We are not referring to the trials and tribulations that beset the construction of even the simplest building in Greece; although gargantuan, such problems shrink in comparison to the aesthetic, social, and political issues that are born the moment plans for public buildings are conceived. The mere whisper of a suggestion to erect such edifices instantaneously spawns a plethora of pros and cons, which immediately give rise to more pros and cons, which soon blossom into heated controversies guaranteed to preoccupy the nation for decades.

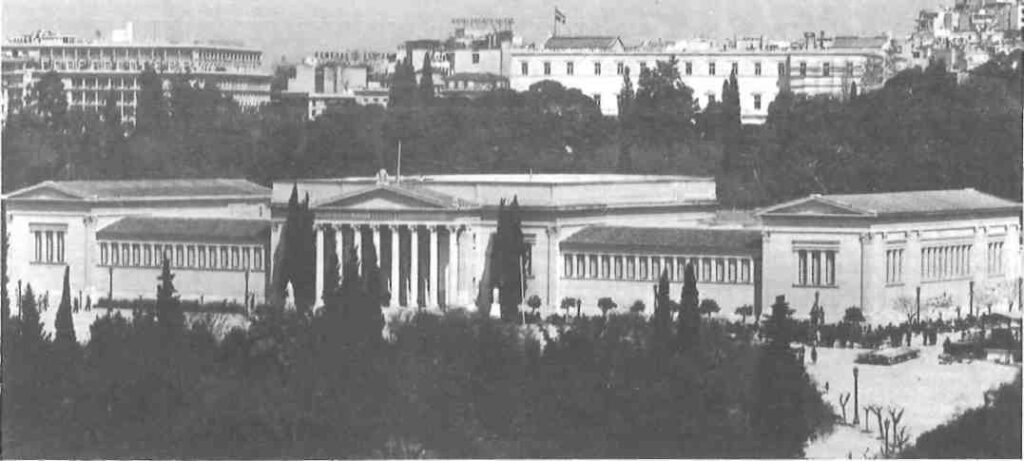

Consider the Zappion Exhibition Hall, one of the city’s most famous landmarks. Proud and aloof, it stands magnificent but silent in its own Zappion Gardens which sit cheek by jowl with the former ‘Royal Gardens’ (now the ‘National Gardens’), at one time part of the buffer zone between the Parliament buildings at one end and the Royal Palace at the other.

Today, Prime Minister Karamanlis cuts across the gardens as he makes his way from his apartment near the Palace to his offices. Perhaps he makes an occasional detour and passes by the Zappion, contemplating, no doubt, its illustrious history, and the zealous patriots after whom it is named: the cousins, Evangelis and Konstantinos Zappas.

Evangelis Zappas was the older of the two. Born in 1800 in Ipiros, he won fame and glory during the War of Independence as a protopallikaro — a brave, first lieutenant — of Markos Botsaris, He later fought beside another great leader of the Revolution, George Karaiskakis, whose acts of heroism are indelibly planted in the Greek mind, nostalgically and affectionately recalled by old-timers and school children alike. During one battle, according to legend, the intrepid Karaiskakis turned his back to the enemy, raised his fustanella, delivered a thunderous message of defiance, and promptly received a well-aimed Turkish bullet for his pains. It is not known whether Evangelis Zappas was present at this incident.

Be that as it may, with the struggle for Greek freedom at an end, and independence a fait accompli, the thirty-one-year – old Evangelis did not relish long periods of inactivity in a peacetime army, especially after eighteen years of action. Resigning from military service, he set off in 1831 for Rumania with the express purpose of making a fortune which he then could donate to the fledgling Greek nation. In the ultimate patriotic gesture, he took a vow to remain unmarried and to dedicate all the fruits of his labour to his homeland, a vow which was later shared by his cousin, Konstantinos.

During his years at the battlefront, Evangelis had acquired considerable practical surgical training. Upon reaching Bucharest, he immediately set himself up in medical practice. Many of the members of the establishment of Rumania at that time were Greek, and eager to have a hero of the Greek War of Independence administer to their complaints. Little is known about the fate of his patients, but the fact that Evangelis soon built up a flourishing practice suggests that his hard-knock school of medicine could not have been particularly lethal.

Attending to the health of his wealthy patients did not prevent him from exploring other areas of productive enterprise, however. While fighting in the various campaigns of the War of Independence he had made the acquaintance of a French philhellene who, when not fighting for the Greek cause, was in private life a renowned agriculturalist. With his usual insatiable curiosity, Zappas had gleaned considerable information about the science of agriculture from his friend. His trained eye immediately noted the primitive methods of cultivation being practiced in Rumania. Renting property attached to a Greek Orthodox monastery, he set about applying his knowledge. In a few years, the yield from the land had multiplied tenfold. Word of his success reached the ears of Rumanian landowners who began clamouring for his services. Sending to Greece for his cousin Konstantinos to help him, he expanded his activities, leasing Rumanian estates and providing the landowners with greater profit than they would normally realize and earning huge profits for himself. In a few years both he and his cousin were multimillionaires.

