Everything in that room seemed seductive. Surrounded by high, cobweb-laden wooden shelves, I would spend long intervals in a mild state of euphoria among the huge, metal vats where my grandparents stored olive oil, exploring the drawers of the lovely old pieces of furniture, and the musty baskets which held fragile blue and amber-coloured vases barely perceptible under layers of dust. A taciturn, yet lively communication existed between me and those relics of the past.

I have continued to be delighted by the mere touch of old things and some years ago I began to make visits to the flea markets of Monastiraki and Psiri — the oldest residential part of the city, located next to Monastiraki — and later, became a devotee of the Piraeus Flea Market, Ta Paliatzidika tou Pirea. Only the people of the area and a small circle of initiated Athenians were then aware of the existence of the Piraeus market. It is considerably smaller than the Athens Flea Market, covering, as it does, only one city block. Nevertheless, in relation to its size, it is well equipped with a good selection of old things ranging from furniture, china, copper and silver, to old pottery and objects rescued from now demolished, turn-of-the-century houses. The overall atmosphere is friendlier and the shopkeepers more affable and less commercially-minded than their Athens counterparts, generally managing to convey the impression that they are not after your money. Up to a few years ago, the prices were much lower than those in Monastiraki. Today there is an effort to imitate the capital, but the area remains remote, modest, less crowded, and relatively unknown. It is seldom visited by the majority of Athenians.

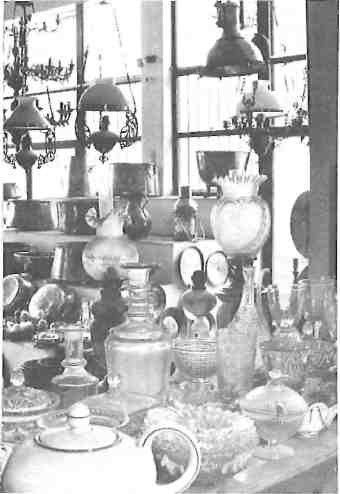

There are not more than six shops of special interest. Almost all of their owners are self taught ‘antiquaries’ who have taken over the enterprises from relatives or former employers. They have a warm look, a gentleness of manner, and a calm and occasionally pessimistic view of life and their trade. They love their business, however, and immediately discern whether you really care about the old things they have for sale, or are merely a chance visitor or curiosity-seeker. When an item draws one’s attention, it becomes, in my experience, the subject of a long, and generally successful process of bargaining.

This is expected, a way of life, a highly developed art to be enjoyed. One does not bargain merely to save money. One bargains because it allows for a longer chat and provides an opportunity to learn more about the object under discussion: where and when it was acquired and its time and place of origin. Bargaining over less-unusual or less-expensive items may lead to the exchange of true or imaginary stories, little innocent lies or deliberate deceptions, cunning manoeuvres and tactics, false surprises, disappointments or to-be-expected clever remarks. Usually the seller enjoys an encounter with a determined buyer whose bargaining can transform the transaction into an elaborate ritual.

The Piraeus Flea Market dates back to the beginning of the century. It was originally a market place located on Korai Square, opposite the Municipal Theatre of Piraeus (the Dimotiko Theatro tou Pirea, which has recently been renovated and restored to its former charm). After the exchange of populations with Turkey which followed the 1922 Asia Minor Disaster, many of the refugees who settled in Piraeus became shop owners. The market moved to Karaiskaki Square where there were two arcades, one devoted to vegetables and the other to second-hand goods and clothing, and scrap metal. Gradually the area changed character. Tiny shops selling old items sprung up, ladies of pleasure and their protector-sponsors appeared, as well as hashish dens (tekes) frequented by young labourers after a hard day’s work. In 1937 the area was destroyed by afire that successfully obliterated — old-timers of the area to this day note suspiciously — what the police had failed to wipe out with traditional methods.

The Occupation and the Civil War years that followed saw the reestablishment of the market in its present location. Wooden shanties were set up along the side of the train tracks, in lieu of shops. (Some of the buildings that now house the stores used to be ‘maisons de rendezvous’, among them the well-known establishment known as the House of Katingo.) Today, the oldest tenants of the area love to reminisce about that era and to present themselves as heroes of dramatic daily events. After so many years, it has assumed a legendary fame.

