He carried a camera and moved among the crowds inviting people to have their children photographed with ‘St. Basil’— a stout fellow, also dressed as a Santa Claus, sitting on a makeshift sled drawn by two papier-mache reindeer. To Dimitri Tselos, who was born in the Peloponissos at the turn of the century, it was clear that a strange fusion of St. Nicholas and St. Basil had taken place in his native land. Thus it happened that during his second Fulbright grant in Greece, the art historian decided to trace the evolution through the centuries of the various images of St. Nicholas, the customs associated with Christmas and the amalgamation and ‘repatriation’ of two saints from the eastern Mediterranean…

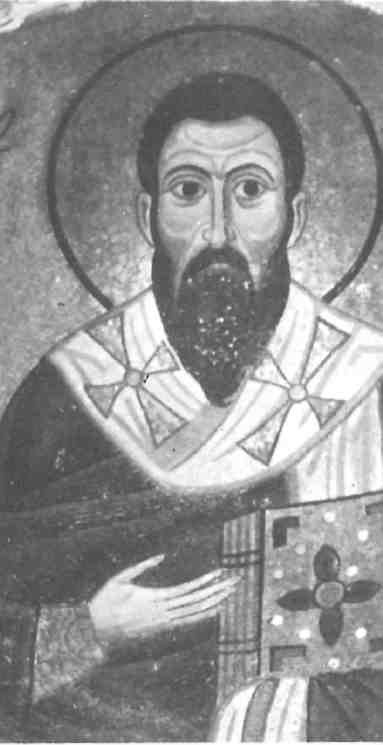

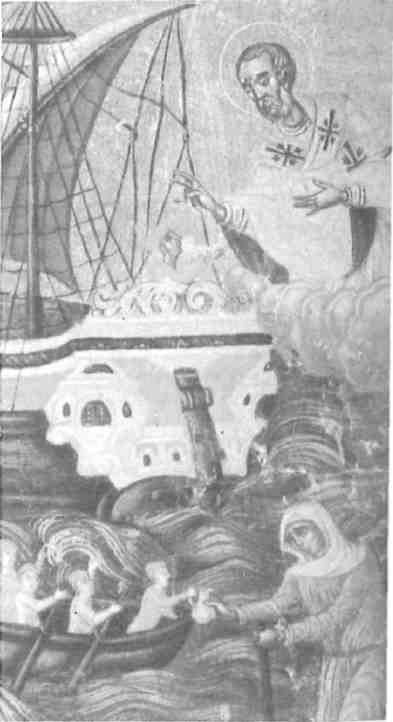

The conception of St. Nicholas or St. Basil as Santa Claus would have been unheard of in Greece before the Second World War. Here, as in southern Italy, St. Nicholas was worshiped as a patron of the men who ply the seven seas. Practically every vessel carried an icon of this saint who was always represented in his episcopal garments. Nor was St. Nicholas associated with gift-giving as he was in other parts of Europe. Indeed, there was no gift-giving saint in Greece until recent times when St. Nicholas or Santa Claus became confused with Agios Vasilis – Saint Basil the Great – one of the four fathers of the Greek Church. The reasons for this confusion of identities are due to the ancient Roman custom of the King’s Cake on New Year’s Day from which the Vasilopitais descended and, partly, in the comparatively recent American folklore which led to the development and diffusion of the meaning of Santa Claus.

According to tradition, St. Nicholas was the most universally loved saint in Europe for centuries. Born in Patara, Lycia in the southwest corner of Asia Minor, he became Bishop of Myra in the same region during the reign of Diocletian and died in the fourth century during the reign of Constantine the Great. His importance is affirmed by the fact that Justinian erected a church in Constantinople in honour of him and St. Priscus; his name began to appear in the catalogues of martyrs and saints in the ninth century when his feast day was established as December 6. Symeon Metaphrastes began to record events associated with his life during the tenth century. In 1807 his bones were stolen from Asia Minor, then controlled by Moslems, and taken for protection to Bari, Italy where a church was built to contain them. Thereafter his fame spread even more widely throughout western Europe, and from there to Russia where he became the patron saint of the country. In England, more than four hundred churches and chapels were built in his honour. On the continent he became the most popular of saints and more than three thousand churches were dedicated to him.

