Photographs by Eugene Vanderpool

Kyrios Mytilineos was our escort and guide during a tour of Anafiotika on a sunny morning in February. He was born in the heart of the little colony clustered on the side of the Acropolis at the turn of the century. Although his name suggests that his ancestors came from Mytilene, they were from Santorini. He has the calmness of manner associated with islanders, however, and a remarkable physical endurance that amazed me during the three hours we spent climbing up and down steep steps, entering houses and churches, and talking to the people of Anafiotika.

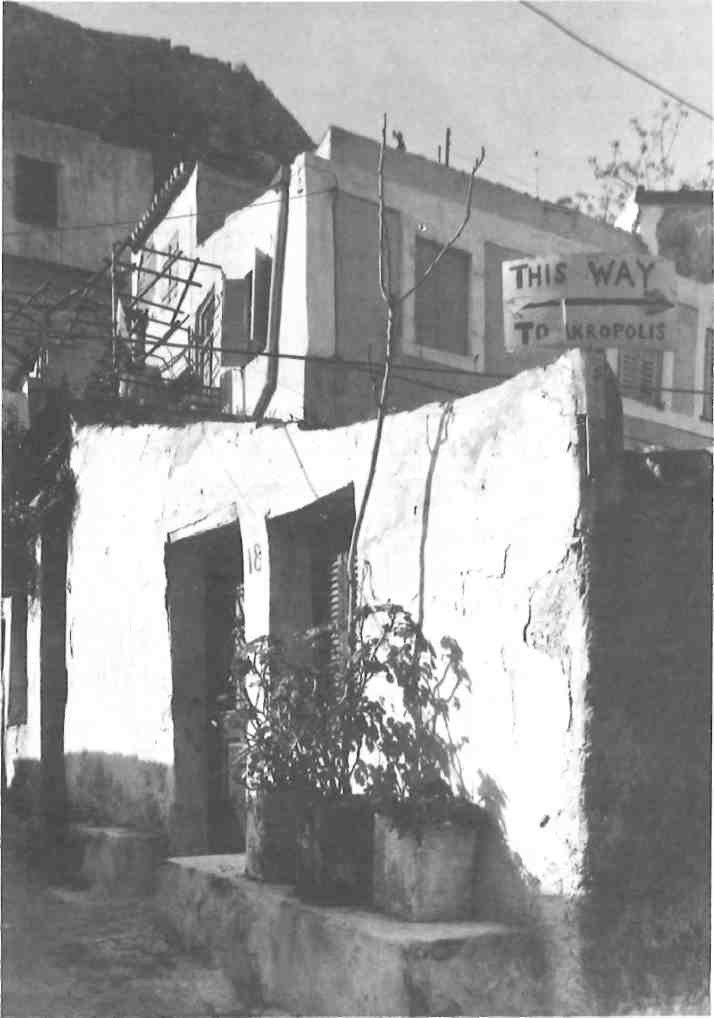

Anafiotika is actually a district of Plaka. It begins at the lovely Byzantine church of Saint Nicholas Ragavas, at the corner of Epiharmou and Prytaniou streets, immediately below the flag flying on top of the Acropolis. Mounting the steps to Anafiotika, one is greeted by the past and present living in harmony. There have been few ugly changes made. Its traditional appearance and ambience have been preserved, the tiny, vividly painted island houses seemingly stacked one upon the other. Kyrios Mytilineos indicated the stairs on Eretheos Street: “Down there was one of the two fountains where we drew water, our school, and the only bakery. Children took casseroles to school every day and after class filled them with a day’s portion for each member of the family at the food station subsidized by the government. A portion of meat with pasta cost one dekara. A portion of revithia and beans, twenty lepta.”

