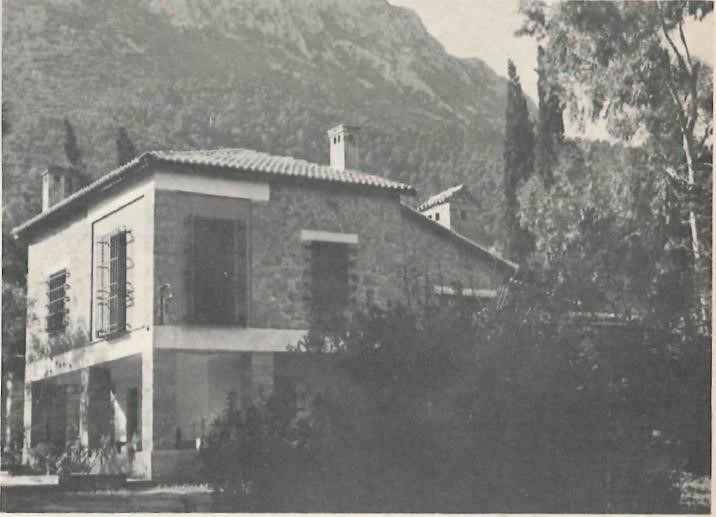

AT THE entrance to the village of Avlona stands the Zygomala Museum, its cypress, oleanders and pines silhouetted against the sky. A wide walk leads through a long, narrow garden to a pi-shaped structure built around a small courtyard. The wing to the right is two-storied. It was here that Loukia Zygomala spent the last years of her life arranging her collection of priceless works of embroidery which are today found in the adjoining single-storied museum.

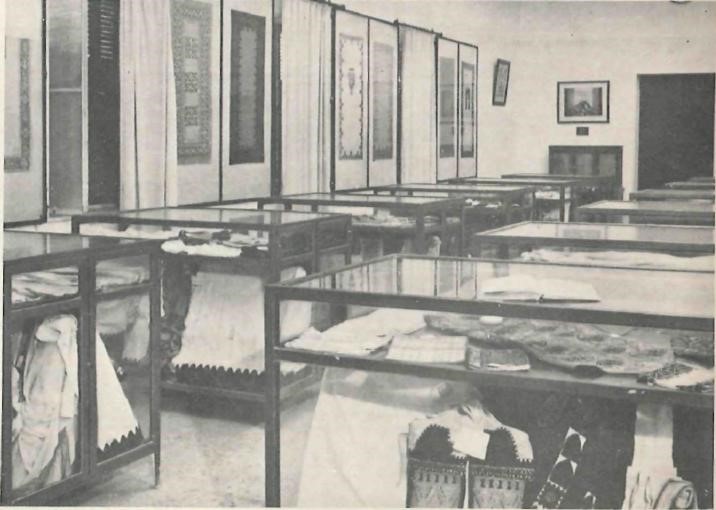

The custodian who lives in a cottage on the property fetched the key and opened the door for us. We stepped out of the sunlight into the dimly lit interior. The atmosphere inside was as cold and heavy as that of a long-sealed crypt. Sunlight rarely penetrates the two large rooms of the museum. The windows, facing north, are there to display the heavily embroidered curtains and do not allow the light of day to pass through. In a sectioned-off area of the first room, a mannequin, dressed in a lavish costume, sits before a frame, caught forever in the act of embroidering. Next to her is a four-poster bed, its canopy and bedspread richly embellished with needlework. Beyond this bedroom scene is a small parlour arrangement — the sofa and chairs, cushions, lampshades, and drapery elaborately and brightly covered with intricate embroidery. Two over sized dolls, every detail of their dress decorated with networks of coloured thread, guard the entrance to the next room. A life-size mannequin in a traditional folk costume of Attica gazes at case upon case of dense displays of delicate embroideries painstakingly wrought long ago by many busy hands. Despite the splendour of this immense still life, it is peculiarly lifeless. The museum is almost forgotten, a sad tribute to Loukia Zygomala, a rare, unselfish individual, who devoted her energy, her talent and her fortune to preserving and perpetuating the art of traditional Attic embroidery.

Beyond the two rooms of the museum is a door leading into the family study. From here a staircase leads to the living quarters above. The study has been closed for fifteen years but we are given permission to enter the room.

