Thessaloniki has, over the centuries, witnessed more than her share of tragedy and weeping. Romans, Venetians, Serbs, Normans, Saracens, Turks, Germans, Italians and Bulgarians have marched through, pillaged and erased large segments of the population of ‘Salonica’, ‘Salun’, ‘Salonique’ — its name depending on the language of the conqueror. (First named Thessaloniki by Cassandar in 315 B.C. after his wife, Alexander the Great’s sister, in modern times, it has been the city’s official name since 1937). It was to hide the blood, not the red bricks, after a massacre in 1826 that the Turks ordered the ‘red’ tower whitewashed, and then rechristened it with the name by which the famous landmark is now known — ‘the White Tower’. It was here in Thessaloniki that the Young Turks began their revolt in 1908. The magnificent villa Allatini, where the banished Sultan, Abdul Hamid II lived from 1909-1912, still stands, one of the few remaining examples of the fascinating architecture of pre-concrete Thessaloniki. In 1912 King Constantine I marched victoriously into the city in the wake of the retreating Turks, thus averting a Bulgarian invasion from the North. In 1917 most of the city went up in flames in the so-called Great Fire (part of the city having burned down in earlier fires in 1890, 1898, 1910). By 1922, it was receiving a stream of poverty-stricken refugees from every corner of Asia Minor, and its population doubled overnight. The next two decades witnessed revolutions, coups, and countercoups, as the country sought to understand what kind of government the people wanted, but her darkest days were yet to come. The capricious hostility of the North was never far away. Despite Greece’s heroic Albanian defence against the Italians in 1941, the Axis powers eventually overran the city, rounded up the entire Jewish population — about sixty thousand people — whose ancestors had come here in the fifteenth century, and loaded them into box cars which carried them off to concentration camps. Fewer than two thousand returned after the war.

Liberation brought no peace. The conflicting ideologies which grew out of the underground movements of World War II led to the Civil War, one of the darkest moments in the city’s history. There was a brief period of peace in the fifties but even this was short-lived. The tragic and fatal attack on the left-wing Member of Parliament, Grigoris Lambrakis, in 1963 created new bitterness and re-awakened old antagonisms. Finally in 1968 Thessaloniki was the location of the first political trial of intellectuals opposed to the Junta dictatorship.

YET Thessaloniki is a city of resilience which leads people to speak of her as alive and dynamic; as the ‘pride of my heart’ and ‘mother of the poor’. It is this dynamism beset by ill-fate which has always given vigour to a city rejuvenated through the centuries.

She smiles — in the love of her citizens which is often nostalgic. The eyes of Machi Seferdjis, a member of an old, established family, light up as she speaks of the city’s history. ‘In 1821 there were 100,000 Turks, 100,000 Jews and only 8,000 Greeks living in Thessaloniki. The area from St. Dimitrios Church down along Aristotle Square to the waterfront was the Centre and market place for the town and the houses of people of consequence were built around the Square. The leaders of society lived out there,’ says Machi, smiling. ‘And everyone knew them. The richest people were the Jewish families for commerce was in their hands. The rich Greeks lived off their inherited property and did not have to work. In those days the big houses were by the sea and we could swim in the Bay, before it became polluted. I went to a girls’ school, or parthenagogion. Our parents were very Victorian. We were rigidly chaperoned and most of our marriages were arranged.’

Machi’s social life changed drastically with World War II. ‘There was a very strict curfew and I remember that from April, 1940 until October, 1944 my mother never went out in the afternoon. When the Germans allowed the Bulgarians to pass through Thessaloniki to settle in Edessa, my mother said she would rather take poison than see Bulgarians settle here.’

A smile which reflects still another pulse of Thessaloniki is that of Dimitri Zannas, lawyer, farmer, and civic leader. Dimitri’s memories of growing up in this city are a potpourri of peaceful times interspersed with wars, revolutions, and coups. Since the time of Dimitri’s grandfather, less than a hundred years ago, the population of the city has grown to seven hundred thousand. Dimitri works diligently on the City Council to help preserve the city as it grows, and he cannot hide his nostalgia for the smaller Thessaloniki of his youth. ‘We are on the threshold of moving from a city where individuals are important to a metropolis dominated by the masses. Fast growing cities crush the individual. Its rate of growth has been impressive. It is due of course to industrialization, which overtook agriculture as the main employer in the middle of the fifties.’ By the year 2000, he predicts, Thessaloniki will have doubled its present population.

Thessaloniki begins to seem over-crowded even today. The crashing din of the city’s main street, Via Egnatia, once the old Egnatian Way built by the Romans to connect Rome with Constantinople, is the pulse of the city, holding as it does a strategic position on the artery of the East-West communication and commerce. At the eastern end you hear the insistent voices of the forty-thousand students at the Aristotelian University. One of the best equipped in the Balkans, it is a magnet for increasing numbers of students from all over the world.