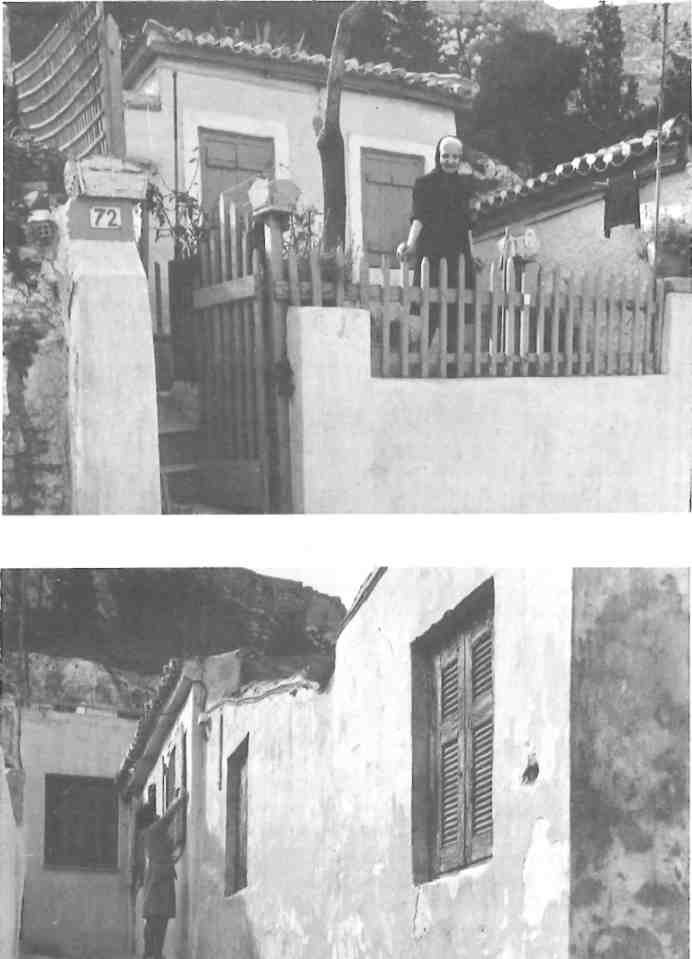

As the streets extend upwards in Anafiotika they narrow, becoming paths, once earth or pebbles, now cement, bearing no names. On the wall of each house and on the right side of the entrance there is usually a number to identify it. “One is in a labyrinth but, unlike Theseus, without a string to find one’s way out,” the local postman commented with a good-natured smile. The elderly people of the district, their faces tired but pleasant, greet you as they go about their daily chores. They are ready to answer your queries and recite legends about the first settlers. (The young people are not to be seen during the day; they work far away in the city or the outskirts.)

“Let me tell you the whole story and how Anafiotika came about,” said a middle-aged blond woman emerging from her little garden. She was wearing a plastic apron and holding a fork in her right hand. “When King Otto decided to build his palace, he asked some builders from Anafi to come and do it. You see they were and still are the best builders. When the palace was ready the master builder told the King that he was obliged to go back to his island because his sister was waiting for him there. You see, in those days the family was united. Not like now. But the King said to him: Ί want you to stay. Athens is now under construction and we need you. Choose a place that you like and I’ll give it to you.’ The Anafioti looked around and answered, There on the slope under the Acropolis — I want to build my house there. The steep ground reminds me of my island.’ You see, madame, that’s how we came here. Those who say we installed ourselves without permission are wrong. We settled here and then came the Law. But who makes the Law? Those who want to kick us out. You can find all these details in the encyclopedia.”

There are many versions of how the Anafiotes came to settle on the Acropolis. Another legend says that the islanders, known to be skilled builders, were brought here to repair the Acropolis’s ramparts and set up their homes near the work site. The probabilities are that the Anafiotes simply did what Greeks have done for thousands of years: build their homes on the Holy Hill despite official disapproval.

A natural citadel, the Acropolis has been the location of many settlements since prehistoric times including that of the Pelasgi, an ancient people believed by Athenians to have built the earliest fortifications. Around the seventh century B.C., however, the Acropolis had come to be considered sacred and private dwellings were removed. “No settlement or any kind of house will be allowed on the Black Rocks, on top of the Pelasgian’s place,” proclaimed the Delphic oracle. Nevertheless, when Athens was attacked during the Peloponnesian War in the fourth century B.C., its inhabitants abandoned their homes in the city and sought refuge on the precise spot on the northwest slope proscribed by the Oracle.