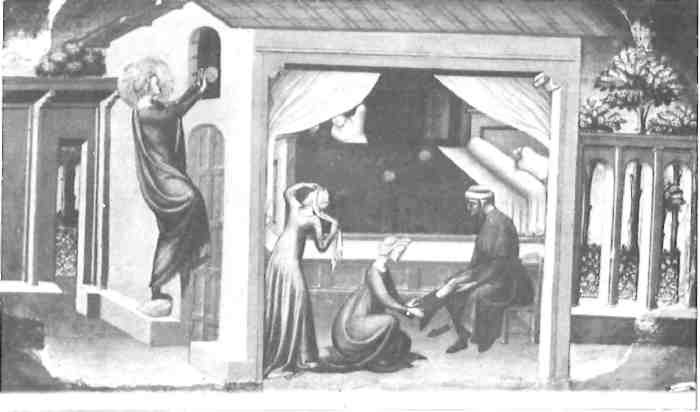

St. Nicholas’s image as protector of young people and children is no doubt ascribable to accounts of two incidents believed to have taken place during his life. The first is the story of the three dowerless maidens. The young St. Nicholas wanted to devote the fortune he had inherited to benefit humanity and to the greater glory of God. Learning of the plight of an impoverished nobleman who was neither able to support his daughters nor provide them with dowries and was therefore thinking of consigning them to a life of shame, St. Nicholas wrapped some gold in a cloth and threw it into the nobleman’s house during the night. He repeated this benevolent gesture twice and enabled the father to marry off his daughters. The story was frequently illustrated by Medieval and early Renaissance painters, especially in Florence and Siena.

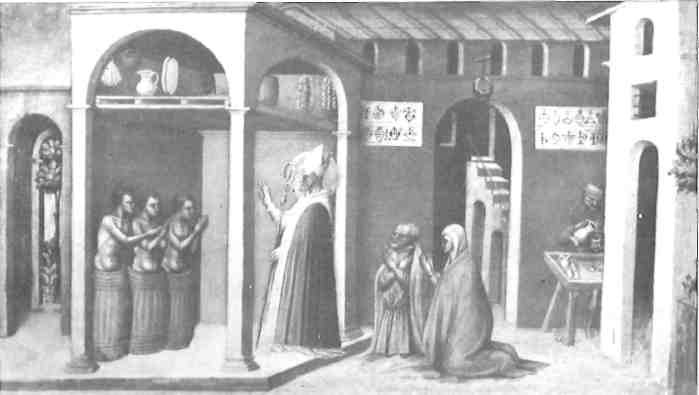

The second story concerns a miracle. Three young students on their way to study in Athens stopped at an inn near Myra where they were murdered and robbed by the innkeeper who then dismembered their bodies and hid them in three large vats. St. Nicholas, divining what had happened, went to the inn, reprimanded the murderer, and immediately brought the young scholars back to life by making the sign of the cross. This miracle was widely illustrated in Medieval and Renaissance art in France, England and Italy (but is unknown in Greek tradition). Although both the killing and the resurrection were sometimes depicted, in most works only the resurrected students and the saint were represented. In accordance with Medieval practise, Saint Nicholas as the ‘hero’ was depicted as disproportionately larger than the students who, in some cases, were so small that it gave rise to another variant of the miracle: that the victims were babies who had been dismembered by their impoverished parents, or by an innkeeper, to be sold as food.

These stories established St. Nicholas as the Patron Saint of the young and his gifts to the dowerless maidens may well have led to the tradition of his bringing gifts to children on his feast day. That such a convention had been established by the seventeenth century in parts of Europe can be inferred from the efforts of Protestant ministers at that time to discourage the worship of saints and to divert the gift-giving custom from December 6 to Christmas.

