When I returned there last month to visit the site of Mycenae on the centennial of Heinrich Schliemann’s discovery of the famous shaft graves and their fabulous gold treasures, it was just twenty years since my own first visit.

I had left Athens early one afternoon in October, 1956, my head full of the bloody legends of the House of Atreus: of Agamemnon murdered by his wife, Clytemnestra, and her lover, Aegisthus; of Clytemnestra herself murdered in turn by her son, Orestes, with the assistance of his sister, Electra.

As the old bus hurtled through the gorge of Dervenaki, down from the hills of Nemea into the plain of the Argolid, my bench companion — and it was a bench, insecurely screwed into the corroded floor of the vehicle — began poking his finger alternately out of the left window and into my right side. Becoming aware that I could not understand him, he started to shout, and finally, exasperated with my stupidity, he threw himself onto the floor of the aisle, closed his eyes and began to snore. At first I thought he was having some sort of fit, but as several of the other passengers now began to shout and point as well, I realized he was trying to communicate something of importance. At last he roused himself and began to speak slowly, pointing out of the window. I suddenly realized that the spot towards which he was pointing — a brown knoll rising from behind two lower hills to the east — was the citadel of Mycenae, where Agamemnon had been buried three thousand years before.

A moment later the bus was careening into Phychtia, the village nearest to Mycenae which is served by bus from Athens. I was handed down my valise from the roof of the bus along with a wicker basket which I had never seen before, but I understood the accompanying gestures to mean that I was to deliver it ‘up there’ in the direction of the site. Suddenly alone in a cloud of exhaust smoke and chicken feathers, I wondered what might be ‘up there’.

As the cloud drifted away, I saw a long, narrow road lined with eucalyptus trees across the road from where I stood. It led across the valley and up to a small village on the side of the hill. Consulting my guide book I discovered that its name was Harvati and that it had an inn: La Belle Helene de Menelas — ‘eight beds, very simple but clean”.

I crossed some railroad tracks, passed the tiny Mycenae train station, and started up the narrow road. The shadows of the trees were lengthening when I noticed a tag attached to the basket on which I made out the first words ‘To Mr. Orestes…’ It suddenly and irrationally occured to me that, if I looked under the coarse black cloth covering the contents of the basket, I might find the severed head of Clytemnestra.

It was almost dark when I reached the village. Kerosene lamps were burning in the windows of La Belle Helene, where I was greeted by a tall man with a limp who announced that he was the innkeeper and that his name was Agamemnon. My astonishment was increased by the innkeeper’s face which, with its firm mouth and eyes set very closely together, strongly resembled the famous gold mask I had seen a few days earlier in the national Archaeological Museum and which Schliemann had pronounced to be the Mask of Agamemnon.

I felt that I had stumbled into the House of Atreus, but I soon learned that instead I had entered one of the most famous hostelries in Greece and that my reactions on arriving had been shared by many travellers before me. Today La Belle Helene still has only five rooms to let, and although the cost has risen to seventy-seven drachmas per bed, the inn’s official category is fifth class. This is irrelevant however, as among all the hostelries in the country, it is in a class by itself for its connections with the history of archaeology.

In the last century, there have been four particularly fruitful periods of excavation carried out at Mycenae by four generations of archaeologists. During this time the owners of La Belle Helene have not only served them as innkeepers but have worked on their most important excavations, frequently as foremen.

The first, or Schliemann period, was brilliant but brief, and ended in 1877. A second period began in 1886 when Christos Tsountas, promoted by the Schliemanns, started excavations that lasted until 1902. In 1920, a third period began when the director of the British School of Archaeology, Alan Wace, encouraged by both Mrs. Schliemann and Tsountas, acquired permission to continue their work. He, and the American archaeologist, Karl Blegen, together with an outstanding team, had particularly productive years in and around Mycenae in the early twenties and late thirties. A fourth period dates from 1952, when John Papadimitriou, director of the Archaeological Service and personal friend of Alan Wace, uncovered the Outer Grave Circle. George Mylonas, closely associated with Papadimitriou, has continued work down to the present. All of these men, famous in the world of archaeology, and many others only a little less well-known, have stayed for long periods at La Belle Helene, spending there many of the most triumphant days of their careers.