It continued to provide asylum during the many invasions throughout the city’s history. In 1821, during the War of Independence, Athenians rose up and took control of the city which they held for four years. Much building began in an orderly fashion, resulting in an unusually picturesque city where monuments from all periods of antiquity and the Middle Ages stood alongside Islamic buildings depicting the city’s unbroken history in relief. According to an 1824 census, the number of houses in Athens had reached sixteen hundred and there were just over nine thousand inhabitants. The city itself was divided into thirty-five districts, each with its own church from which they took their names. Greece’s independence was declared in 1825 but in 1826 the Turks returned once more and laid siege to the city, recapturing the Acropolis which remained in their hands until March of 1833. A few months later, Athens was declared the capital of modern Greece. Prior to this, the capital had been located in Nafplion.

As Athenians returned from refuges in Aegina and Salamis, they were greeted by ruins. Monuments were damaged, houses were heaps of rubble. Arriving on the wave of neo-classical architecture then sweeping Europe, many of the world’s foremost architects converged on the source of their inspiration to draw up elaborate plans for a carefully laid out modern Athens with wide avenues, and to design public and private dwellings such as the Old Palace (now the Parliament), the University, the Academy, the National Library, and Benaki Museum, landmarks of today. Before the plans for the city itself could be implemented, however, they were abandoned in the face of compelling human needs: the citizens of Athens had already rebuilt their homes or erected new ones, and it was too late.

Meanwhile settlers continued to arrive from other parts of Greece and abroad, the Greeks in search of a better life, the foreigners either on pilgrimages to the Athens of Pericles, or to establish themselves in the expanding capital which enjoyed a mild climate and held promise of economic opportunities. The building boom continued drawing workers from other parts of the country, among them the Anafiotes from Anafi, the tiny Cycladic island only seven miles long, located near Santorini.

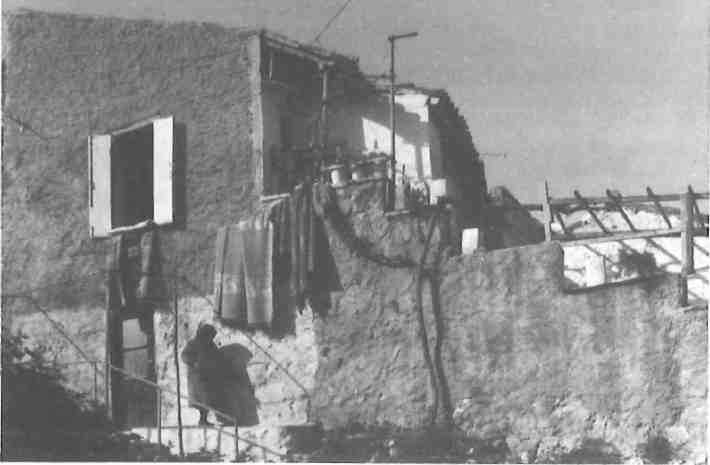

As buildings went up and the city grew, the Acropolis was again declared off limits to dwellings. Nevertheless, one morning, as the sun rose over Athens, it revealed two small houses clinging to the rock on the northern side of the hill behind the Byzantine church of Saint Nicholas Ragava. Using materials collected from the streets, two young Anafiotes, a carpenter by the name of Giorgos Damigos, and a builder by the name of Markos Sigalas, had solved their families’ housing problem by pooling their skills and erecting their tiny houses during the night. Their nocturnal activities had not gone entirely unnoticed, but in response to questions from the curious, they had replied, “Oh, we are just building a church.” By the time the authorities became aware of the houses on the forbidden site, they were already occupied by the two large families who could not very well be evicted. As more and more Anafiotes arrived in Athens to find work, more and more solved their housing problems by following the example of their compatriots. During the day they would covertly begin filling holes in the ground, levelling the rocks, and digging the soil. By nightfall the young and old, men and women, would join in to make certain that dawn would find the houses erected and roofed. Once this was accomplished, the police would not evict them. One attached to the other, faithful to the architecture of Anafi where the roofs are without tiles but terraced with a thick layer of a special mixture of soil which hardens like cement, the houses sprang up overnight as the little colony climbed up the slopes of the Acropolis. The Anafiotes were not preoccupied by history or questions of archaeology. Their concern was to shelter their families without paying rent.