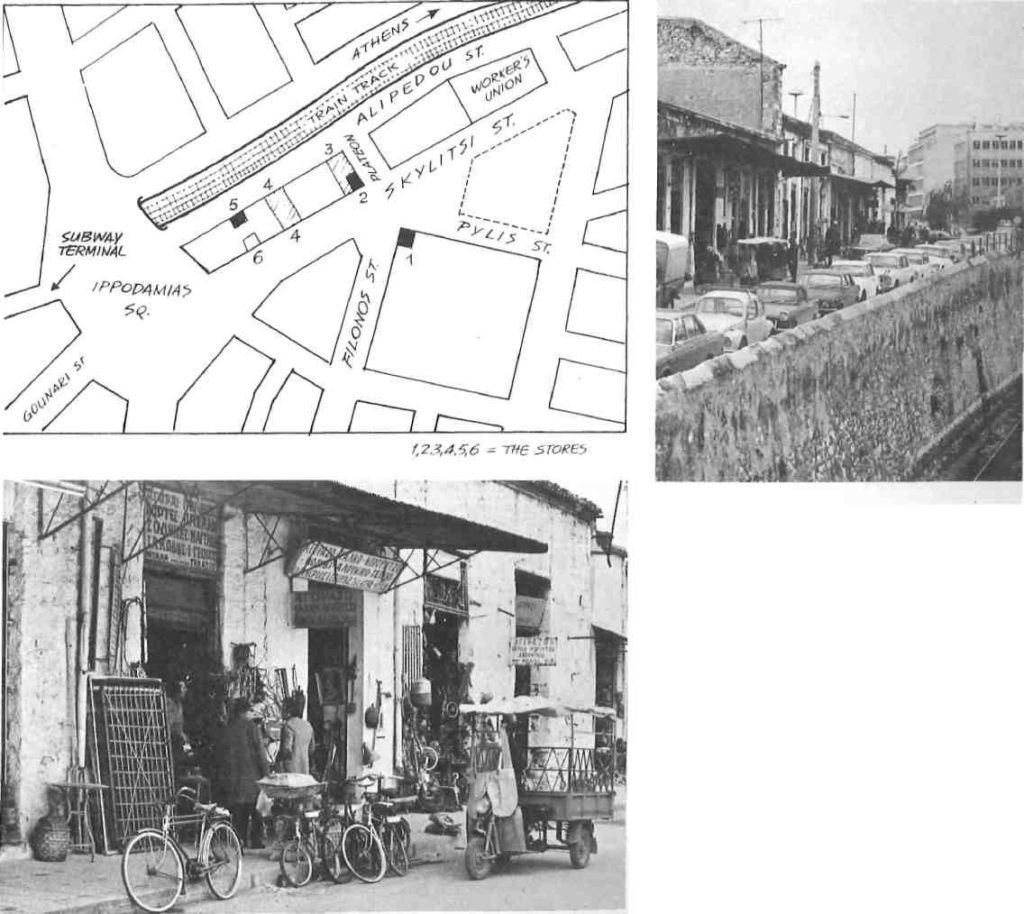

The advent in 1967 of the seven-year dictatorship found the Paliatzidika still housed in the shanties. One morning,’ recalls the little old man who is now the president of the Analipsis, ‘the mayor of Piraeus arrived with a bulldozer and in one day razed the shacks on Alipedou Street.’ (The Analipsis is the league of pedlars and owners of small shops selling used furniture and clothing. The owners of the principle stores belong to the League of Athens Antique Dealers.) In the general confusion, everyone salvaged what he could and the more fortunate moved into the ramshackle old shops located on the block bounded by Alipedou, Plateon, Skylitsi streets and Ippodamias Square. There they have remained, established in old, delapidated, two-storey buildings that might well have emerged from the pages of a Dickens novel.