Their efforts were successful in some countries, but in Belgium and Holland gift-giving continued to be associated with St. Nicholas on December 6. On the eve of his feast day, St. Nicholas — visible, of course, only to the parents — dressed in his bishop’s robe with pastoral staff and mitre, was said to visit mansions, houses and cottages, inquiring about the behaviour of the children and leaving words of praise or warning. Before his return early on the following day, the children would set out wooden shoes, baskets, stockings, large white sheets or other receptacles in which they placed fodder for Nicholas’s horse. In the morning they would awake to find the room in general disarray indicating that St. Nicholas had been there. In the receptacles of the obedient and studious children, the fodder was replaced with sweets and playthings; in those of the bad children the fodder was untouched and in place of gifts would be rods for their punishment. Inevitably the gift-giving aspect of the tradition extended to grown-ups over the centuries.

Because of the association of Christmas with the Adoration of the Magi, it was logical that it would in time become the day of gift-giving in most Christian countries. The transfer of the custom to that day, however, had as tortuous a beginning as the determination of the birth date of Christ, about which no lasting decisions were made until the fourth century. Around the year 336 the Church of Rome singled out December 25 for the celebration of the Nativity. The date had originally been chosen by the Emperor Aurelian (undoubtedly under the influence of the Oriental cult of Mithraism) in A.D. 274 to celebrate the birthday of ‘The Unconquered Sun’ and to mark the winter solstice. (Although the Church’s choice was considered by some to have been tainted by paganism, it was undoubtedly an astute measure, asserting as it did Christianity’s preeminence over paganism shortly after Constantine the Great’s recognition of the new religion). The chief centres of the Eastern Church had meanwhile chosen to celebrate both the Nativity and the Baptism of Christ on January 6. However, by the year 380 they, too, adopted December 25 as the Feast of the Nativity but continued to observe the Baptism on January 6, as the day of the Epiphany. The Western Church, however, chose to celebrate the Adoration of the Magi on January 6 as the feast of the Epiphany and to relegate the Baptism to a mere mention on the calendar on the same date.

Pagan customs, albeit with Christian disguises, continued to survive despite the calculated efforts of the Churches to replace them with Christian ones. Many of the customs associated with Christmas and New Year celebrations can be traced to ancient festivals and specifically to the Roman Saturnalia. Similar to the even older Greek festival of Kronos, and, in ancient times, the merriest of festivals, the Saturnalia was celebrated from December 17 to 24. By the fourth century A.D. it had been extended and merged with the Kalends of January, New Year’s Day. (The kalends — or calends — were the first day of the months according to the Roman calender.) Houses were decorated with greenery and lights and gifts were exchanged. These practises were probably related to the ancient New Year’s day custom of presenting magistrates and other officials with luck-bringing twigs of greenery — cut from the sacred wood of the Goddess Strenia. (Other natural products such as figs, dates and honey were added to the gifts over the years and, eventually, medals or money, but the greenery retained an aspect of luck among the people.) Presents included wax candles, pottery images and dolls. A King’s Cake was prepared, which contained a bean or a coin; the recipient of the slice containing it became the Mock King — or Lord of Misrule.

If any connection exists between the Christmas fir tree and the pagan use of greenery is not certain. It is generally accepted that the Christmas tree cult developed in more contemporary times in Germany where the tradition is the oldest in Western Europe, and has been variously attributed to St. Boniface, St. Wilfrid or Martin Luther. The most credible and best documented explanation, however, is that it evolved from the Western European Mystery Plays, especially the Paradise Play dealing with The Creation and The Fall of Adam and Eve. From the eleventh century, it featured a fir tree hung with apples and symbolizing the Tree of Life or Knowledge. Mystery Plays were gradually eliminated from the churches. The decorated tree, however, was retained as a family custom for December 24, celebrated as the feast of Adam and Eve in many parts of Europe as early as the sixteenth century, The tree was, in time, symbolically decorated not only with apples (the Fruit of Sin), but also with the wafers of the Eucharist (the Fruit of Life), later replaced by cookies, and, in time, was hung with candles. The tree remained associated with Christmas Eve.