In time they decided it was necessary to give their little settlement a name. Some said it should be named Nihtohori — the Night Village — alluding to the circumstances under which it was built. The opinion of the original settlers prevailed, however, and the little community was called Anafiotika, the place of the Anafiotes. The name was appropriate for another reason as well. Anafenome means sudden appearance, and Anafi, the name of their island, means “revealing”. According to myth as the Argonauts returned from Colchis with the Golden Fleece, they were overtaken by a great storm and were lost in pitch darkness. Jason appealed to the god Apollo who responded with a flash of light from his bow revealing the little island of Anafi where the Argonauts were able to beach their ship.

IN mid-nineteenth century, Athens was a thirsty city and there was no question of bringing water to the top of Anafiotika. The inhabitants used to go down the rocky paths, fill their stamnes or wooden barrels with water from fountains located near two churches, load them on their shoulders, and climb back up the steep path too narrow for beasts of burden. Andreas Karkavitsas, a writer who lived from 1860 to 1922, described the labyrinthian paths leading to the primitive but complete households whose people were happy having found a spot of their own. That their homes leaned on a Pelasgian rock, that their potted geraniums perched on a piece of marble from the Holy Hill or that their laundry was spread to dry in the ancient theatre of Dionysios did not seem inappropriate.

The view from Anafiotika was once superb. Athens was spread out at its feet. In the distance the horizon was a green and pastoral scene of plains, forests, fields, monasteries and churches, embraced by the three mountains that cradle Athens: Mount Parnis, Mount Penteli and Hymettos. Immediately below was the Old Palace surrounded by the neoclassical houses of the wealthy fanning out from Constitution Square.

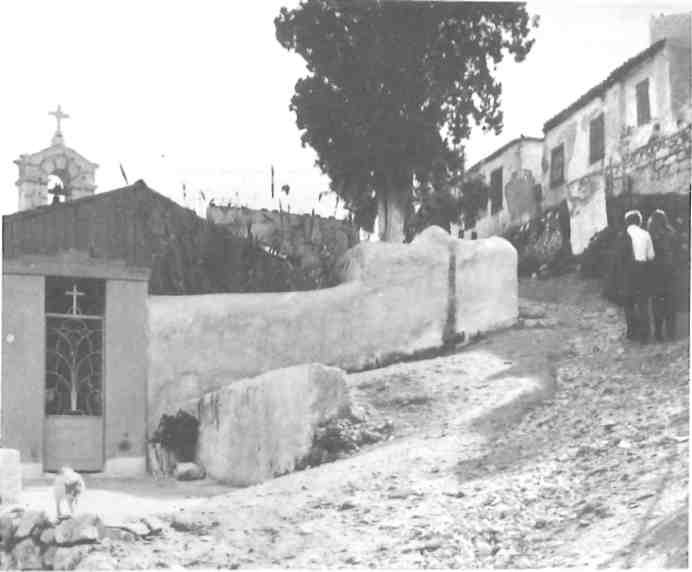

For some time the Anafiotes attended the nearby church of Saint Nicholas of Ragava but soon they wanted their own church. In 1845 they restored the eighteenth century Saint Simeon’s and later, as their numbers grew, built Saint George’s. The triangle formed by the three churches marks off the area of Anafiotika. Saint Simeon’s is their most beloved church, however, because it houses the icon of Panagia Kalamiotissa—the Madonna of the Reeds. The Panagia Kalamiotissa, found on a hill hidden among reeds on Anafi, is credited with many miracles. Her feast day on September 8 is to this day marked by a major celebration during which money is collected to be sent to the church built on the island of Anafi in her honour.