ALTHOUGH Heinrich and Sophia Schliemann had stopped two years earlier for a brief survey of Mycenae, it was in August 1876 that they came to stay. There were only six dwellings in Harvati at that time and the largest of these was the two-storey stone structure, the home of the Christopoulos family, built in 1864.

Christopoulos, one of the first workmen to be engaged by Schliemann, agreed to rent out most of the rooms to the Schliemanns, and the Christopoulos family moved into one of the three outbuildings behind. The two upstairs front rooms became the Schliemanns’ private apartment, and ever since, to occupy these rooms is a proof of prestige in the archaeological world.

The inn was given its name at this time by Heinrich Schliemann in honour of his wife. Three years earlier at Troy he had adorned her with a priceless hoard of jewels they had just unearthed together and conferred on her the sobriquet La Belle Helene, in the certainty that they had found the jewels which had once hung about the head and shoulders of Helen of Troy.

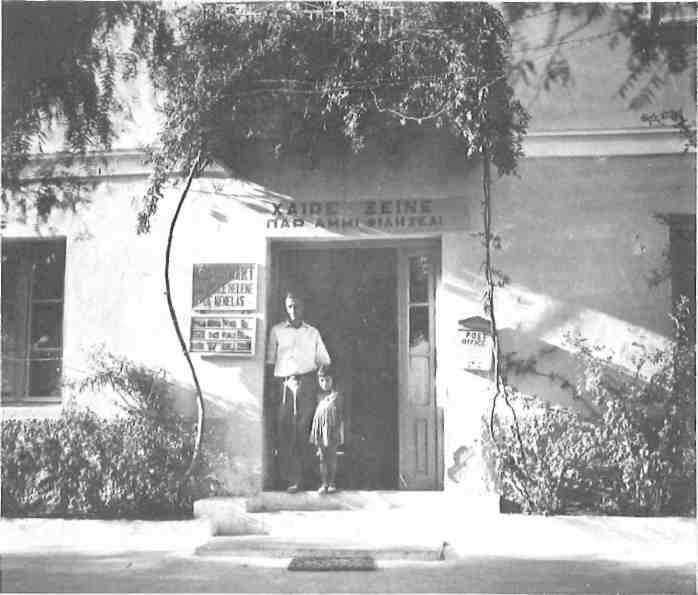

Schliemann also suggested the motto that is still spelt out over the front door:

ΧΑΙΡΕ ΞEINE ΠΑΡ ΑΜΜΙ ΦΙΛΙΣΕΑΙ

‘Hail, Stranger, welcome shalt thou be’

— these being the words with which Telemachus greets the disguised Pallas Athena on her arrival in Ithaca at the beginning of the Odyssey. The Schliemanns occupied La Belle Helene during the last five months of 1876 when they uncovered the riches of the shaft graves. The first celebrated tourist to the excavations was Dom Pedro II, Emperor of Brazil, whose visit Schliemann describes in his vivid account, Mycenae, published in 1878:

‘Coming from Corinth, His Majesty rode direct up to the Acropolis and remained there for two hours in my excavations… Afterwards [we went] to the Treasury of Atreus, where dinner was served. The meal, in the mysterious dome-like underground building nearly forty centuries old, seemed to please His Majesty exceedingly.’

That he stayed the night of October 30 at La Belle Helene is probable, although there is no record of it.

The greatest discoveries, however, were made in November, culminating in the excavation of a masked, semi-mummified body smothered in gold which Schliemann pronounced to be Agamemnon himself. Schliemann telegraphed George I, King of the Hellenes of his finds on November 28. By this time the news of the discovery had spread like wild-fire through the villages of the Argolid and hundreds of country folk had begun to gather at Harvati. Beacons burned at night on the neighbouring hills to protect the finds. The procession bearing this royal treasure down from the citadel passed by La Belle Helene on its way to Argos and eventually was brought to Athens. The Schliemanns left in December, returning only briefly in the spring of the following year.