Directly opposite are the grounds of the International Trade Fair which come to life every September. Since its establishment half a century ago, fifty countries from five continents have participated at various times in promoting cultural and commercial exchanges. In its early years the Fair’s exhibitions focused on agriculture and handicrafts, but today manufactured products of all types from both small and large industry are displayed for the thousands of visitors. Many are attracted to the less commercial cultural events, folk dancing, and music and film festivals. Recently the Dimitria, the October Festival honoring the city’s patron, Saint Dimitrios, was revived. It originated in the twelfth century. Performances by chamber music ensembles, Byzantine choirs, operas, ballets, and ancient dramas, captivate the community every October.

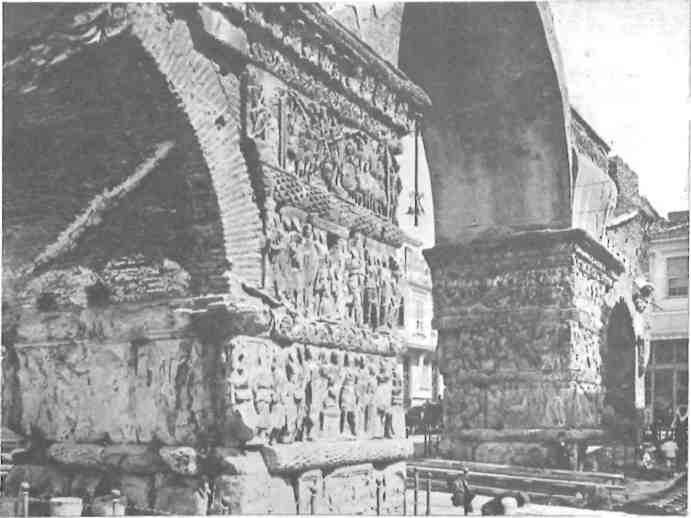

A short block farther down on Via Egnatia stand the remains of the Arch of Galerius and the Rotunda of Saint George. It was here in A.D. 305, that the Emperor Galerius built his triumphal arch depicting his victory over the Persians. It is covered with life-like scenes from battles, which bring to life the rumble of horses and chariots, camels and elephants, spears and shields, echoing the ancient glories of the Empire. The Rotunda, intended by Galerius as his mausoleum, was transformed instead into the palace church by Constantine the Great and was later dedicated to Saint George. When the city fell to the Ottomans in 1430, the building was converted into a mosque with an adjacent minaret. After the city’s liberation from the Turks in 1912 it was made into a national monument. In the Byzantine Empire, Thessaloniki became a Christian stronghold second only to Constantinople. Saint Paul addressed two of his epistles to the Thessalonians while he was here. In 850 Cyril and Methodius, who had learned the Slavic language in their neighbourhoods, left the city to Christianize the Slavs and translate the liturgy and the Bible.

The cobblestones on Via Egnatia have now been replaced by macadam, and the clang of the trolleys by the shrill whistle of traffic policemen with their frenzied waving to speed up the congested traffic. The blare of radios and television sets mingle with the hammerings of coppersmiths and furniture makers. Bread and gasoline, clothes and icons, fruit and drugs, X-rated movies and Turkish baths, musical instruments, sunken churches and sweet shops all have their place on the densely populated Via Egnatia. Walking down this street one can hear a veritable Babel of languages, as tourists. shoppers, and traders carry out their business.

At the far western end of the Via Egnatia is the Railroad Station where the sounds of diesels mingle with the cries of greetings and farewells. Nearby are the paliatzidika, or used-clothing stalls, where leather jackets, old boots, and overalls hang out to attract the customer. The tap, tap, tapping of bell mongers and harnessmakers come from dark, one-room shanties, an anachronism juxtaposed with the whirr of high-speed drills and the thumping of giant presses in the huge new industrial zone. In this industrial’ complex are representatives from all corners of the globe, whose companies include everything from oil refineries, rubber plants, steel mills, to plastic, tractor, cotton, and textile manufacturers. Yet the simplicity of earlier days is not totally lost along the Via Egnatia. Almost any morning at 2 a.m. finds groups of revellers, the glentzedes, on their way to the patsadzidika, those restaurants specializing in tripe soup to settle the digestion. The partygoers may move into the twentieth century by day, but by night there’s still time to sing to the ‘most beautiful girls in the world’.

On one of those rare mornings clear and free from smog, usually after a cleansing North wind has swept down the Axios valley, one can almost reach out from Thessaloniki and touch the snow-capped peaks of Mt. Olympus eighty kilometres away. On special evenings, when one looks down on the city, with its twinkling lights clustered in a semi-circle below the dark mountains, with the darker sea in front, what one sees is a sparkling jewel.

