Photographs by Eugene Vanderpooi

‘We make the profession, it’s not the profession that makes us. It may influence us, of course. Sometimes, I get so upset that I have to pull over to calm down. Sometimes when I get home, I cry… I like people. I wonder why some, when they enter my taxi are so inhuman.’

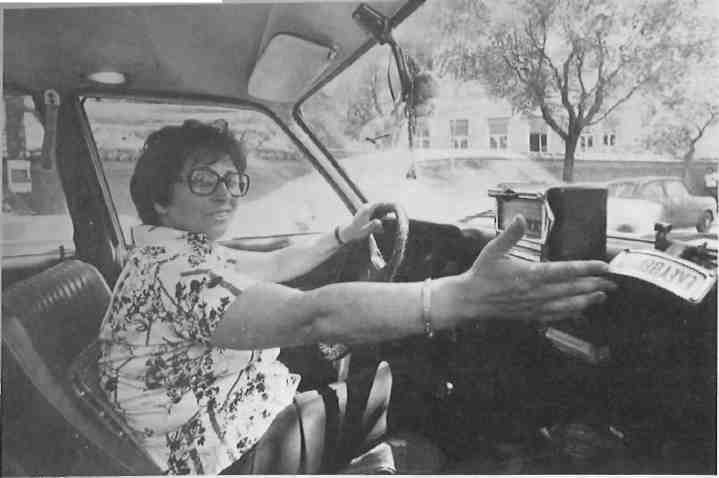

We had started off together in the morning. During the five hours I spent sitting next to her in the front seat of her cab, she remained impervious to affronts from other drivers, never forcing her way in front of another car, violating a traffic regulation, or involving herself in rude exchanges. One hundred and seventy kilometres later, we had completed a non-stop tour that covered the city as far as Glyfada. All the while she remained composed, and courteous, conveying the impression that driving a taxi was a difficult but not unrealistic profession for a woman.

I come from a village and my parents were illiterate, but I try to be civilized. People can be very rude. They lose their tempers for no reason and begin shouting. Sometimes they say things like, “What can you expect from a woman taxi driver? ” or ” Go home and wash your dishes, Kyria mou. ” Why do they talk like that? Oddly enough, women are the worst! Greek women are still bound to their past… when they were slaves to men.’

That morning, she did not feel her best, she explained: ‘The fellow who drives the cab in the afternoons went through a red light and they have taken away his license… for only a few days, I hope. Meanwhile I must work Ionger hours.’

As she drove along, Kyria Hariklia opened the glove compartment and handed me a pocket-size photograph album. ‘There I am with my husband, ‘ she indicated with quick glances, her eyes only momentarily leaving the road. ‘We love each other very much in my family.’ Her husband lives in the United States where he has a car repair service in Stamford, Connecticut. He had already settled there when they married. She joined him for a while but the climate was ‘too damp and humid’ and so she returned to Greece. ‘We are very close and we miss each other very much. We spend a lot of money on long distance calls and he comes to Greece often. He wants to sell everything and settle here in Athens. We have a nice time when we’re together. We go out a lot to tavernas. That’s the reason I put on weight recently,’ she added with a touch of coquetry. ‘When he is not here I usually return home after work and stay there.’ Pointing once more to the photographs she adds: ‘There I am with my brother and his children. We are five brothers and sisters. We lost our mother a year and a half ago. My father lives with one of my sisters here in Athens. Sometimes after work I visit him… I look after him like a baby.’

A young man hailed the cab and asked politely to be driven to Exarhia. Ί only know the address. Do you think you can find it? Kyria Hariklia, it seems, knows every avenue, street and path in Athens, Piraeus and the suburbs. ‘Don’t worry son,’ she assured him maternally. Til get you there.’ Turning to me she explained: Ί always speak to my clients in a friendly way to put them at ease, and usually they respond.’

Kyria Hariklia was in her early twenties when she came to Athens from her village. Not long after she applied for a driver’ s license. The examiner at the registry suggested she apply for a professional license as well. Ί liked the idea and that was it,’ she explains succinctly, reaching under her seat for her bag from which she retrieved a yellowed newspaper clipping. A young woman beamed out from above the caption: ‘The first woman professional driver.’ The Minister of Communications, Vranopoulos, the article announced, had issued on July 23, 1962 a professional driver’s permit for the first time to a woman. She had been received by the minister in his office. He had wished her good luck in her new profession.

The minister, Kyria Hariklia noted with a smile of amusement, had warned her that it was an unusual profession for a woman and that she would encounter many difficulties. For the first five years Kyria Hariklia worked as a driver at a factory. The union at first was in a dilemma, unable to decide on her starting salary. ‘After some months they decided to give me the same salary as a man. It was then 1860 drachmas per month.’ Later she doubled as a saleswoman and driver at another factory. Ί drove throughout Attica and the whole of Greece, ‘ she says. Eventually she acquired a share in the taxi. ‘In those days they gave licenses only to people who had driven professionally for several years and met certain other requirements. I kept both jobs, working half a day at the factory and the other half driving the taxi. It was· exhausting. When I married, my husband didn’t want me to work that much. My ex-boss in the factory still calls me and promises me high pay if I go back. But I won’ t. I prefer my taxi for the time being. ‘

Kyria Hariklia owns only half of the taxi she drives. She pays a monthly rent to the other half-owner in exchange for which she manages the taxi herself, a not uncommon practice in Athens. She hires another driver for the afternoons and nights. Ί start very early in the morning, five or six, and work until early in the afternoon. Then the other driver takes over.’