The next important excavator and resident at La Belle Helene was Christos Tsountas, the first great Greek-born archaeologist to specialize in prehistory. In 1886, when he began clearing the palace on the Acropolis of Mycenae, he employed a number of girls as site workers, one of whom was Ioanna Christopoulos. Being the daughter of the proprietor of La Belle Helene, she was locally considered to be an heiress. Later archaeologists remember her as being grand in manner, although always followed by a gaggle of geese. Also among the workers whom Tsountas employed was a young man from Epirus, Dimitri Dassis, whose skill Tsountas particularly valued.

While excavating on the Acropolis, Dassis’s eyes fell on Ioanna, or, as one of his sons says today, they had already fallen on her father’s inn. Christopoulos opposed the match, but Dassis, encouraged by Tsountas, with the assistance of several young friends abducted Ioanna

— presumably with as little difficulty as Paris did Helen three millennia earlier

— and made her his wife. This was how La Belle Helene became, on the death of Christopoulos, the property of the Dassis family.

Dimitri Dassis continued to work with Tsountas not only at Mycenae but at other sites. He was his foreman in 1889 when Tsountas excavated the partially pilfered Vaphio tholos tomb near Sparta where he found the famous cups of the Tame and the Wild Bulls now in the National Archaeological Museum. Years later, during the celebration that followed the opening of the unplundered Dendra tomb some miles south of Mycenae, Dimitri was on hand to drink Nemean wine from the now equally famous Octopus Cup that had been just uncovered. Remembering that he had drunk wine from the Vaphio cups over a third of a century before, he exclaimed that he could now contentedly die.

DIMITRI and Ioanna Dassis had six children. One daughter died young but the second, Eleni, continuing the name of the inn, was a great beauty, and herself referred to by archaeologists as the Fair Helen. Today she lives in America. Of the four sons, Spyros was killed in Asia Minor in 1922, but Kostas, Agamemnon and Orestes live today within a few steps of La Belle Helene, which is now managed by Kostas’s son, Dimitri and Agamemnon’s son, Achilles Yorgios.

Kostas Dassis today is a vigorous man in his eighties and attributes his good health to his childhood diet of bread, olives and garlic. The only elementary school in the upper Argolid then was in Phychtia. Kostas and about twenty children walked there and back everyday from Harvati. The school had three hundred pupils who came from all the neighbouring villages, and one teacher. ‘No wonder,’ he says, ‘we did not learn our letters very well there.’ One of Kostas’s earliest memories from the turn of the century is being sent down, barefoot as usual, to the railway station with a pair of donkeys to fetch Mrs. Schliemann on the afternoon train from Athens. She was a widow by then — Schliemann had died in Naples in 1890 — and she returned occasionally to La Belle Helene, although she never visited the ruins after her husband’s death. Kostas also remembers the Crown Prince of Sweden, later King Gustav VI, an accomplished archaeologist who dug at Asine near modern Tolo. As a young man Kostas led the Crown Prince’s party up the Argolid from Asine to Harvati where he stayed a few days.

Kostas’s brother, Agamemnon, began his career as a foreman in 1920 when Alan Wace at Mycenae began the most systematic series of excavations to date in the annals of Greek prehistoric archaeology. Today Agamemnon lives just across the road from La Belle Helene where he and his wife, Vasso, run a small boardinghouse. When he speaks of the past, Agamemnon likes to get the mythological facts straight. ‘King Agamemnon’s brother, you will remember, was Menelaus and Queen Clytemnestra’s sister was Helen. So they were all part of the family here.’ Being younger than Kostas, his memory does not go so far back, but he remembers Harvati ‘when it had nothing, not even mosquitoes, because there was so little water.’ After the Second World War, when Agamemnon became president of the community, he saw that a water supply to serve the village was brought down from the Perseia Spring behind the citadel which had been the source of water for Mycenae during the Bronze Age.