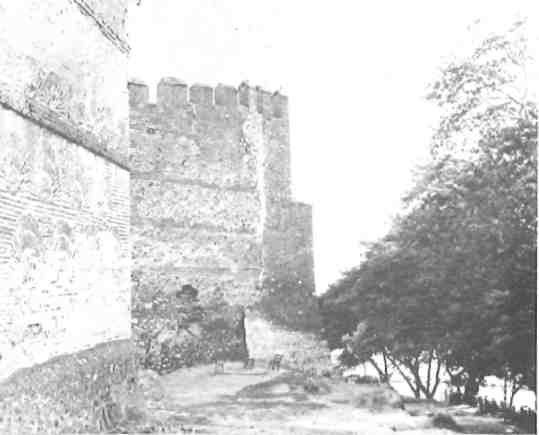

One can climb on the remains of the twenty-foot-thick crenellated walls which used to encompass the city, and look down from the Castle of the Seven Towers on a panorama of the city, old and new. There js still an inner rim of low red-tiled houses separated from the white high-rise apartments at the point where the devastating 1917 fire was stopped. Walking within the old town, a cobblestone street may narrow, twist, and suddenly turn into steps. Until recently, squatters lived within the walls, cooking on tiny charcoal braziers outside makeshift doorways. The smells of garlic and tomato sauce lingered in the air. On very narrow streets, the overhanging balconies of Turkish-style houses, where the women sat to watch the outdoor activities, still reach out and almost touch each other.

In the inner core of the city where the food markets are located, sights, smells and sounds assault the senses. Inside the Modiano Market, open stalls in consecutive alley ways display their produce. Fishmongers loudly compete in extolling their catch, butchers display hanging carcasses. Not so long ago chicken-sellers could be seen blowing air through straws into dead birds to make them look plump and more appealing. The vegetable vendors, usually outside, polish and arrange each item and keep a careful watch, ready to snare the passerby.

Stalls are lined in rows, flowers next to flowers, fish next to fish, meat next to meat, vendors selling the same products plying their trade next to each other, even up into the copper market where the sellers vie with their neighbours for the same customer. In Turkish times, copper utensils were tinned over, but today they are semi-buffed to give a patina of age. To test the authenticity of the metals, the visitor is urged to touch all the wares — pitchers, plates, trays, candle holders, bowls, braziers, and bells of all shapes and sizes in copper, brass, or bronze. In the fur market there is no greater pleasure than to run one’s hands over the smooth and ingeniously designed furs. All kinds and qualities of furs are to be found, from the indigenous stone martens and minks, to tiny remnants which are imported and pieced painstakingly and expertly together.

The exhausted shopper can find sustenance in the souvlaki shops which smell enticingly of charcoal-roasted shish kebab and donner kebabs of thinly sliced meats that twirl on vertical spits. In the back streets small tables that cannot fit inside the miniscule shops dot the sidewalk. The ouzeri provides a special variety of mezes. Any meraklis will tell you that ouzo requires more piquant meze than does wine: tzoutsikes, for instance, burning hot peppers that bring tears to the eyes or tsiros, pungent rope-like dried fish soaked in oil and vinegar, or avgotaraho, dried, pressed, fish roe encased in a wax covering. Specialities of the city include such delicacies as fried mussels with garlic dip, grilled and marinated red peppers and a variety of game and wild boar.

