyism, part of the cold war atmosphere, was a moment of national sickness, from which, I think, for the most part, we have recovered. It had nothing really to do with anyone’s individual beliefs, but was a means of creating an atmosphere of fear and intimidation, in order to control.’

After three years of unemployment, Dassin left the United States for France, where, in 1953, he was engaged by a French producer to direct a film with comedian Fernandel. Two days before the filming began, the producer learned that a film directed by Jules Dassin would never be distributed in the United States. Dassin was thanked for his services and summarily dismissed. French cinema circles were in an uproar and voiced strong protest, but to no avail. Dassin was made an honorary member of the French Filmmakers’ Guild.

It was not until 19S4 that Dassin was given the opportunity to write the script and direct Rififi, based on a novel by Auguste Breton. Produced on a shoestring budget, the prize-winning film was France’s entry at the Cannes film festival. Rififi, as well as his next film, He Who Must Die, were shown in the United Stales only by small film distributors. The major distributors insisted that Dassin sign a declaration stating that he had been led astray by ‘subversive organizations’ and that he repented the errors of his youth. If he refused to sign, his name would not appear in the film credits. Dassin refused.

Of that difficult period in his life, Dassin says: ‘It was much beyond struggling to make movies. I was really struggling to stay alive. When you deprive a man of work, you hit him in a very central spot,’ he emphasized, pointing to his abdomen. Τ was one of the lucky ones. I was only kept out of work for five years. Others were out of a job for fifteen years. Many were destroyed.’

During those difficult years Dassin never thought of changing his profession and never doubted his ability. ‘Everyone understood that one’s talents were not the issue. I don’t think anyone said “I am a bad doctor”, or “I am a bad writer” or “a bad university professor”.’

It was in Cannes during the showing of Rififi that Dassin met Melina Mercouri, who was starring in Michael Cacoyannis’s, Stella, another entry in the Festival. It was love at first sight for both. According to Mercouri’s account, they went for exhausting all-day walks around Cannes—even though she did not enjoy walking all that much—but she was fascinated by the man with the striking blue eyes. When it came time to part, Dassin told her, ‘I’m hooked,* an expression she did not then understand. They have been together now for twenty-one years. The endurance of the relationship Dassin attributes to the fact that they ‘basically like each other’. And what is Mercouri really like? ‘Unpredictable!’ he says laughingly.

Since then, Mercouri has played in almost all of Dassin’s movies. She had leading parts in He Who Must Die, Never on Sunday, Phaedra, Topkapi, Promise at Dawn and now ‘Medea‘. She would not have it any other way. Ί was always horribly jealous at the idea of Julie making a film without mc,’ she writes in her book. Ί don’t like to have him work with an actress other than myself. The relations between the director and the leading lady are by nature too intimate. But I must confess that I would even be jealous if he made a film with an all-male cast.’

After an absence of some fifteen years, Dassin returned to the United States in 1967 where he made the film Uptight which dealt with being black in America. The film, shot in Cleveland, had an all-black cast. ‘Julie finally found a good excuse not to use me in one of his films,’ writes Melina ruefully. Uptight was one of the many social-protest films Jules Dassin tried to make throughout his career. ‘As far as his profession as film director is concerned,’ explains Melina, ‘Julie is slightly schizophrenic. He believes that films are only worthwhile if they educate, inspire, protest. At the same time, he loves to hear his audience laugh. Although he is quite happy while making a purely entertaining picture, he is invariably always a little ashamed of it afterwards.’

Running like a thread through Dassin’s life are the obstacles he encountered when attempting to make films with a social message. Unsure of the commercial value of such ‘protest’ pictures, producers usually balked at the last moment and refused to invest in them. Uptight had very limited distribution. Ί think that I made it too early,’ says Dassin. ‘Films on the black theme only became popular six or seven years later. In 1967 many theatre owners, afraid of violence, refused to show it.’

With much emotion and regret, he says: ‘One film that I felt very deeply about dealt critically with the American war action in Vietnam. It was a fictional story based on research I did in Vietnam in 1971. It would have been a wonderful film! We had finished the script, were close to shooting and had begun casting. Suddenly, the producer who had already spent quite a bit of money on the project backed out. He was an American industrialist, a conservative who wanted to be a liberal and who realized what it [liberalism] would cost him.’

As a politically conscious person, he fully supported Mercouri’s public criticism of the 1967-74 dictatorship which had deprived her of her citizenship and would not allow her to visit her homeland. They spent the junta years in New York. In 1974 Dassin made a documentary about the November 1973 massacre at the Polytechnic in Athens. It was called The Rehearsalbut was not shown on any broad scale.

‘Are you happy with the way the political situation has developed in Greece since the fall of the junta?’

‘No, I am not. However, it is certainly an improvement over the years of the colonels. The fact is that there are too many divisions here among the people and among political groups. But I am not too pessimistic about the future.’

‘Is it this fascist element to be found here that makes you unhappy?’

‘Bravo!’

‘Do you think that the Greek population as a whole showed enough active resistance during the years of the junta?’

‘I think that that matter is seriously misunderstood. It is very, very difficult to operate and protest under a police state; but the Greeks had their own way of resisting. They kept this gang here so isolated. The regime never really got active support on any broad level. And yet when they had the occasion, the general population did show their active resistance — at the Papandreou funeral, at the Seferis funeral — and we should never forget the Polytechnic’

‘Americans seem to be fascinated with this Zorba-like quality, this joy of living expressed by Greeks.”

‘I don’t think that Zorba really represents the Greek people. I do think that the Greeks have a better sense than most people that life should offer amusement, that life should offer pleasures — but I don’t know how many of the Greek people actually achieve it. There are unfortunately too few Zorbas. That is not my image of Greeks or of Greece.’

‘What is your image of Greece?’

‘Basically, I think, based on a political judgment, Greece is a country that has never really tasted its potential. It has never really achieved the progress, the freedom, the democracy that they themselves invented.’

‘One senses, however, that you love this country. What is it about Greece that attracts you so?’

‘It has to do with my family life, with my wife being Greek, with attachments that have grown now for some twenty-one years; with the poets, the past, the people, the culture.’

Dassin has three children from an earlier marriage. His son, Joe, a popular singer in France, has been appearing this summer at an Athenian nightspot and is frequently seen on local television.

‘They all make music. My eldest daughter composes music. My other daughter writes poetry and has written the words to many of Joe’s songs. They live in Paris.’

‘Are you planning to stay in Greece?’

Of course, I’ll do some travelling, but yes, I am staying here. It is my home.’