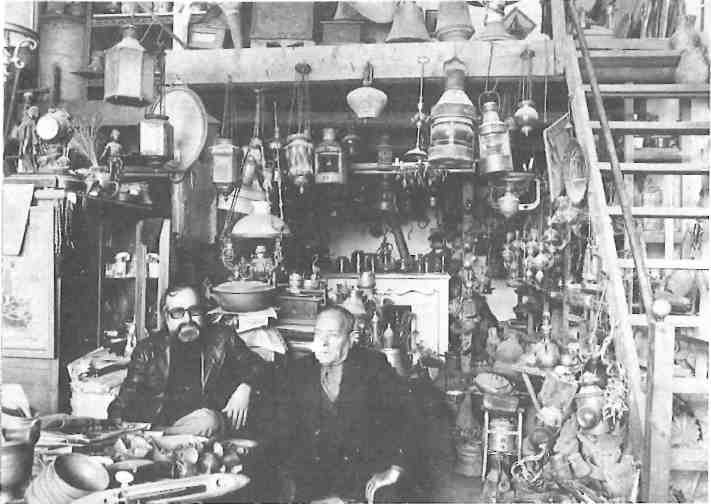

The sidewalk of Alipedou Street during the week is largely occupied by a dense row of cars parked bumper-to-bumper. On Sundays the area becomes an open-air bazaar, permission to do business on the Lord’s Day having been granted by the authorities some months ago. It is less crowded and poorer than the Sunday morning bazaar in Monastiraki. There are no stands to separate the sellers, only green lines painted on the sidewalks, and numbers on the street-side of the white-washed wall that blocks off the railroad tracks along Alipedou Street, to indicate the alloted spaces. Some pedlars set up tables or wooden racks to hold their wares, others merely spread newspapers on the sidewalk. Radios, cassette players, records, used clothes, small electrical appliances and cheap household items and decorations predominate. There are also the inevitable pedlars selling ‘tricks’ and vulgar, crudely-sexual items, their clientele men of all ages whose comments are bound to send most women scurrying. Another form of chatter is to be heard at the bird market in the next block where a rather large variety of our plumed friends sit in cages, waiting to be adopted. Although they now open on Sundays, the shopkeepers do not participate in the informal, open-air bazaar. They speak of the Sunday activity with condescension, conceding, however, that ‘it is good for them’ — meaning the pedlars — even though it brings more people to the area. ‘Some of their clientele also visit our stores but mostly they come to window-shop. We get very little business from them.’

When Τ visited Ta Paliatzidika tou Phea in December, it was a chilly, gloomy morning. I was accompanied by photographer Eugene Vanderpool whose presence brought out a more intimate and, paradoxically, less professional side of my shopkeeper friends. Others seemed to transfer roles: we were the merchants and they the merchandise. Some were reluctant to be photographed, however.

Our first port of call was the tiny store at the corner of Filonos and Pylis streets, the only one not located on the block. It is filled with all kinds of objects. An assemblage of furniture is cluttered over with a wide assortment of things all of which, in turn, are crowded by beautiful, old, porcelain coal-oil lamps, hanging from the ceiling and almost touching the other items on display, leaving only two, narrow paths through which one may walk.

Ί took over the shop some years ago from a relative of mine,’ the young proprietess, Mrs. Moudaki, says in a calm persuasive voice. ‘My love for antiques led me to read about them. I learned and expanded my merchandise. I have a regular Athenian clientele and supply many antique shops in Kolonaki.’ The lamps, known in Greece as nisiotikes — island style — are from the Aegean and Ionian islands, she explains, but were made in France, Austria, Great Britain and other parts of Europe and brought to Greece by sea captains to decorate their houses. They are easily converted to electricity. Most in demand today, however, is old jewelry from Northern Greece. Copper and bronze remain popular, and ecclesiastical items and Greek folk paintings have become fashionable. Fashion, she observes, governs what merchandise the dealers stock.