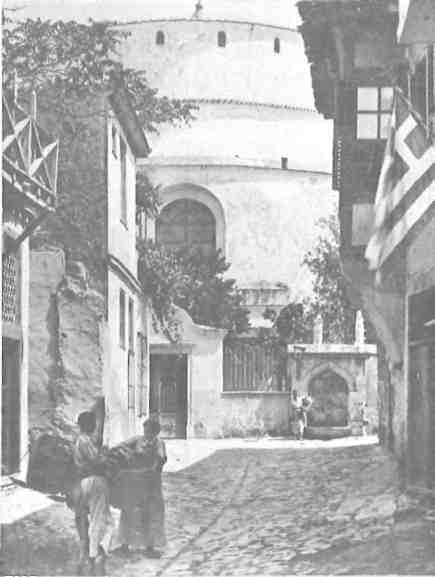

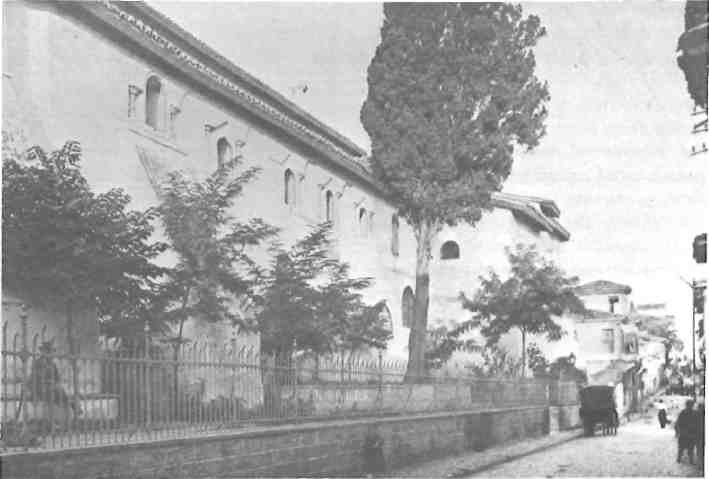

THE ethereal senses are. satisfied most in Thessaloniki by the many famous Byzantine churches and their remarkable frescoes. In St. George’s, a climb up into the six-metre-thick circular walls affords a closer view of the ceiling’s mosaics, magnificent portraits of the saints praying in front of third-century Roman buildings. In the tiny chapel of Hosios David there is an extraordinary mosaic portraying the vision of the prophet Ezekiel, which shows Christ in a sort of translucent bubble and dates back to the fifth century. Of the three hundred sixty-five churches that were built in the city during the Byzantine millennium, there are twenty left. Each has something unique, some gem reflecting the art of its particular period. The decorative mosaics of Panagia Ahiropiitos (Our Lady Not Made By Hand) are typical of the sixth century, while the superb Ascension in the dome of Aghia Sophia is representative of the seventh century. Both the later brickwork and the thirteenth-century frescoes of St. Catherine’s and The Church of the Twelve Apostles are examples of exceptionally fine work, although the frescoes are not very well preserved. The basilica-style church of St. Dimitrios is of particular interest. The young Roman soldier who became a Christian was martyred in A.D. 303. A small church was built over his tomb; destroyed by fire, it was rebuilt in the fifth and seventh centuries. It was almost completely destroyed by fire again in 1917 but there are remains of the original which have been restored. The mosaics that have been preserved show the protector saint of the city, the young and beautiful St. Dimitrios, with his arms forever embracing those about him.

Like any woman worth becoming attached to, Thessaloniki is a lady of changing moods, modes and styles and must be sensed to be understood. The casual visitor may see the beauty or even search deep enough to find many of the blemishes. But only time and intimacy can change superficial friendship into an abiding love. Thirty years of living here has taught us that love for Thessaloniki can grow out of many and varied experiences: spending an evening with your parea, your own circle of friends; standing in reverence among Thessaloniki’s throngs on the Via Egnatia in 1951 as an army tank carrier bore the dead, octogenarian Bishop Genadious sitting on his throne, complete with his gold crown, on his way to be buried upright in the city’s cemetery — a privilege reserved only for Patriarchs and the Bishop of Thessaloniki; joining a leftist friend at an anti-British demonstration in Platia Eleftherias (Freedom Square) in 1954 while listening to his assurance that the Americans’ turn would never come; sitting on a cliff overlooking the Thermaic Gulf listening to Katina Paxinou, Alexis Minotis, Leonard Bernstein or Manos Hadzidakis as the moon moves across the sky in the early hours of the morning; living through times when you know you are distrusted because of your passport; weeping with a friend while reading Mangakis’s iLetter in a Bottle’, written from solitary confinement; trying to talk with friends at a taverna over the din of the bouzouki and the singing, and sensing that personal friendships transcend politics.

And there is the city itself: watching the sun set in a splendour of pinks and oranges behind Mt. Olympus; walking through the sokakia, what’s left of the narrow streets of the old town, at a pace which gives you time to savour the sounds of the neighbourhood; strolling along the quay toward the White Tower after a storm, remembering the old days when the waterfront was lined with caiques, the coastal sailing boats that plied the Aegean Islands; feeling the tension grow in the city as workers, university students or the populace as a whole decide to take to the streets in protests; walking through the poverty-stricken areas where flattened oil tins still serve as windows or shutters, but where even in their poverty the people find time to plant flowers, share a ‘good morning’, and a smile.

Few people would call Thessaloniki a religious city and yet her churches are filled to overflowing on saints’ days. Just as the villages of Greece open up their hearts on the one or two special festival days, so one finds a special sense of festivity and open-heartedness in Thessaloniki during the period of the Dimitria, beginning with the opening of the Fair in September and ending with St. Dimitrios weekend on October 26th. Two months of Fair – going, festivities, concerts, and theatres, fill the air with celebration.

On the night following the Fair Inauguration, the people of the city, swelled by visitors from the countryside, pack the streets to overflowing as they do on St. Dimitrios Day. They eventually wind their way to the sea to watch an exhibit of fishing boats, naval vessels and fireworks lighting the waterfront. There is a warmth in those throngs which invites the outsider to share in the life of their city. To the outsider Thessaloniki comes to life when she celebrates. For those who have remained to learn her many languages, her life seems to be as timeless and as full as the centuries that the story of Thessaloniki has spanned.