Indeed, the island of Paros was, like all the Cyclades, poor, depopulated, and subject to the ravages of invasion and piracy. And yet Justinian, who reigned from A.D. 527-565, elected to have built on this island one of the largest and most beautiful churches — and now one of the oldest — in this obscure part of his empire.

Its origins shrouded in myth, the church of Ekatonapyliani was built during a time when historians, dazzled by the glitter and intrigues of Constantinople, had little interest in the provinces. According to legend, when St. Helena (the mother of Emperor Constantine the Great who reigned from 306-337 and was the first Roman emperor to be converted to Christianity) passed through Paros on her way to Jerusalem to find the True Cross, she vowed to have a church erected on the island upon her return journey. Unfortunately, she died enroute, and it was left to Justinian, two centuries later, to order the completion of her vow. Justinian assigned the task to his favourite architect, Isidore, who had not long before completed Constantinople’s magnificent Aghia Sophia at the Emperor’s command. Isidore duly sketched a general plan and delegated his skilled apprentice Ignatius, a native of Paros, to execute it. Ignatius chose a site for the church close to the harbour of Paros’ main town, Paroikia, where a Roman building had once stood. (A mosaic from the original building which was found a metre below the present church floor is now in the Paroikia museum.) Early Christian buildings were frequently built on the sites of ancient buildings. The old locations had been carefully chosen, and retained an aura of sacredness.

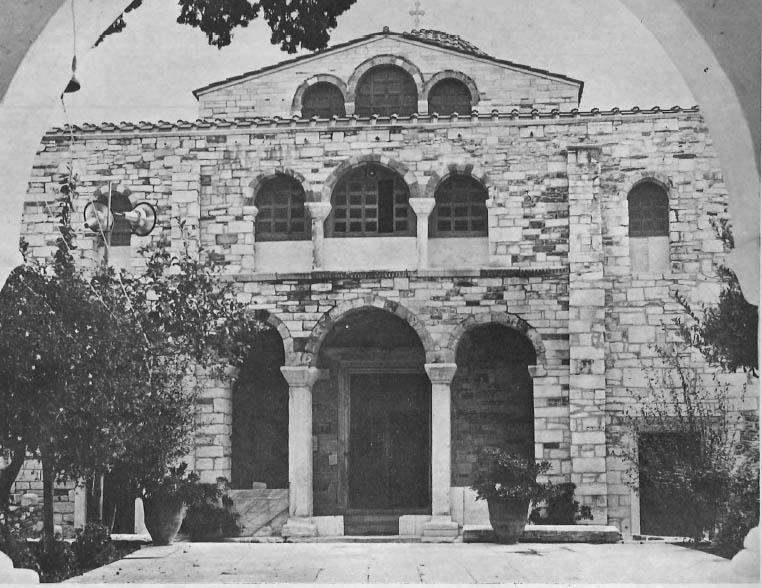

Having selected his site, Ignatius proceeded to build the little church of Aghios Nikolaos. This was later incorporated into the larger structure. Satisfied with his work, he then built the Great Church on an ambitious scale. When Isidore voyaged to Paros to inspect his pupil’s work, he was more than impressed: in fact, he was so envious that he lured Ignatius to the roof to discuss a supposed flaw, only to vengefully push him off. The disciple clutched desperately at his master’s robes, and they both plunged to their deaths. Portraits of master and apprentice were carved on the bases of the columns that flank the main entrance to the church. Both are depicted kneeling: the master on the left grasps his beard to express penitence for this crime, while the apprentice, on the right, holds his fractured head.

The name Ekatonapyliani means ‘hundred doors’. A modern story claims that only ninety-nine doors have been discovered and that the one hundredth will be found when Constantinople is returned to the Greeks, Originally the church seems to have been called katapoliani, or ‘below the town’ — an accurate enough designation in the days before Paroikia’s construction boom — from which the present name was derived. Parians call it simply the Panaghia, or Virgin Mary, and are proud of its great antiquity, for it has been continually in use for nearly 1500 years. Catholics worshipped there during the Venetian era when the left side was reserved for the Orthodox. Comte Noandel, French ambassador to the Sultan, Hugue Crevliers, the inspiration for Byron’s Corsair, Marco Sanudo, Duke of Naxos after 1207, and St. Arsenios, the modern patron of Paros, prayed here.

The building underwent numerous changes in the turbulent and tragic centuries that followed its construction, but it has largely retained its original form. The church is constructed in three main parts, the most important of which is the Great Church built about 550. The church of Aghios Nikolaos was built somewhat earlier. The third main element, the Baptistery, a basilica abutting the Great Church, was built circa 600, although all these dates are highly uncertain.