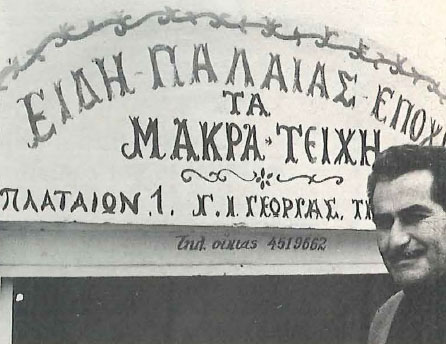

Taking our leave, we crossed Skylitsi Street diagonally and turned into Plateon where the entrance to the basement corner-store is marked by an elaborate sign reading Ta Makra Tihi – The Long Walls. The interesting merchandise to be found here is only one of the reasons to visit it. The others are to meet and chat with its sympatico owner, Kyrios Yiorgos Yiorgas, and to see a section of the ancient Long Walls built in the fifth century B.C. by the Athenians to safeguard their access to the port of Piraeus, which now forms one of the walls of the store itself. Kyrios Yiorgos seems to be a part of the premises. Were it not for talk of his family (he has two daughters, the eldest of whom ‘loves antiques’ and will study archaeology) one would suppose that he spends his entire life in his store. It was past noon. In response to a wink from Yiorgos, a waiter from across the way brought some most welcome ouzos — the cold was becoming bitter. If Kyrios Yiorgos likes you, he will show you his merchandise in between sips of ouzo or coffee. He inherited the shop from his father with whom he had worked since his youth but gradually, over the years, he changed the merchandise. He now specializes in kaseles (wooden chests) from mainland Greece and the islands. Some of the covers are decorated on the inside with primitive paintings which more-often-than-not show steamboats sailing the Turkish flag. He also has a great collection of folk-crafted wood and ceramics for everyday household use: vedoures (wooden butter churners used by shepherds); biskinia (wood or metal cradles); pitharia in all sizes (ceramic urns used by our ancestors to store liquids); and stoneware, marbles, bronze and copper from all parts of Greece.

‘Tell me what you want, madam, and I shall get it for you,’ he says with a pleasant voice. ‘Unfortunately antiques are scarce and difficult to locate, but sometimes business is slow and we send some of our things to be sold in Monastiraki.’

As Kyrios Yiorgos spoke, standing with us on the sidewalk, a pale-faced man was carrying old, wooden muskets from his basement shop and loading them on to a trikiklo parked in front of the door. ‘You see him?’ he asked. ‘In our profession there are three kinds of merchants.’ The first, he explains, are the gyrologi — pedlars who wander about and collect their merchandise in the neighbourhoods. The second are the kalderimidzides — (kalderimi — cobblestoned road) who sell at street corners. ‘We belong to a third group. We sell only real antiques.’

We entered Kyrios Yiorgos’s crowded shop and made our way cautiously to its inner recesses where part of a circular wall, constructed of huge pieces of stone, is illuminated by a special lamp hanging from the ceiling. ‘That’s a part of the Long Wall,’ he explains proudly, Ί discovered it while digging to enlarge my store.’ He has since uncovered it. As we left, Kyrios Yiorgos allowed us to photograph him at the top of the stairway that leads down to his store. From the ouzeri across the street came his friends’ remarks: ‘Go ahead Yiorgos, we’ll see you on television.’

Next door to Yiorgos’s shop are two steps leading up to Pantazis’s, a spacious store which begins on street level at the corner of Skylitsi Street, over Kyrios Yiorgos’s premises, and extends along the entire length of Plateon. Everything, from the large selection of icons, to furniture, lamps, paintings, chinaware, copper, bronze, crystal, and silver is carefully set out, numbered, and neatly arranged with light from the huge bay window falling on the display. Although this organization is convenient, it does not contribute to the general atmosphere. Nevertheless, the shop is ‘the pride of the market’, as a young employee commented.