The exchange of gifts in the early Christian period continued to take place on New Year’s Day, after the pagan Roman custom, even though the practise was strongly condemned: St. Augustine called it ‘diabolical’, St. John Chrysostom ‘satanic extravagance’ and four Roman Catholic councils declared the practise to be a relic of ‘heathen ‘ superstition’. In Medieval times, the councils’ condemnations and the Protestant clergy’s opposition to gift-giving in those northwestern European countries where it had sprung up in relation to St. Nicholas on December 6, may have prompted the eventual transfer of the exchange of presents to Christmas. Be that as it may, when Christmas was finally adopted in many countries as the occasion for the exchange of gifts, the popular will was reluctant to give up St. Nicholas and made him an attendant of the Christ Child. As a bringer of gifts at Christmas, St. Nicholas has survived in various European countries as Pere Noel, Father Christmas, Joseph Clas, Kris Kringle, or Pelznicol (furry Nicholas). The Belgians and the Dutch, however, remaining devoted to their venerable tradition, added the Christmas tree to his saint’s day, and have continued, to this day, to exchange presents on December 6.

In other regions or countries the practise has continued on the first of the year but over the centuries the custom has lost its pagan meanings and acquired new and pleasant secular ones. On the Greek mainland gifts were up until recently exchanged on the first of the year without reference to a gift bringer. The connection of the Greek practise with the ancient Roman Saturnalia and Kalends practises (which the Greeks shared through their citizenship in the East Roman or Byzantine Empire) is confirmed by the singing of a New Year’s carol (Kalanda) and the tradition of the King’s Cake (Vasilopita), the special cake or bread baked for the first of New Year which contains a lucky coin.

The custom of the King’s Cake, however, and the Mock King has survived perhaps most clearly in France. There it was transferred to the feast of the Epiphany which in the Western Church, commemorates the Adoration of the Magi — that is, the coming of the Three Kings to Bethlehem. Hence the name of the cake came to be known as the Cakes of the Kings, Gateaux des Rois (and since the eve of Epiphany is the Twelfth Night, Twelfth Night Cake). The cake is made of special ingredients and varies from district to district. It is large enough to provide a piece for everyone in the family or party, and contains one fava or horse bean, or a coin. Whoever gets the lucky portion is immediately declared the ‘ruler’ of the occasion. The ruler then selects a partner (king or queen) and proceeds to perform a ‘follow the leader’ routine involving amusing or mildly embarrassing acts.

Just as the French Christianized the Mock King and the Cake of the Kings for the feast of Epiphany while they retained the Roman gift-giving custom on New Year’s Day, so too the Greeks transformed the pagan customs in their own special way. The cake of the Mock King, the Vasilopita, came to be known as St. Basil’s cake. Although the saint’s canonical feast day is celebrated on June 14 by the Greek Orthodox Church, the people’s folklore impulse placed it on the first of the year replacing the pagan Mock King with St. Basil whose name derives from a variant of the ancient Greek name for a king or master. That the name Vasilis derives from vasilias may have been a happy coincidence. Besides, his death on that first day of what had become the Christian year, provided St. Basil with a better claim to such distinction than a pagan Mock King.

One would have expected that here in Greece the gift-giving of the Roman’s New Year Kalends would also have been transferred to St. Basil, the only major Christian personality associated with New Year’s Day. This did not happen, however, until recent times, which is most surprising since Basil had left a substantial record of interest in the education of the young and the welfare of the underprivileged. Yet there is no visual record of either representations or impersonations of St. Basil as a gift-giving personality earlier than 1955. Sporadic reports from some Greeks that their New Year’s presents in the pre-war period were indeed brought by St. Basil notwithstanding, there is nothing of this practise recorded by the various folklorists of Greece (Megas, Romaios, et af) to suggest that it was widespread, even in Athens, before the Second World War. If gifts were brought to Greek children by St. Basil before that time it must have been limited to the families of Greeks who had travelled or lived in western European countries or in America and had brought back a custom associated with Pere Noel, or Santa Claus whose identity they may never have suspected to be that of St. Nicholas of Myra.

All the European customs were inevitably transferred by the immigrants to the New World. The benevolent St. Nicholas survived in America into the nineteenth century as he was traditionally represented in the garments of a dignified bishop performing various miracles or bringing gifts on either the eve of his December 6 festival, on Christmas Eve, or on New Year’s Day. His secularized conception as a short, plump, jolly, and elf-like figure speeding through the night on a sled drawn by eight reindeer and loaded with gifts for children is, however, a composite image which evolved in New York during the first half of the nineteenth century.