A large part of this fortune would eventually be spent on the Zappion, whose story begins in 1858 when the ever receptive Evangelis Zappas read an article written by Panayiotis Soutzos in which the romantic poet described the ancient Olympic Games with great lyrical verve and license. Soutzos advocated the Games’ revival, thus anticipating by several decades the founder of the modern Olympic Games, Pierre de Coubertin. Soutzos’s article fired the imagination of Evangelis who promptly put plume to paper and dispatched a letter to Greece’s new king, the young Bavarian, Otto, placing at the monarch’s disposal the bulk of his fortune to be used to reinstate the Games. Simultaneously, as a gesture of his good faith, he had delivered to the King the sum of one million drachmas, an enormous amount at that time.

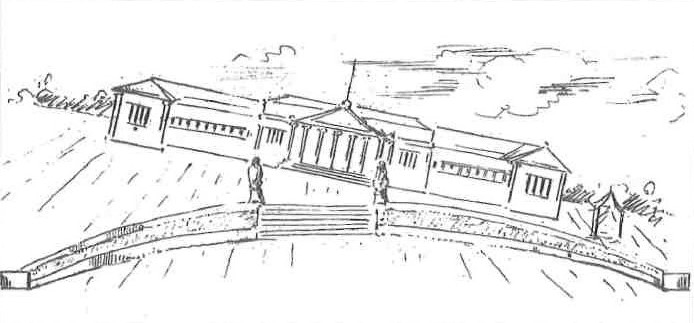

Upon receipt of these communications, King Otto went into consultation with his Minister of Foreign Affairs, the able Alexandras Rangavis. Neither gentleman, regrettably, was graced with much foresight, and the notion of modern Olympic Games struck them as simply nonsensical. They agreed that Evangelis’s dream, while well-intentioned, ‘came from the heart rather than the mind’. Evangelis’s fortune, however, was an entirely different matter and well within the confines of their vision. Anxious not to cool the zeal of such an ardent patriot, and above all not to lose the one million drachmas, they sent a tactful letter to Evangelis suggesting alternative uses for his contribution. The country was in need of an exhibition hall, they informed him, one where agricultural, industrial, and cultural exhibitions could be organized for the Nation’s enlightenment. In a conciliatory gesture, they suggested that athletic matches could be organized on Sundays, during the period of the exhibition. The building, Evangelis was informed, would cost one million two hundred thousand drachmas. Evangelis agreed to this arrangement and the celebrated French architect, Boulanger, then residing in Athens, was called upon to design the edifice. The Government, not to be outdone in generosity, decided to donate the site. They carefully chose a barley field situated near the ancient Panathinaiko Stadium, in keeping with the spirit of Zappas’s dream. This stadium was eventually restored for the first modern Olympic Games in 1896.

Before the King and his Government could acquire the site, however, they had to contend with the peasant who owned it. A stubborn gentleman, he refused to relinquish his property for less than nine thousand drachmas. The King and his Government — ever mindful of the taxpayers’ money — stood firm, refusing to pay more than two thousand drachmas for the land. Both sides, in fact, gritted their teeth and stood firm, refusing to budge for almost two decades while Evangelis’s one million drachmas languished in the bank.

In time the authorities, abandoning all hope of wresting the barley field from its owner, were forced to back down. They transferred their efforts to another site, very near today’s Zappion. The issue, however, was not to be resolved so simply and they soon found themselves floundering in yet another controversy. The newly delegated spot was the location of the ruins of some ancient Roman baths, which, in mid-nineteenth-century Athens, served a very utilitarian function. Few dwellings or buildings in Athens were then equipped with plumbing and it was the habit of many Athenians to repair, when in the area, to the public facilities provided by the Roman ‘baths’. Needless to say, when the news broke that these artifacts were about to be razed, self-proclaimed archaeologists, many of them among the ‘baths’ habitues, raised a storm of protest at this planned desecration of an archaeological site. Pronouncements by experts that the baths were of no real ‘archaeological’ value, and that their social function could be easily transferred elsewhere, fell on deaf ears and the Government was forced to look for a new location.

This they did, settling on the area now known as the Zappion Gardens. The cornerstone was finally laid in 1874 by King George I in the presence of Konstantinos Zappas. By then, King Otto had made his ignominious departure from Greece in 1862 and Evangelis was long since dead.

Although the building had remained locked in stubborn controversy for two decades, during the interval Evangelis’s dream of reviving athletic events along the lines of the ancient games had not been neglected. They had in fact materialized, although not quite as he had envisioned them. The national sport of nineteenth – century Greece, odd as it may seem, was stone – throwing, both on an informal and organized level, the ancient concept of athletics having faded over the centuries. Children as well as adults participated, and major stone-throwing events — perhaps a match planned between neighbourhoods — were announced in advance in the newspapers, and avidly followed by all but the most timid citizens. Although it can be argued that this sport may have evolved from ancient discus-throwing, this was hardly what Evangelis had in mind when he envisaged a revival of the ancient Olympic Games. Not only were other sporting activities neglected in Modern Greece, they were actively resisted by members of a reactionary intellectual movement, known as the sofologiotati, who argued that athletic activity impaired the mental processes. Attempts to introduce gymnastics dated back to Otto who had issued a decree in 1834 ordering gymnastics for the schools, but this and numerous other attempts had come to naught. Gymnasiums were built, equipped, and opened by determined groups or individuals only to close under pressure from the opposition.