In October, 1951, while working on the restoration of the Tomb of Clytemnestra just outside the walls of the citadel, Agamemnon discovered some carved stone, suggesting the existence of a nearby grave monument. This led to the discovery of the Second, or Outer, Grave Circle by John Papadimitriou, who together with George Mylonas, brought to light the most spectacular finds at Mycenae since Schliemann’s, and which are exhibited next to his in the great Hall of Mycenaean Antiquities in the National Archaeological Museum in Athens.

Agamemnon, however, remembers with deepest affection the great American archaeologist, Karl Blegen. Blegen, whose field work was carried through with a finer scientific exactitude than any of his predecessors, is best known for his work at Troy in the thirties and his excavation of the Palace of Nestor at Pylos begun in 1939. In the twenties, however, he excavated at Prosymna, three miles south of Mycenae. Blegen’s close association and lifelong friendship with Alan Wace is one of the most fruitful and inspiring chapters in Greek archaeology. They frequently worked together — at Troy and Pylos, as well as at Mycenae. Their chronology of mainland Greek pottery is a landmark in archaeological methodology which led to a famous controversy with Sir Arthur Evans, the great excavator of Knossos, as to whether Mycenae dominated Minoan Crete in the Late Bronze Age or Crete dominated the mainland.

An anecdote illustrates both the beginnings of the controversy and the prestige connected with La Belle Helene’s upstairs front rooms. In 1920, when Wace led the first British excavations at Mycenae, he and Blegen drove down from Athens in a jeep. Several miles before reaching their destination, they were stopped by a flagman to let a train go by. As the train slowly passed the crossing, they recognized in one of the carriage windows, the formidable presence of Sir Arthur Evans. Evans, whose major concern in visiting Mycenae was to try to find some evidence that would make Knossos more important, was delayed at the Mycenae station with his luggage. The younger archaeologists, with their jeep at full throttle, reached La Belle Helene first. They were escorted up to the front rooms, and Sir Arthur had to content himself with one in the back.

Kostas, Agamemnon and Orestes all worked under Wace at Mycenae and under Blegen at Prosymna, and although the brothers speak affectionately of Blegen’s kindness and generosity, it was Kostas who led a workers’ walkout for a fifty-lepta increase in their daily wage. ‘We used to earn about twenty drachmas a day then, and we won the strike right away. A few years ago when the newspapers arrived at the grocery in Harvati announcing Blegen’s death, all of us in the shop wept.’

After their father’s death, the Dassis brothers shared in the work as innkeepers at La Belle Helene. Agamemnon had the dubious honour of serving Goering and Goebbels in the thirties and Himmler right after Germany completed its occupation of Greece. He remembers Goering best who stopped at Mycenae for a meal during a propaganda tour of Greece. He began with a large plate of anchovies, olives and sardines. He then went through a roast chicken and some okra. He was so fond of the okra that he had three extra portions wrapped up which he took away with him.’

Agamemnon worked with British Intelligence during the war, eavesdropping on the German guests at La Belle Helene, and an official commendation from Field-Marshall Alexander, British commander in chief in the Middle East, is one of his most treasured possessions. While Agamemnon frequently served at La Belle Helene, Orestes was usually in the kitchen. A fine foreman himself who often worked with Wace, he was even more celebrated as a cook. Another great banquet which was held, like the Emperor of Brazil’s, in the Treasury of Atreus took place in 1939. On this occasion many luminaries in the world of archaeology gathered to wine and dine on the occasion of Alan Wace’s sixtieth birthday, and the feast was catered by Orestes.

WHERE have all those beautiful years gone?’ Kostas Dassis ask today. ‘Wace, Blegen, Papadimitriou, they are all gone. We are all just passers-by here at Mycenae.’