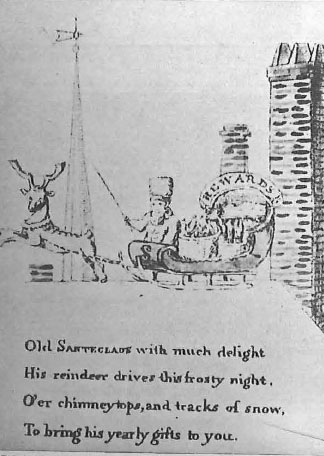

The earliest step in this transformation seems to have been taken by Washington Irving. In his whimsical satire Knickerbocker’s History of New York, published appropriately on December 6, 1809, Irving pokes gentle fun at the Dutch inhabitants of New Amsterdam and their activities in which their colony’s patron saint, St. Nicholas, seems frequently involved. He described St. Nicholas traveling over the roofs of the city in a wagon drawn by a horse and going down chimneys to deliver his presents on the eve of December 6. This was followed by an illustrated booklet, in verse, entitled The Children’s Friend: A New Year’s Present to the Little Ones from Five to Twelve written anonymously and published in New York in 1821. ‘SanctecIaus’ as he is here called is shown wearing a tall fur hat and possibly a fur suit, and sitting in a sled filled with baskets of ‘rewards’. The sled is being drawn by a single reindeer over the snow-covered roofs of New York. This publication was in turn followed by Clement Moore’s most memorable poem, Ά Visit from St. Nicholas’, written in 1822 but not published until 1837.

It was in Moore’s poem that the gift-giving saint acquired most of his remaining secular characteristics. These were a synthesis not only of living’s St. Nicholas and The Children’s Friend but of elements derived from Nordic mythology and especially the god Thor

— a bon vivant and patron of the poor

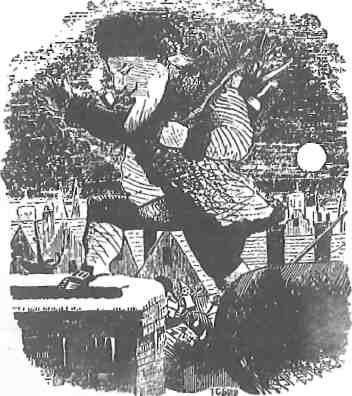

— and also known as Thonar, Donner, Donder, and Thunder. A log from Thor’s sacred oak used to be burned in his honour as the Yule God on New Year’s Day. Thor, according to folklore, had a crown of fire that encircled his head like a halo, and travelled through the heavens in a cart drawn by two goats named Tanngniostr (Tooth-cracker) and Tanngrisnr (Toothgnasher). His hair and his favourite colour were red. Moore, drawing on these various sources, enriched and further secularized the legend of St. Nicholas and his nocturnal visits. He substituted a team of reindeer for the single reindeer in the anonymous 1821 publication, and gave to some of its members Teutonic names. He supplied a wreath of smoke around St. Nicholas’s head for Thor’s ring of fire, emphasized his fur suit ‘from his head to his foot after Pelznichol (Furry Nicholas). He changed his visit from the eve of the sixth or the thirty-first of December to Christmas, which was becoming the favourite gift-giving holiday among Americans. In the same year as the publication of Moore’s poem, Robert Weir painted a ‘Saint Nicholas or Santa Claus’ preparing to leave a living room through the fireplace after having filled with gifts the children’s stockings hanging by the hearth. The cartoonist Thomas Nasi almost yearly in the 1860s illustrated this popular figure with a dark fur suit in Harper’s Weekly. The name Santa Claus, a confusion of Italian and Teutonic names and genders, became increasingly common from the middle of the nineteenth century. The Christmas tree remained very closely associated with him, in the belief that he brought it along with the gifts. Indeed, in one of his illustrations, Nast shows Santa Claus cutting a Christmas tree from a giant living fir—which is already decorated!