King Otto, possibly under pressure from the Zappas, had nonetheless determined that athletic events should be organized, and that the other aspect of the agreement with Evangelis be honoured. Together with a German gymnast by the name of Ottenorf, he had made plans for the first modern Olympiad. The event, unsung in the annals of history, took place in 1859, almost thirty years before what careless historical accounts refer to as the first Olympiad.

Although most of the participants were conscripted from the ranks of the local cast-offs of society, beyond the reach of the weighty intellectual arguments of the sofologiotati, there was some international representation. The greatest triumphs were enjoyed by Maltese porters who carried off all the laurels in the track events. Normally employed as rickshaw runners, they were able to train for the Games on the job. Greece, however, won the rope climbing event when a beggar made it to the top first. The fact that he could see out of only one eye undoubtedly obscured the danger and aided him on his way. There were no equestrian events such as those we have grown accustomed to — and certainly no British princesses to participate in them — but horse races were held with the entry of horsedrawn-cab drivers of Athens, who had unhitched their steeds for the occasion. Thus, albeit in a modest way, part of Evangelis Zappas’s dream had been fulfilled.

Once the cornerstone was in place, what is more, plans for the building’s construction proceeded with haste. Indeed, fourteen years later, on October 2, 1888, the Zappion was opened to the public. King George I was not only still around to preside at the sequel to the cornerstone laying, but was celebrating that year his Silver Jubilee. As part of the pomp and circumstance of his anniversary, he would inaugurate the Zappion. The building itself was completed and ready for the great moment, but the grounds surrounding it were not. To allow His Majesty to be greeted by a veritable wasteland would have been unthinkable, but this turn of affairs would not be allowed to cast a shadow over the occasion.

And so it was that when the King and the good citizens of Athens arrived at the Zappion for the inauguration, the building was surrounded by what one newspaper called ‘Le Jardin a la Minute’. Potted plants, bushes and even trees had appeared overnight, transforming the grounds into a garden worthy of Versailles.

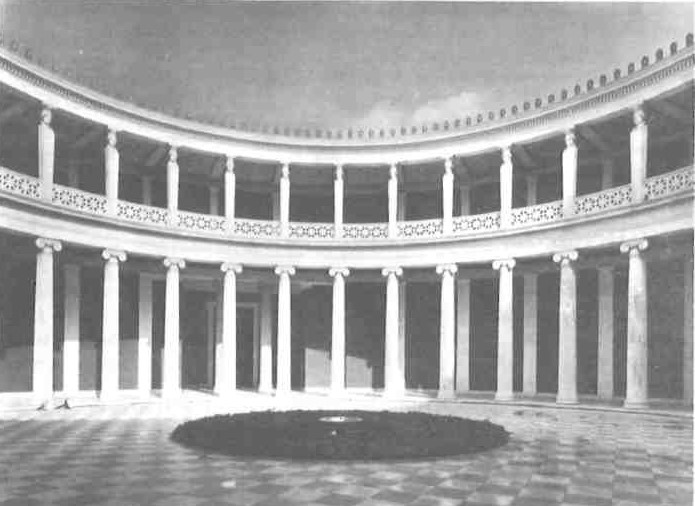

The long-departed Evangelis was not present, of course, but he had not been forgotten. Near the entrance, a casket containing his heart had been incorporated into the building so that his ‘heart and soul’ might be preserved, a tribute to his dedication. Nor was Boulanger, the architect who had drawn up ‘the original plans, in attendance, but perhaps it was just as well. Boulanger had conceived of a building sitting on a knoll of the barley field and architecturally incorporating the nearby ancient stadium. After its many moves from one location to another, certain modifications had, of course, become necessary. Fortunately other renowned architects were to be found in Athens at the time. (As a matter of fact, famous architects were to be seen everywhere in Athens during the last century, since an extended stay in both Athens and Rome studying the ancient buildings was considered an essential part of one’s training.) Finally, exasperated by the delays, Konstantinos Zappas had called in Theophil von Hansen, the designer of the Academy and Library of Athens, as well as the parliament of Vienna, who completed the building according to his own plans.

A few years after the Zappion’s inauguration, work began, not far away, at the site of the ancient stadium. There, in 1896, the first Olympiad was officially proclaimed at the restored ancient stadium. We can only speculate as to what Evangelis would have thought. We would venture to guess that he would have been pleased and taken quiet pride in his own foresight. As for the Zappion itself, we suspect that it must have observed the fanfare with a heavy heart as it stood, and still stands, on the spot to which it was finally relegated, seeing history pass over its ambitious beginnings. Had it not been for a stubborn landowner and equally stubborn Government, after all, it might have been sitting up there in a commanding position on the little knoll as the modern Olympic Games finall> got underway, there to preside as the Sacred Flame arrived from Ancient Olympia to announce the beginning of yet another Olympiad.

Information for this article is drawn from The History of Athens (1973) and Athens of the Previous Century (1963) by historian Epaminondas Stasinopoulos.