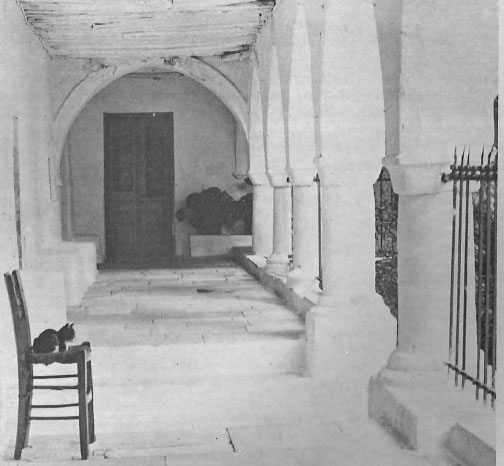

The exterior of the church has an architectural splendour which is sometimes difficult to properly appreciate today, for in the seventeenth century a two-storied enclosure was built around three sides. It contains arcades and monks’ cells which served as a fortification in times of insecurity. The seventeenth century witnessed much monastic activity on Paros; many of its present churches and monasteries were constructed then, including the monastery of Longovardhas, still the most flourishing in the Cyclades. Today, to get a good overall view of the church it is necessary to climb the hill behind it. On entering the courtyard, the immediate impression is one of size. Several bells are hung from a huge, handsome tree in the centre of the courtyard. The original bell tower collapsed in an earthquake in 1738 during the festival of St. Spyridon. The garden is abundantly planted with tangerine trees, rosebushes, and jasmine, their fragrance mingling with the waft of incense from within the church. Marble blocks are strewn all about, remains from both Classical and Byzantine structures. In fact, it is obvious that a great deal of the church’s stone has been reused. Old photographs show the church as entirely whitewashed; only recently has the original stone been uncovered.

Some of the antiquities discovered here are in the museum, others are still in the underground crypt or in the second century necropolis behind the church. A number of interesting Roman period sarcophagi remain just outside the walls. An earthquake in the tenth century necessitated a great deal of reconstruction, and little differentiation was made between old and new building materials, so that the antiquarian will find the church a veritable museum.

The interior of the Great Church is noble and impressive, despite the installation of neon lights (mysterious play of light and shadow is crucial to Byzantine architecture). Those of us lucky enough to have seen the church by candlelight will not forget its subtle and majestic sense of space. Richly decorated with a brilliant array of tombs, lecterns, icons, censors, stalls, it remains the island’s main centre of worship. The Church is cruciform in plan, though not a perfect Greek cross, being one of a number of churches which marks the transition from basilica to Greek cross. The nave at first seems quite short: the imposing dome tends to make the space below seem squarer than it is. Resting on pendentives decorated with frescoes of angels, it was originally hemispherical; a restoration (after an earthquake in 1507) resulted in its present shape, which from the outside, is octagonal.

The ancient columns of the aisle arcades have beautiful capitals of a quasilonic type, carved from Parian marble, which in Byzantine times as well as Classical was considered the finest in the world. (The sale of marble made Paros rich in the Classical era.) The capitals have a raised design of foliage over a cross and egg-and-dart moulding in very low relief.

The elaborate and handsome altar screen — the iconostasis — bears many fine old icons, of which the three largest are the most significant: the Pantocrator, the Dormition of the Virgin, and the Virgin. The latter is an object of great veneration, as its strings of valuable votives testify. All three icons are encased in silver donated by Nikolaos Mavroghennis in 1788.(Mavroghennis went to Constantinople to seek his fortune and finally became Governor of Moldavia. He was beheaded by the furious Sultan when, after a heroic defense, his army was overwhelmed during the Russo-Turkish war of 1787). Petros Mavroghennis, Nikolaos’s father, repaired the church in 1758 in return for two fields, which he promptly redonated to the church in exchange for masses to be said for his soul.

The Holy Table, in the altar area behind the iconostasis, is a large lucent slab of white marble, supported by two fragments of ancient columns. Originally Classical, it was adapted by Byzantine craftsmen for ecclesiastical use. The canopy over the Holy Table, with its exquisitely carved capitals, is made of an unusual stone. On the walls of the altar area are frescoes which were discovered under the centuries overlay of whitewash when the church was restored in 1962. They depict twenty-four scenes from the life of the Virgin in a primitive, vigorous style.

A door to the rear left of the church leads to the church of Aghios Nikolaos. The monolithic fluted columns here are of late Roman type and hewn from Parian marble; they no doubt came from the late Roman structure which preceded the church. The bishop’s throne, in fact, is supported by a Classical pedestal.

Among the tombs in the Great Church is that of St. Theoktisti, patroness of Paros. According to legend she was a beautiful maiden from Lesbos captured by the Saracen corsair Niseri in the ninth century. When the boat stopped at Paros to take in water she asked for a moment’s privacy to relieve herself, and cleverly made her escape. She thereafter lived on fruits and insects on the island until discovered by a hunter whom she asked for communion wafers. When he returned to give them to her, she was dead. He cut off the saintly virgin’s hand to keep as a relic, and prepared to depart. But despite the strong winds, his boat refused to move, and did so only after he returned the hand to her body. St. Theoktisti’s relics are today carried in a procession on November ninth.

To the right of the Great Church a stairway leads to the galleries. Behind the stairway is the entrance to the Baptistery, dedicated, of course, to St. John the Baptist. In the narthex of the Baptistery are some scattered marbles of Roman date, and a Roman column. The central doorway has beautiful ornamentation, but the main feature of the Baptistery is the sunken cruciform font, which has a frieze of Greek crosses and part of a column in the centre.

The Parians are very proud of their famous old church, and know its history. It is specially venerated on August fifteenth, the dormition of the Virgin, when Paros is second only to Tinos in popularity. The holy icon of the Virgin is carried through streets jammed with Athenians, Parians, and tourists. Perhaps the church’s most poetic moments come during Easter, when on Good Friday rose petals are dropped from the dome, or after midnight, on Easter Sunday, when the candles of the faithful again light uo the ancient stone