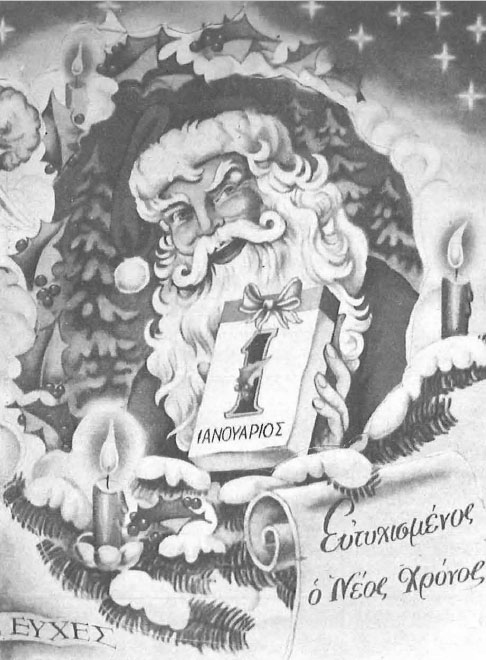

The reappearance of St. Nicholas in Greece during the post-war period — this time in the guise of Santa Claus — no doubt provided the proper stimulus for the radical transformation of St. Basil or the amalgamation of the two personalities. The fusion of the two saints and the manifestation of other Christmas associated traditions new to Greece — the yule tree and the spreading practise of exchanging presents on Christmas as well as on New Year’s — seem to have coincided with the arrival after the Second World War of large numbers of Americans and Greek Americans. Represented in the usual Byzantine manner appropriate to a saint up until then, within the past twenty years or so St. Basil has acquired practically all the characteristics and attributes of the American Santa Claus, whether in impersonations, pictorial representations, cartoons or greeting cards. In newspapers or magazines and now on television, he is referred to as Agios Vasilis with perhaps the explanation that he is called Santa Claus or St. Nicholas in most other Western societies.

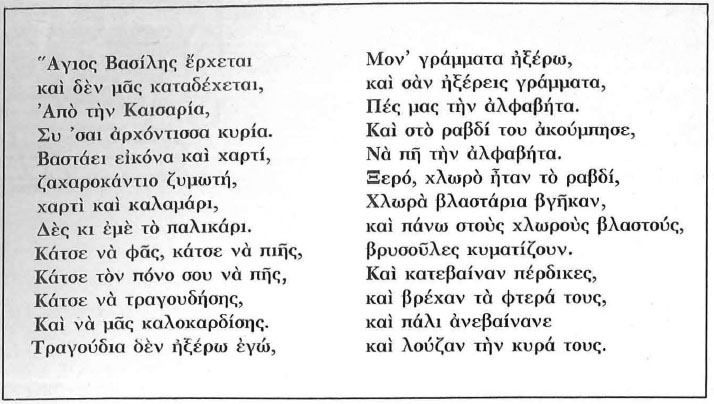

These developments may be disconcerting to traditionalists, but one must remember that the capacity and ingenuity of the popular imagination to ignore proprieties and to bridge gaps of time and space gave birth to customs that are now accepted. Consider St. Basil’s carol — the Kalanda sung in Greece at New Year’s. W.R. Haliday’s serious scholarly examinations of the Byzantine manuscripts which contain different versions of the carol (the results of which were published in 1924 Folklore Studies) have discouraged any reliable connection between the carols and St. Basil the Great. Nevertheless the popular myth-making faculty accepted the uncanonical but genial image of a saint who comes from distant Caesarea of Asia Minor to bring luck through the Vasilopita, education through the recitation of the alphabet and through writing (symbolized by his readiness with paper, pen and inkwell) and by his miraculous transformation of his pilgrim staff into a flowering tree alive with singing birds. This image represents the secular ‘alter ego’ of a saint — someone who could join a convivial group of peasants at a taverna — but bears no resemblance to St. Basil one of the Fathers of the Greek Church. Human characteristics no doubt created a bridge between St. Basil and Santa Claus — the ‘alter ego’ of St. Nicholas. And so it was that the two saints born in Asia Minor were ‘repatriated’ to the eastern Mediterranean and, here in Greece, amalgamated.

Today the ubiquitous presence of Santa Claus has been established internationally: from New York to Tokyo, from the South Pole to North Pole, where he now has his regular abode. As Agios Vasilis, Santa Claus, Pere Noel, Father Christmas, or Father X, regardless of ecclesiastical or scholarly frowns of disapproval, he will continue to bring holiday cheer on December 6, at Christmas or on New Year’s Day.