Cobwebs fall away as the door is swung open to reveal a scene reminiscent of Great Expectations. Photographs, paintings and memorabilia cover the walls; a uniform, a torn flag, weapons and medals, are neatly arranged, the few mementoes of Loukia Zygomala’s son. Born Loukia Balanou, she was the daughter of a prominent, late-nineteenth-century Athenian lawyer, Aristidis Balanos, a member of a notable Ioannian family. Her sister, Anna, married Spyros Lambrou who was to become Prime Minister of Greece. Their daughter, Lina, Loukia’s niece, was to marry another Greek Prime Minister, Panagis Tsaldaris, and was to become the first woman cabinet minister in this country and one of the first woman delegates to the United Nations. Loukia married Antonios Zygomalas, a member of another illustrious family that traced its roots back to Byzantine times. He was a lawyer and politician who represented Attica and Boeotia in parliament and became Minister of Education in 1904 during Theodore Deliyannis’s administration. It was during that time that he acquired from the noted industrialist and philanthropist, Andreas Sygros (after whom Sygrou Avenue is named), a large tract of land in the area around Avlona (the final payments for which were made many years later from the proceeds of the sale of his wife’s house in Athens) where they built their summer home which is today the museum. Antonios Zygomalas parcelled out the bulk of his land to the peasants in the area who repaid him in small installments.

It was during the years of her husband’s involvement with the welfare of his constituents that Loukia Zygomala became interested in the Attic embroidery that adorned the traditional dress worn by the women of the area. At first only an object of passing interest, it became her lifetime occupation after the death, in 1914, of her son, a young officer stationed in Epirus during the first Balkan campaign.

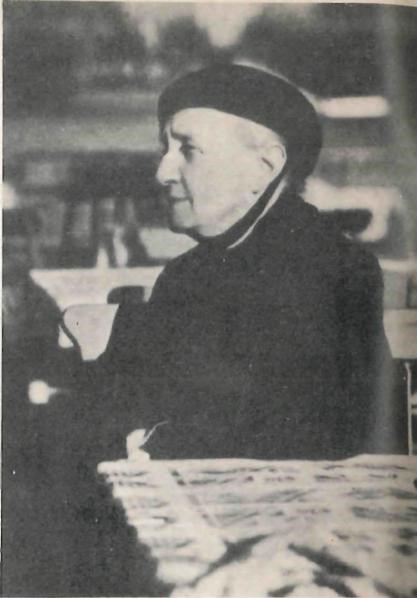

Today Loukia Zygomala’s famous niece, Lina Tsaldaris — the dowager of the Greek political scene — recalls that tragic event. Her Aunt Loukia and her Uncle Antonios frequently travelled from Athens to her parents summer retreat in Kifissia. In the afternoon they would sit in the park not far from the railroad station. Her father, Spyros Lambrou, rarely joined them on these occasions, preoccupied as he was with his work. It was therefore with some alarm that she saw her father approaching them one afternoon in the park, knowing immediately that only an emergency would have brought him there. Reluctantly, he informed them that Andreas Zygomalas had been killed. A few minutes before, Mrs. Tsaldaris recalls, her aunt had been telling them that she had received a letter from Andreas saying he would be coming home to spend a few days with them.

Devastated by this loss, Loukia Zygomala transferred her energies to the women in Attica, many of whose husbands and sons were at the battle front during the years of protracted warfare. As a focus for her endeavours she turned her attention to the traditional embroidery of the area.

In 1915 she began to organize centres in the province of Attica — in the villages of Salesi, Varnava, Marathon, Menidi, Liosia, Liopesi, Koropi, Markopoulos, Kalivia and Keratea. To this project and the shop she would eventually open on Voulis Street in Athens, she gave the name ‘Attiki’. In time more than fifteen thousand women were to participate.

Although village women were familiar with embroidery techniques, they sewed unsystematically, either at whim or of necessity. Under the aegis of Loukia Zygomala, young girls were trained in the highest skills, using the traditional motifs which she incorporated into patterns to produce new, intricate, and extraordinarily beautiful designs that combined spontaneity and finesse. The shop in Athens was established to provide an outlet for their work. It included a workshop for the more talented young girls from the villages. In time a textile mill and a carpet weaving shop in Menidi were established.