As years passed, many of the first settlers sold or rented their tiny houses, returned to their island, or moved to different areas of Greece. Anafiotika has gradually become an international colony inhabited by Greeks from other parts of the country, refugees from Asia Minor and foreigners. Artists and intellectuals have settled here, happy to find a calm, romantic and picturesque corner near the city but removed from the noise, under the Acropolis.

A DARK cloud now hangs over the peace and charm of Anafiotika. It is within the archaeological zone and considerations of antiquity take precedence over its history which spans a century and a half. For many years now the Anafiotes have lived in uncertainty, faced with the possibility of expropriation by official decree (which accounts for the neglect of many of the houses). Archaeologists, architects, and urban planners are divided: there are those who attach the most importance to everything that dates from classical times. There are those who believe that antiquity does not lay sole claim to our inheritance, that the architecture of the last centuries, although humble by comparison to the ancient monuments, has its worth, another link in the story of modern Greece. To the latter, Anafiotika is a vestige of the Athens that was struggling to emerge as an independent, modern city, and represents a period between the marble of the past and the cement of today, a blend of materials which include the human soul. They believe it should be preserved.

Conversation kept returning to this subject as we made our way around Anafiotika—but only after we had dispelled the Anafiotes’s suspicions that I was from the archaeological service. “Don’t worry,” Mr. Mytilineos reassured an old woman, “I was born here more than seventy years ago and even then they were saying that Anafiotika would be torn down. I’m sure it won’t happen.” The grey-clad, grey-haired woman standing on the stairway looked at us with wet eyes. She made a gesture of despair. “I’m eighty years old and came here as a child from Aigio, Peloponissos. I was married in this house. Where should I go now? I want them to let me die here in peace.”

“She is right,” continued another woman from her doorway next to a multi-coloured carpet hung on a clothesline. “They tell us that we live in a primitive way. Why primitive? We have everything: electricity, television, water, plumbing, telephones, everything we need. We are about seventy families here. Where should we go?”

It is like the chorus of an ancient tragedy. The despair and bitterness grew as we climbed higher up the rocky slope of the Acropolis. Mrs. Maroula came out of her house. “I bought my home for eight hundred drachmas with the money I earned working during my youth in a rich family, not far from the Palace. I have all the papers. I’m old now and love this place. I can’t move. Do you see that beautiful house up there, with the blue railings on the terrace?” she continued. “Go and ask for the key of the church of Saint Simeon, from Kyria Vasso. On February the third we celebrate his name day.”

We knocked at Kyria Vasso’s door. A joyful woman with a scarf covering her curly hair appeared. “Good morning,” said Kyrios Mytilineos. “Are you the daughter of Poussetos?”

“Yes,” said the woman, “who are you?”

“I’m the son of Kyra Pagona and Kyr Aggelis, remember? I was born here,” and he pointed to a nearby ochre-yellow house.

“Oh, yes I remember, but very vaguely.”

“How old are you?” asked Kyrios Mytilineos disarmingly.

“I’m fifty-five,” said Kyria Vasso with a touch of coquetry.

I interrupted these exchanges to ask for the key. “I cannot go out,” she said decidedly. “I’m sick, I had the flu and I cannot go out.”

“Very well, but it’s a pity because we would like to go and see the church,” I said.

The word pity — krima — upset her. Immediately she could be heard closing windows and doors and in a few minutes she came out pleasantly angry, with the key to the church. If the source of her distress was that we would not be able to see the church, or that she would be thought inhospitable, I could not tell. “Krima,” she murmured.

“Why krima?’ and started to make her way along an extremely tortuous path with Kyrios Mytilineos and me following.

