Confronted by these myriad exams, some members of the faculty began to ponder the need for a single universally recognized secondary school diploma that would serve as a standardized yardstick among universities and provide students with an international passport to education. The result was the international Baccalaureate now affiliated with UNESCO and recognized by forty-four countries throughout the world.

A FEW months ago the American Community School of Athens received an inquiry from a young girl in India whose father was, being transferred to Athens. She would be here for only one year, after which her family would move to Copenhagen.

At the end of her second year in Europe, she would return to India to enter university. To adjust to two new systems in each of her final two years of secondary schooling would clearly be difficult. The International Baccalaureate (the IB) program, however, would allow hex to minimize such a disruption and to emerge with a diploma readily accepted by universities in India.

As the world’s population has become increasingly mobile, education has become a more complex problem. Adjusting from one educational system to another, often in a foreign language, is difficult at any age. For students completing their secondary education, it is particularly crucial, especially if the student intends to go on to university. The concept of a standarized program of study seems so obvious in this era that it is surprising that the IB came into existence little more than ten years ago. Since that time, however, demand has spread rapidly, virtually throughout Europe and to other continents. This is accounted for not only because of its international recognition but because of the unusual opportunities the two-year program offers to those who are academically inclined and enjoy a challenging regimen of study.

Although European in design and concept, the program is useful to all students. From 1970 to 1975 the students in the program were of nationalities from around the world. (Thirty-four were from China). They were enrolled in schools in twenty-three countries, and upon graduation entered universities in thirty-nine countries. (The current figures are still higher.) Graduates of the IB program have entered the most prestigious universities in Western Europe, including Oxford and Cambridge, some Eastern European countries, the Middle and Far East, and North and South America. These students have received advanced standing at most American universities. (Harvard gives a full year credit to IB diploma holders.)

Begun in 1964, the first years of the IB project were devoted to developing the curriculum. About one hundred seminars attended by educators from many countries were held for this purpose. In 1968 the. International Baccalaureate Office (IBO) was set up as a foundation under Swiss law as an international, non-governmental organization affiliated with UNESCO. It is financed by private foundations and administered by an international council composed of major educators from several nations. At UNESCO’s 1974 General Conference, a resolution was passed with the support of nearly seventy nations calling for closer collaboration with IBO with a view to its establishment under permanent UN control.

The IB program is divided into six subject areas. Each school chooses the specific subjects it will offer in each of these areas as well as the working language and foreign languages to be taught. The curricula within each subject area are clearly defined and teachers must follow IB’s prescribed program although some individual discretion is allowed. The subject areas are:

- Language A, the student’s working language. This includes the study of world literature in translation.

- Language B, a foreign language. Bilingual students, however, may elect a second Language A and follow that curriculum. A student may also write some of his exams in other subjects in his second language to qualify for the special distinction of a Bilingual Diploma.

- The Study of Man. One of the following: history, geography, economics, philosophy, psychology, or social anthropology.

- Experimental sciences. One of the following: biology, physics, chemistry, physical science, scientific studies.

- Mathematics.

- One of the following: Art (art and design or music), a third language (classical or modern), a second subject from the Study of Man, a second subject from the experimental sciences, further mathematics, or a syllabus submitted by the individual school and approved by IBO.

For the present, English will be the officially used language at ACS. As a second language —or Language Β— ACS will offer French, but plans to offer Greek in the near future.

In addition to these courses students must engage satisfactorily in creative or social activities and participate in a course in the Theory of Knowledge. The latter takes the form of an interdisciplinary seminar. It is intended to lead the student to discover the relationship between the various subjects and their relevance to one’s environment, and to provide students with a more profound understanding of the material they have assimilated.

ACS will offer a set of IB subjects which will qualify students to sit for diploma examinations. At the end of the second year of intensive work, the student sits for three higher level examinations. The chief examiners are primarily members of the faculties at recognized European (there are several from Oxford) and American universities.

Although the IB program is without a doubt challenging —it is recommended that students have at least a B average before embarking on it— within its framework there is considerable flexibility. The emphasis is on disciplinary and interdisciplinary skills but the wide number of subjects within most of the areas allow considerable choice so that students may select courses of particular interest to them with a view to further academic endeavours, or their professional careers.

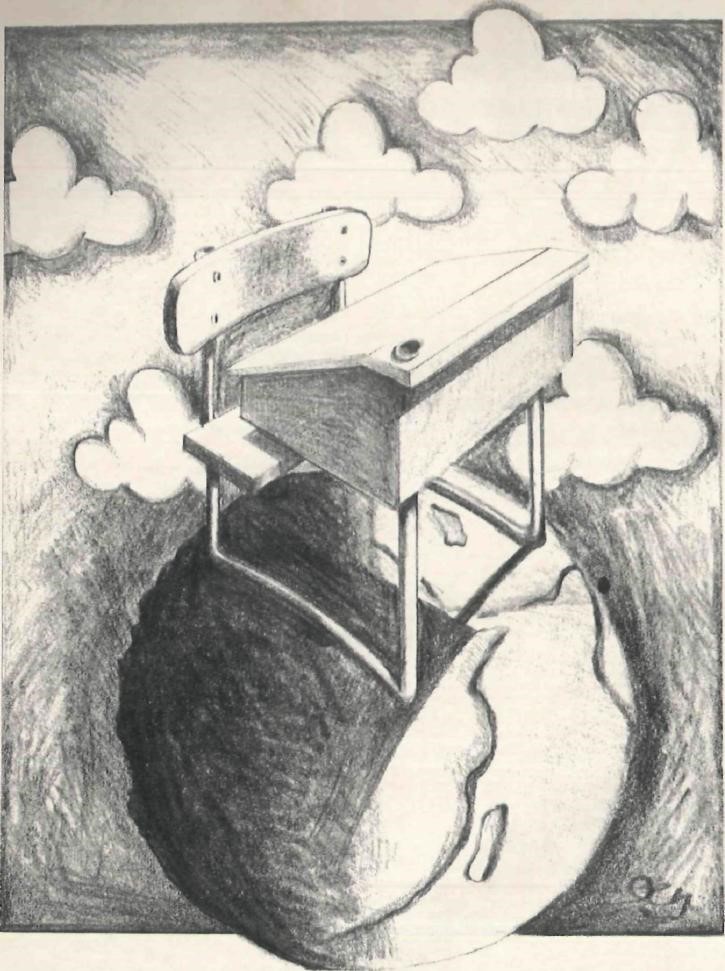

The IB is clearly the omen of the future. Perhaps one of the most rewarding aspects is that it releases students from the educational strait-jackets which they must don upon entering the secondary school educational system of any given country. Yet the British, French, German, Australian or American student who completes the IB program can return to his own national university system or apply to a university anywhere in the world without spending an extra year or several years fulfilling particular requirements.

The IB, then, can be viewed as an international passport to education enabling students from varied backgrounds to undertake a uniform and established international diploma program. The technological advancements of the twentieth century will demand, increasingly, an educational system which can realistically adapt to our shrinking world.