‘The things that I hear behind the wheel, or see through the rear-view mirror make me more sensitive and tolerant of people. Among the things I object to are couples who enter my taxi and begin necking. They know I see them through the rear-view mirror but they continue. And you know,’ she added, ‘women are much more aggressive than men. ‘ She illustrated with an anecdote: The other day a couple got into my car and immediately the woman started teasing the man in a suggestive way. I told her to stop but she didn’t pay attention. So I stopped the car suddenly and turned to her: “Either you stop it or get out of my taxi, “I said. She asked me if I were an old maid and I told her that if she really wanted to know, I have a husband who is a real man. Her escort at this point told her to calm down, that her behaviour was embarassing.’

Ahead of us standing at the curb were two women, each holding a young child in her arms and several parcels. As we pulled over one of them called through the window:

‘We are going to Nea Philadelphia.’

‘Okay. Get in, ladies,’ she replied, ‘put your parcels in the back.’

‘When there is an old person I will get out and help them,’ she explained. ‘And I sometimes escort them up to their doors.’ A few blocks further on another woman asked to be taken in the same direction. Ί take them as long as the first client doesn’t object,’ she said. The second fare got out last and paid the full fare. ‘If they are willing why should I refuse’, she commented philosophically.

We were circling Omonia Square and as we moved slowly forward drivers and passengers around us stared into the cab surprised to see a woman behind the wheel of a taxi. Some of them winked or called out remarks. Kyria Hariklia concentrated on her driving, ignoring the attention.

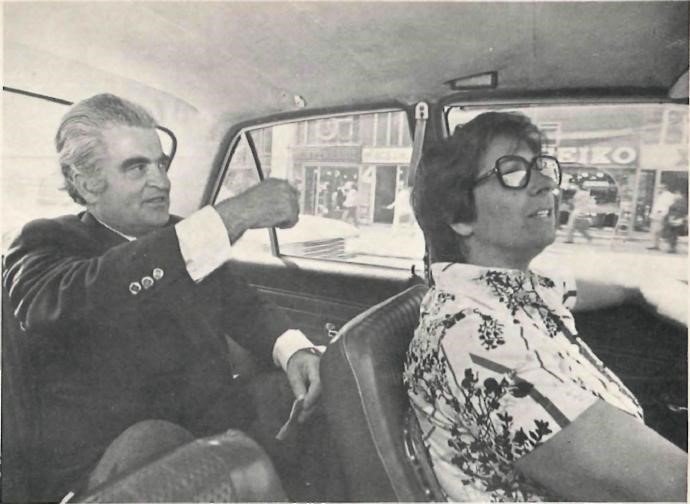

We stopped for a couple standing at a corner. The woman wore a short-skirted, vivid-green dress, and stiffly-set hair sparkling with lacquer. She held a bouquet of gladiolas. The man was stout but well-groomed and sombrely dressed. They got in and he sat with his legs firmly apart, his arms extended and clutching the seat in front of him. He gave their destination.

A few minutes later Kyria Hariklia turned to the woman cheerfully: ‘Well, dear, you must be going to a party! Before the woman could answer the man leaned heavily toward the front seat: ‘If you knew where we were going you wouldn’t mention a party,’ came his reply. Quickly putting two and two together, Kyria Hariklia asked: ‘Was he at least old?’

Changing the subject I questioned her about the impending taxi strike. I won’ t participate,’ she explained, ‘but I won’t be a strike-breaker either. Anyway, it will be an opportunity to leave my car in the shop for repairs.’

‘To which union do you belong?’ asked the man who, as it turned out, was a colleague.

‘You know,’ she told him, ‘you came at the right time. The lady next to me…’

‘ … is a journalist,’ said the man, completing the sentence as he looked at my pad and pencil. He began to speak rapidly. ‘ Listen, madame. One of the reasons we will strike is because the traffic police punish us when we don’t stop to pick up a fare. Ί ask you frankly,’ he continued, ‘Where and when can taxi drivers go to do what everyone else does several times a day? That’s one of our main problems. After only a few years behind the wheel we become neurotic, we suffer from our back, from our stomach and heart.’

After they got out Kyria Hariklia explained that she does not socialize with her fellow taxi drivers. *A female colleague once invited me to join her for coffee in Halandri but I refused. If I had accepted,’ she reasoned,’ then a male colleague might ask me to a game of cards with him, and so on. I don’t have any friends among the other drivers. They use very crude language and I can’t stand it. That’s why I never stop at the taxi stands. I prefer to drive constantly.’

At the corner of Voukourestiou and Stadiou two American tourists signaled. They wanted to see the Plaka before returning to their hotel.

Ί never go to the Plaka, even in the daytime. I don’t like what it has become. But let’s give them a little tour…’ When we dropped them off at their hotel the metre showed forty-seven drachmas. They handed her fifty and told her with a smile to keep the change. ‘Foreigners are stingy,’ she observed. ‘You should see the way they count their drachmas.’

It was lunch time but Kyria Hariklia said she never stops to eat while working. ‘Besides, where can you eat in the middle of the city? Have you ever eaten escargots with oregano?’ she continued. ‘You boil the snails, remove them from their shells, clean them, and then mix them with chopped fresh oregano and whole egg. Roll them with flour and fry them. It is a delicacy,’ Athens’ first woman taxi driver told me.

A few minutes later she dropped me off at my house. I was exhausted, but Kyria Hariklia drove off, as fresh and animated as when we had started out.