After a brief glance, we proceeded to a shop belonging to a family from Crete, the Kalarhakides. We were greeted with a warm smile by the young, dark-haired and dark-eyed daughter of one of the owners. The store is very old and since it covers the width of Plateon Street, it has two entrances, the one on Alipedou Street, the other on Skylitsi. The girl guided us through the various rooms which house so many goods, including bric-a-brac in all styles and from most periods, that it seems unlikely that the owners themselves are aware of the existence of each item. Such is the reigning disorder. Two shaky wooden staircases lead to the rickety gallery above. An immense table is covered with embroideries and other handiworks. Old crocheted spreads, remnants of folk costumes and ecclesiastic gowns cover the walls. A collection of old wedding dresses is in a corner. There is a wide selection ot mats, doilies, runners and antimacassars, as well as old, Turkish hand-embroidered guest towels (tsevredes).The girl opens some drawers and shows me the most precious of their embroideries. ‘We have somethin0 for all requirements,’ she adds, commenting on the price range. ‘Now that I am engaged, from time to time I take one of them for my own home.’

We returned to Alipedou Street where an immense and rather grotesque, snow-white statue of Pallas

Athena, the ancient Greek Goddess of Wisdom, stands on the sidewalk before the entrance to the shop. ‘It was given to me when an old hotel next to the customs house was demolished,’ one of the owners who had just arrived informs us. ‘It is ceramic but unfortunately somebody painted it white. The Hilton Hotel asked me to rent it to them,’ he claims, ‘but I won’t. I love it too much.’ He is clearly proud of his rather morose work of art. On the pavement in front of some stores, little fires had been lit and the store owners gathered round to warm themselves.

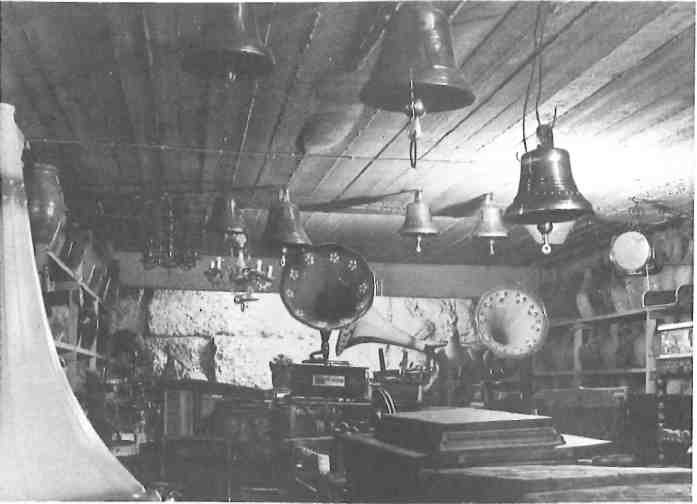

Nikos’s shop, a little further down the street, is primarily known for the fact that Nikos is from the Mani. ‘Nikos the Maniatis’ is young, dark, and bearded — and usually in the company of a friend. It seems as if the only reason he is in his shop is to receive visitors. We begin to chat and after a few seconds he orders two double ouzos. His little desk is piled with mounds of items which in turn are covered with a multitude of things. He deals mainly in copper, bronze and silverware, but every inch of this high-ceilinged shop, and its little gallery, is covered with layers of dust, much as though the shop had been closed for years and years and no one had set foot in it.

‘To be an antique dealer is just as easy as to be anything else. Whether you sell antiques or chestnuts, it’s the same thing,’ Nikos the Maniatis observes. ‘You just start.’ He became a dealer by chance, he laughingly explains. ‘My best clients are Greeks. Americans come and look. Many buy anything just so long as it is big. My dream is that when I am old I will retire to my village in the Mani and spend the rest of my life there.’ As we left, Nikos was greeting other friends who had come to call. We walked around the corner to Ippodamias Square where there are little shops selling inexpensive merchandise, waiting for their special clients.

Returning to Skylitsi Street, we stopped at the last store on our visit: the shop of Antonia and her brother. A square, high-ceilinged store, it has few but interesting objects: lamps, furniture, and folk art. A curly-headed young man polishing an old gun salutes us, his eyes rivetted to the ground. Ί don’t know if you may take photographs,’ he says. ‘My employers aren’t here. Anyway, if you want to take any, it’s to make money out of it.’

It was growing late. The freezing rain was chilling our faces. The flames burning on Alipedou Street danced in the wind.