From the time he founded the American Farm School for boys in Thessaloniki in 1904, it had been his dream to include a girls school as well. Although he had been about to buy land for such a school before his death in 1936 at the age of ninety-one, he never saw his hopes materialize. His wife, however, who lived to be ninety-six, saw his life-long wish come true in 1945.

Today, with fifty boarding students, eight faculty members, and ten academic and craft courses, the Girls School has won respect and recognition as an important educational and progressive influence in the villages of Northern Greece. Although the program of both schools is continually changing to meet the needs of rapidly developing communities, the basic purpose remains the same: to educate minds, train hands, and build character.

It was on these precepts that the Girls School was begun under the direction of Joice and Sydney Loch. The Lochs had been in Greece since 1922, working with Quaker Relief for refugees from Asia Minor, and using the Farm School as their headquarters. In 1928 they moved to Ouranoupolis, a refugee village on the border of Mount Athos, where Mrs. Loch taught the women to make rugs based on Byzantine designs brought back by her husband from the Holy Mountain.

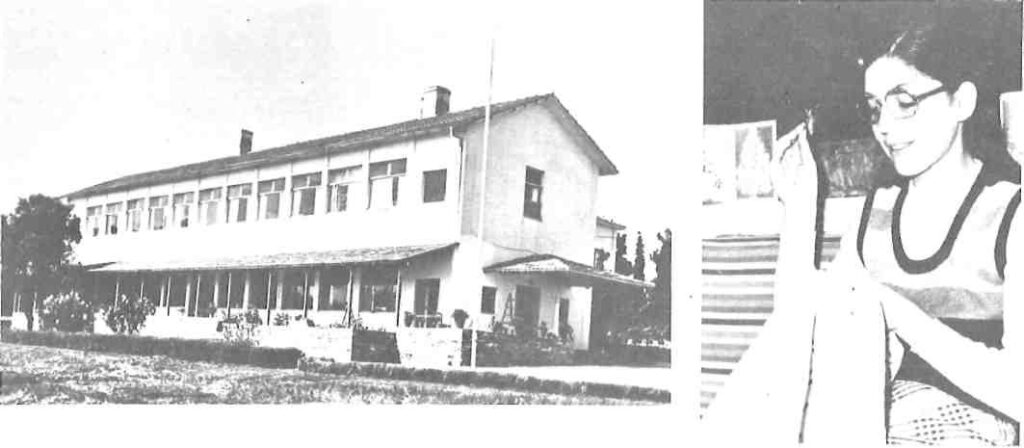

Over the years the lives of the Lochs continued to be intertwined with the life of the Farm School. When the school was reopened after the war, Sydney Loch was appointed temporary director in the absence of Charles House, the founder’s son. Seeing the devastation of the surrounding villages which were being terrorized during the Civil War of 1945-9, the Lochs opened the wooden barracks that had housed Farm School staff during the Occupation, and they used them as a sanctuary for sixty village girls from Macedonia. With the help of the Houses and the Farm School, the Lochs fed and clothed the girls, and eventually the Friends Service Council in London provided money, supplies, and later, teachers. In 1959 the British Quakers constructed a permanent building to replace the leaky, mouse-infested barracks.

During and after the fierce Civil War the chief need was to create an atmosphere of caring, reconciliation, and peace for the students. Due to the primitive conditions of that era, the main features of the girls’ curriculum were the growing, cooking and preserving of food, and childcare and hygiene, as well as elementary academic subjects. The school thus introduced an aura of calm into the students1 lives and a new climate of hope into the troubled countryside.

After supporting the Girls School for twenty years, the Quakers decided in 1965 to turn over their program to the American Farm School. Today the Girls School is just a ten-minute walk from the Boys School, six miles from Thessaloniki at the foot of the Panorama hills and Mount Hortiati, overlooking the Thermaic Gulf.

Through the efforts of committees working for the Girls School in Greece and in the United States, funds were provided in 1969 to extend and modernize the buildings. The kitchen was expanded to include room for demonstration cooking classes, and a modern gas stove replaced the old wood-burner. The open shed was glassed in to make a large weaving workshop, and the dining room was converted into a sewing room. Space has always been at a premium as the school continues to grow and so the new dining room was built to be a multi-purpose room. It serves as a sitting-room and classroom, a place for morning chapel, a library, and an exhibition room for rugs.

There are still aspects of the Girls School that are far from modern. The girls sleep in double bunks in three unheated dormitories. The dyeing shed is located in the former pigsty, with an old bathtub functioning as a dye pot, and the girls stir the skeins of wool in kettles over an open fire. Only half a basketball court has been constructed so far, and classes still begin and end by the clanging of the goat bell used since Quaker days.

There is a staff of twelve, including a cook, a handyman and a night guard. Mrs. William Hamilton, the director of the school, came to Thessaloniki originally in 1964 as the wife of the American Consul General. She was appointed to the position four years ago, following her husband’s death. As a member of the Farm School’s executive staff, she is a liaison between teachers and administration.