Today Harvati is not as it was twenty years ago, but it has not altered as greatly as it might. Kostas is aware that there are thirty car-owners for sixty houses and that the donkey population is greatly depleted. Nearly every house has a telephone, whereas two decades ago La Belle Helene had the only one — a wheezy old machine that rarely talked back. And everyone seems to have a refrigerator in a village which did not have electricity ten years ago.

Yet Harvati is still a place where few travellers spend the night. Most tourists are on a quick day – tour from Athens or stay in Nauplia where they can recover from the archaeological rigours in greater comfort. At sunset when the archaeological site closes and the last Pullman has roared back down the road, a kindly quiet settles over the villages which will not be disturbed till morning.

La Belle Helene has altered, too. The front of the lower storey was concealed a few years ago by the addition of a new reception room, and the interior of the sitting-dining room has been modernized, but some of the old photographs and paintings and the famous guest books are still there to be perused. The five bedrooms upstairs ‘for the stranger, welcome shalt thou be’ are intact, too. Although the Dassis family-house behind the inn has been demolished to build a new kitchen, the other two outbuildings remain, one of which served as Schliemann’s study and the other as his storage area. From the terrace the gentle view into the Argolid can be seen over what Lawrence Durrell (quoted by Henry Miller) called ‘heraldic fields of green’, and the pepper trees still stand beside the hotel under one of which Miller’s colossus, George Katsimbalis, napped after a hearty lunch surrounded by learned German tourists on the eve of World War II.

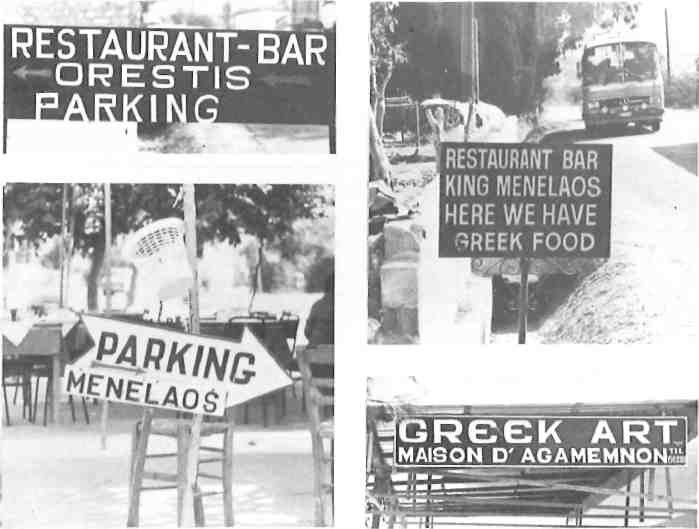

Today the main street is lined with signs: Orestes Parking’, ‘Iphigenia Youth Hostel’, ‘Homer Bar’, ‘Electra Rooms’ and ‘Greek Art: Maison cf Agamemnon’. Before one dismisses such things, however, as modern vulgarities cashing in on the past, it is well to remember that there are a number of Agamemnons, Oresteses, Iphigenias, Electras, and at least one Clytemnestra, walking about Harvati today, and the signs may just as well refer to their proprietors as they do to the personae of Homer.

The story of ancient Mycenae has a vividness that Olympia and Delphi lack for being a chronicle of a family whose members are all well-known. And, modest as it may be, modern Mycenae has its chronicle of a family as well.

The eucalyptus trees, although in great need of pruning, still line the road leading up to Mycenae and the little railroad station at which Mrs. Schliemann and, later, Sir Arthur Evans, descended is still there, even though the trains don’t stop there any more.

And one discrepancy remains, too: the Treasury of Atreus has been quite closely dated as belonging to a period long before the Trojan War, but despite the evidence of sherds the inhabitants of Harvati have insisted, still insist, and will most likely go on insisting, that it is the Tomb of Agamemnon, and that he alone will live on — even though he sleeps.