Although all the materials were largely financed by Loukia Zygomala, the proceeds from the sale of the crafts went to the women who trained and worked at these schools. The extra income provided them with incentive and encouragement, particularly during the harsh years of 1916-23 when their men were at the front during the Balkan Wars.

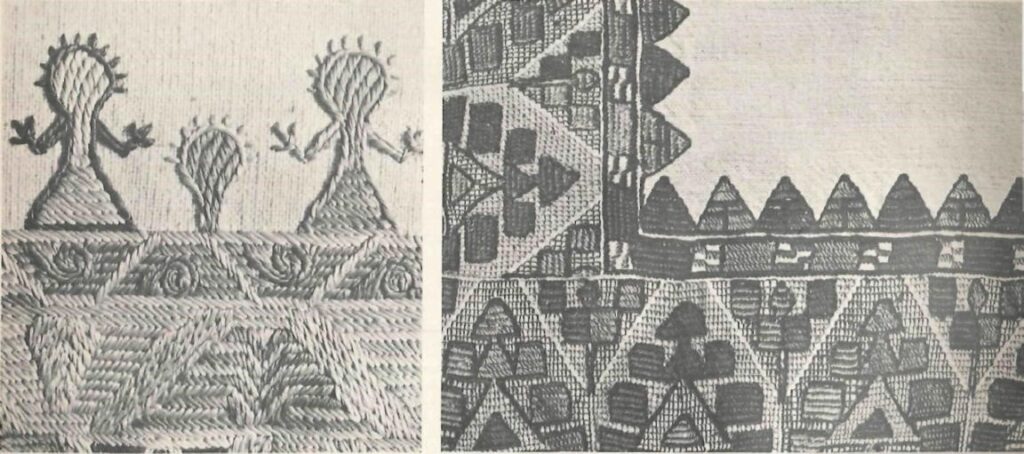

The folk costumes of the province of Attica which were the inspiration for Loukia Zygomala’s designs consisted of three main types: the everyday dress, the bridal dress of the well-to-do, and the bridal dress of the poor. The everyday dress was worn for the first time by a young bride about a week after her wedding when she first assumed her role as a housewife, carrying water from the village fountain, or delivering frugal meals to her husband working in the fields. The bridal dress, which was passed from mother to daughter, was worn after the wedding on feast days until the birth of the first child. If there were several daughters, each was given a piece of the mother’s dress and eventually, by adding to this over the years, made her own gown. The bridal dress of the more affluent was referred to as the ‘Golden Dress’ because of its elaborate gold-threaded detail. The dress of the poor differed in that the gold strands were replaced by threads in eighteen different colours creating a less spectacular but perhaps more beautiful mosaic of colours that bordered the long skirt and the sleeves of the bodice — the tsakos.

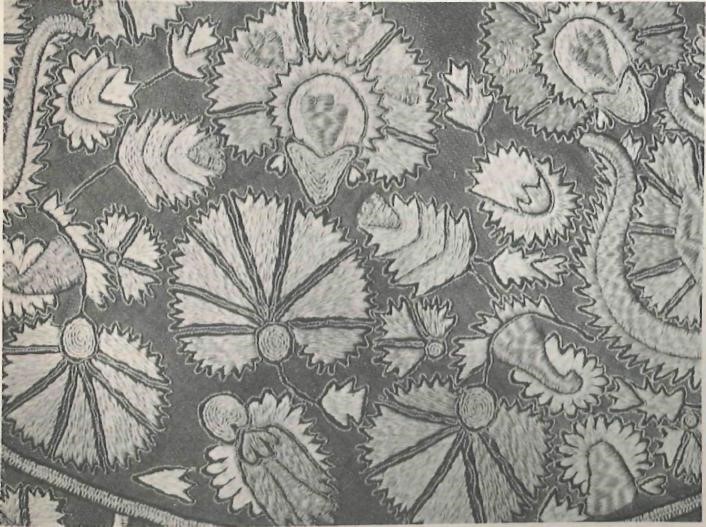

The motifs adapted by Loukia Zygomala, as well as the stitches and techniques used to produce the special effects of the embroideries, were meticulously analysed in Attiki, a book by the late Greek artist, Takis Loukidis (which is now, unfortunately, out of print but can be found in libraries). Loukidis notes that many of the designs can be traced to the archaic, Minoan and Byzantine periods. To these designs Loukia Zygomala added new details. Among the traditional flora and fauna can be found the odd frog or tiny bee and a myriad of other details that combine authenticity with a striking originality. She also added another dimension to the traditional art which may be seen today in contemporary handicrafts. Previously restricted to costumes and some decorative household items, under her guidance the traditional designs were applied to dresses and gowns of all types, children’s outfits, curtains, cushions, lampshades, bedspreads, couches and chairs.