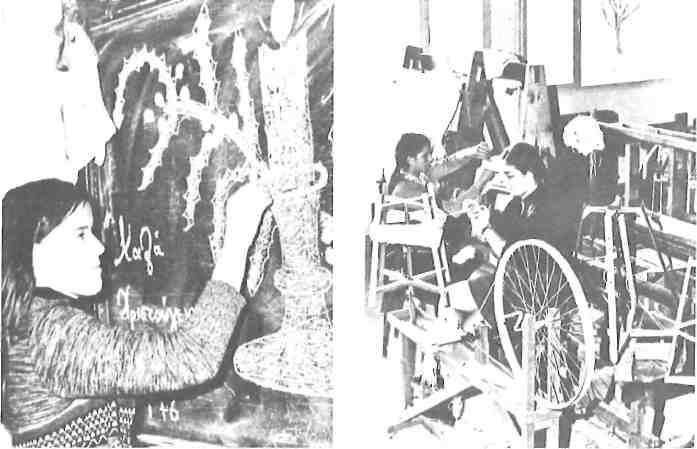

The school has long practiced the belief that a Greek can more effectively teach another Greek than a foreigner can. The only non-Greek teachers are those who have certain specialized skills: Phil Smith is a weaver-designer from the Rochester Institute of Technology; and Else Regensteiner, a world-famous American weaver, visits the school for six weeks each year and counsels teachers and students in methods and design.

Because all students are from rural backgrounds, they do not have the ability to pay the full tuition fees. The school produces more than fifty percent of its budget, but the rest, $460,000 per year, must be raised elsewhere in Greece, Europe, and the United States. Of the $1,700 per year that it costs the school to educate a girl, the girl’s family generally contributes $135. It is often difficult, however, for some families to raise even this amount.

At any time of day one is likely to find the girls involved in a variety of activities. Their day begins at six o’clock with the ringing of the hand bell. Two girls have already been up since five-thirty making breakfast. The students are completely responsible for the care and upkeep of their school; after breakfast each girl has a housekeeping duty — washing windows, mopping floors, sweeping, cleaning lavatories, making beds, watering flowers, washing dishes, or preparing food. At eight o’clock, classes start. The girls divide their time between theoretical and practical subjects. They study Greek, mathematics, history, religion, art, and English, as well as sewing, embroidery, weaving, machine-knitting and rug-making. Classes finish at four o’clock in the afternoon and, except for the girls who work in the kitchen, all have an hour’s free time before dinner. Study hall follows from seven-thirty to nine, with lights-out at ten o’clock.

In addition to the demanding daily routine there are lessons in Greek dancing and music, as well as physical education which includes volleyball, basketball, soccer, and modern dance. Once a week, speakers from outside the school come for discussions ranging from hair care to Greek folklore — any topic that might serve to open up new areas of thought for the girls. Besides bringing in various leaders of the community, the Girls School staff takes students on field trips to museums, theatres, churches, and nearby places such as The School for the Blind in Thessaloniki. After a recent visit there, the girls reciprocated by inviting the blind children to visit their own school.

On Saturday evenings there are skits, dances and films at the Boys School, and on Sunday all gather for the liturgy at the Farm School church. The volta — something the girls look forward to all week — follows church, before dinner in the boys’ dining room. in keeping with the villagers’ parental protectiveness the girls have no contact with the boys except for these weekend activities. Even then they are strictly supervised. Girls are not allowed to go unescorted into the city or to use the telephone freely either to make or receive calls. In many cases, Girls School Monitor C. Angeladaki comments, Ά girl wouldn’t be allowed to live away from home were her parents not sure that she would be this closely guarded.’

Adapting the curriculum and teaching methods to ever-changing needs is the job of Mrs. Vouli Proussali, academic dean. A graduate of the University of Thessaloniki in philology, Mrs. Proussali’s first stay at the school was from 1948 to 1952. She returned in 1967 and has remained ever since. ‘In classes, we encourage the girls to read, to judge critically and to articulate,’ she explains. lNo matter what future they have — as wage-earners or homemakers or both — they’ll enrich their own lives by developing such skills now.’ History classes become involved in civics and current events, while practical hygiene courses emphasize first aid and preventive medicine, all useful for rural life.

‘Usually a village girl has had little access to books, and here, often for the first time in her life, she has a library available to her,’ Mrs. Proussali says. The library, which has been sponsored by Sigma Kappa Sorority in the United States, includes reference volumes as well as books by Greek writers such as Kazantzakis, Penelope Delta and Myrivilis, and translations of Mark Twain and Dickens.

In their free time, the girls wash their own clothes, or work on projects such as embroidered placemats and napkins, macrame glasses cases, book markers, and baskets. These, together with handwoven rugs, stoles, pillows, and materials adapted from traditional Greek designs, are sold in the school boutique. Some of the proceeds go toward an annual school trip. It is hoped that the school will become a centre for the preservation and promotion of traditional crafts of Northern Greece. Also, it is hoped that the boutique will eventually serve as a market outlet for those who can produce the high-quality work for which it has already become famous. To this end some graduates have been hired as apprentices, living at the school and earning a salary.

Upon graduation, most girls return to their home villages with new ideas and skills. They are able to supplement their families’ incomes as well as lead satisfying and productive lives. One graduate who worked in an urban shoe factory for six months said recently: Ί prefer life in my village. In the city, I could drop dead and no one would care.’

Each girl who returns to her home can be compared to the priest who during the Easter service passes the light of his candle to another. Then the light is passed from neighbour to neighbour, and soon the village is illuminated. In a similar way, the girls of the American Farm School, by sharing and by example, are bringing new light and hope to their villages.