At the corner a woman was whitewashing the edge of the path. “Tin preparing it for the name day of Saint Simeon,” she explained. We found ourselves in front of a small white church with a modern metal door painted light blue. To the right there is a piece of marble with the inscription: “Saint Simeon of Anafeon, 1774”. Blood-coloured geraniums stand nearby in metal containers. She opened the door and we entered a square courtyard sheltered by a wooden roof. Above the entrance another sign reads: “This church was restored in 1845”.

Other women arrived with bouquets of flowers: camellias, iris, mimosa. “We will decorate the icon of Saint Simeon with them and hang little flags in the yard,” explained one of them. Inside the church smelled of cleanliness and incense. To the right of the altar stands the icon of Panagia Kalamiotissa. The Madonna is surrounded by a cloud of tulle, white linen flowers, and laces. Kyria Vasso made the sign of the cross. “Look at this. I have decorated her like a bride. Every Anafiotissa that marries here in Athens brings me something from her bridal gown to place on the icon. You must come on the eighth of September. There will be officials and all Anafiotes come. We gather money and send it to Her Grace on the island. Years ago, in my father’s time we used to have a big fair, with music — our music — and many people. Now everyone who visits Anafiotika comes to see me. My house has become a meeting place. Don’t forget, I’m a grandmother.”

“You must consider yourself the mayor of Anafiotika,” I told her. Mrs. Vasso laughed with self satisfaction. Her father, who came from Anafi at the age of five, kept one of the two tavernas of Anafiotika, next door to their house. It is now closed. On its exterior an immense vase of flowers has been painted. The second taverna, Vlahos’s, now run by a son, is on the next street. It is a tall makeshift building with tourist-attracting decorations. The proprietor, the neighbours note approvingly, respects the serenity of the area. The inevitable modern music is played but he keeps the sound low.

“During summer months,” says an Anafioti, “we cannot go to church sometimes because we cannot sleep at night. The noise from Plaka coming up is so intrusive and constant. Drunk people climb up here in the dawn hours and knock on our doors. We suffer very much with all that. We don’t want those Greeks and foreigners who made Plaka a brothel.”

Continuing up, we heard, emerging from an .open window, the bittersweet song of a woman. She came out of her house to feed a group of well-nourished cats of which there are many in the area.

“You see,” she said, after a warm good-morning, “our houses are old and cats are absolutely necessary. My song? You like it? I’m from Amorgos and it reminds me of its beaches.”

Along the paths there are arrows showing the way to the top of the Acropolis. We followed these and found ourselves at the last of the houses. Two old women sat on a low wall near a row of half-ruined houses. One of them showed us a notice from the Ministry of Culture notifying them to evacuate their houses. They had known for months that this was inevitable, that their houses were to make way for a road to be built around the Acropolis, they had been told, but they could not accept it. Now they must leave. The older, a bent-over, tiny-handful of black clothes, wiped her eyes and said, “I was born in this house and it is here that I gave birth to my two children. Where shall we go? I’m alone.” “Why don’t you go to your children?” I asked. She replied: “They have large families, you see, and I don’t want to be a burden to them.”

The other woman complained about apartment buildings. “How can I live in a flat? I once stayed in one where my daughter lives. Everybody left in the morning and I was alone. There was nobody to speak to. I went to the church. I didn’t know anyone. I sat there alone like a dried up stump. Here, I see the sky, my friends, my flowers, the things I’m used to since my childhood. Why do they want to build a road around the Acropolis?”

All the families are facing their personal problems and dramas: the children will have to change school in the middle of the year, a mother whose paralyzed daughter is in a wheelchair will have to fend in some new place; the young girl whose house was to have been her dowry. “With the money they give us, what can we buy nowadays. Life is so expensive,” said a man.

We began to wind our way down and came to the whitewashed church dedicated to Saint George who for the moment is guarding this part of Anafiotika from the advancing dragon. Mr. Mytilineos recalls the game he used to play as a child around the huge rocks that jut from between some of the houses. Above us, the flag on the Acropolis waved in the wind. Its colours were indistinguishable from the sky. Anafiotika was behind us.