In 1925 she was awarded the first prize at the Paris International Exposition of Modern Decorative and Industrial Arts. The critic of Le Figaro, describing the display which consisted of an entire apartment completely decorated with embroidered furniture, drapings and rugs from the Menidi workshop, noted:

‘Standing before these countless cushions that surround the beautiful, detailed and superbly embroidered rugs… one is astonished by the outstanding combinations… blues, rose colours, dark violet, flowers with the lustre of porcelain…’

Gradually as costs rose, the financial burden to Loukia Zygomala increased. In 1936 she was obliged to curtail her activities and to close the workshops and the shop in Athens. With the death of her husband in 1930, she had moved from her home in Athens and settled in her summer house in Avlona. Here she spent the last years of her life arranging all the items as they are seen today in the section of the house transformed into a museum, assisted by only Dimitris Papaconstantinou, the headmaster of the local elementary school. After her death in 1947, he personally looked after the museum during the remainder of his tenure in Avlona. Upon his retirement, he moved to Alexandroupolis in Northern Greece and the museum is now sadly neglected. Ά museum like this should be an example for generations to come,’ he said when I contacted him. ‘It must have devoted people to take care of it.’ The young teacher who was our escort noted, ‘Whenever the head of the school changes, we spend several days working hard to catalogue all the museum’s contents. Once in a while we spread naphtaleneto protect them. Some years ago one of the teachers spread it on top of the embroideries, which would have damaged them. We had to remove them and start from the beginning.’ Although in the past the school’s teachers volunteered their time to the museum, many now commute from Athens and are unable to. If enough public interest is shown, however, this unique collection may yet be saved. According to the terms of Loukia Zygomala’s will, the museum is under the auspices of the Ministry of Culture, run by a three-member committee composed of the Director of Fine Arts of the Ministry Of Culture, the supervisor of the area’s schools, and the headmaster of the elementary school in the village of Avlona. The little money that she left and the 100,000 drachma subsidy that the Ministry of Culture provides every year cover only the most fundamental necessities for the operation of the museum.

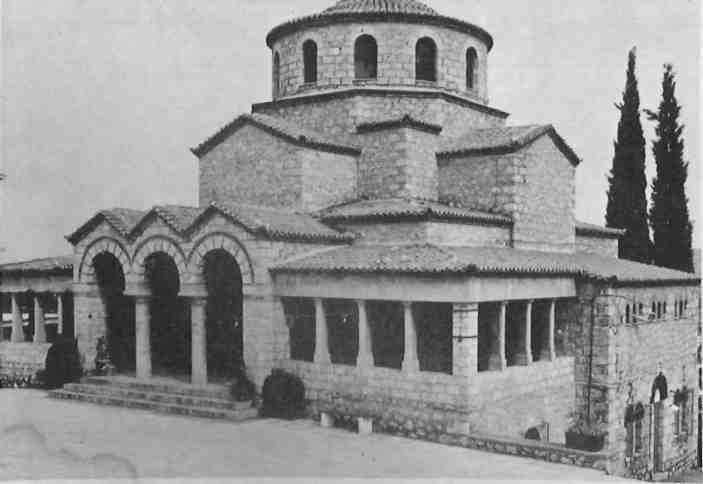

Leaving the museum, we drove over to the Church of Saints Anthony and Andrew built by Loukia Zygomala in 1938 in memory of her husband and son. Designed by Nicholas Zoumboulidis after the Church of the Saints Theodori in Mistra, its walls are covered by unusual pastel-coloured frescoes and icons executed by Takis Loukidis. Behind the altar are the crypts of the Zygomala family. Pater Vassilis Christophorou, one of the two Pater Vassilis who are the church’s priests, greeted us. A native of Avlona, he vividly remembers Loukia Zygomala who contributed so much to the village and its people.

Ί cannot forget the face of the Lady, or how kind she was to all of us.’ After so many years, he explained, he still refers to her as ‘The Lady’.