Although their artistic value has been somewhat neglected, they are being increasingly used in many homes and resort hotels because of their utilitarian value and aesthetic charm. In Lindos, on the island of Rhodes, there have recently been sporadic attempts by artists to revive hoklakia as an art form, incorporating heraldic and zodiac motifs, or abstract patterns, in their designs.

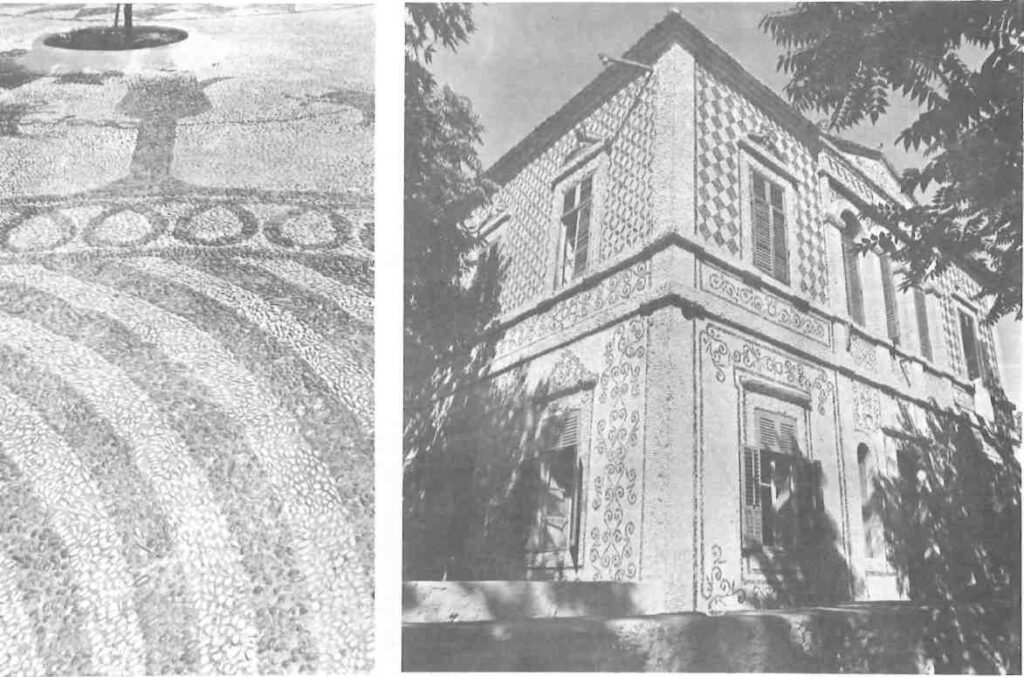

Hoklakia floors are long-lasting and almost indestructible. The pebbles, set in low relief in cement, are attractive whether in solid colours or patterns. In the Aegean world of shifting, high winds, arid, dusty summers, and near-tropical downpours, hoklakia provides welcome sturdiness. Practical in and out of doors, it can be used on small or monumental scales. In earlier centuries, the exteriors of houses were sometimes covered with these pebble mosaics. In Lindos, patios, courtyards, bedrooms, kitchens, bathrooms, sitting rooms, and even the nearby streets may be a flowing series of hoklakia, providing a continuous harmony between indoor and outdoor spaces, and laid in such a fashion that the entire house and courtyard can be swept through in a single continuous operation.

Although the name hoklakia — a corruption of the French word for shellwork, coquillage — dates back to the Crusades and the Frankish presence in this part of the world, the technique originated in prehistoric times. As an art form, however, hoklakia reached its greatest heights in the palaces at Pella, the ancient capital of Alexander the Great’s Macedonian Empire. When Pella was located in 1957, excavations brought to light the pebble mosaic scenes of the Lion Hunt and depictions of mythological scenes. Housed today in the museum across from the ancient site, these mosaics are considered among the treasures of Greece.

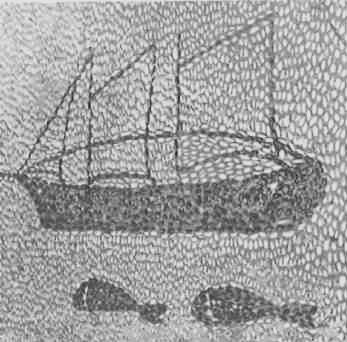

The great figure scenes of the pebble mosaics of Pella are no longer favoured. Over the years patterns have evolved in accordance with changes in taste, and the size and colour of available pebbles. During the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries craftsmen used eight centimetre pebbles. The patterns, more often than not in black, brown, and grey hues, were of boldly outlined ships, trees, coffee-pots and geometric designs such as circles and stars. In the nineteenth century, chevrons, zigzags, sundial-like centrepieces and wide or narrow bands of black on white, were popular.

Today’s craftsman carries, it seems, a stock of patterns in his head. Pebbles used in more recent mosaics range in size from tiny jewel-like stones to those eight centimetres long, but pebbles of three or four centimetres are the most widely used. Buffs, browns, and blacks in solids or combinations, and black and white patterns predominate.

Laying hoklakia is slow work. A craftsman and a helper working together can lay only two square metres a day. The pebbles, chosen for-size and colour, are collected from various beaches, graded by expert gatherers, and separated according to size and shape. The pebbles are eventually laid in mortar in long lines of uniform-sized pebbles in neat, parallel rows.

The procedure for floor-laying is prescribed by tradition. Earth floors are roughly levelled, smoothed and packed down. Then the mortar — sand, whitewash or, more recently, cement — is poured, to a depth of five or six centimetres. It is then carefully graded and allowed to set hard. When the craftsmen are ready to set the pebbles in place, the floors are divided into the width of a man’s reach — which is as much as can be laid in one day — and the area is marked off with wooden strips. The final mortar is poured to a depth that will cover about three-quarters of the pebbles when they are set in place. The pattern is scratched into the mortar with a sharp nail, and the pebbles are laid along these guidelines. When the design has been completed, the background is filled in with pebbles, usually white, in such a way as to allow for drainage slopes. Once this stage has been completed, the pebbles are tamped down to their final position; the top quarter of each pebble is allowed to remain above the mortar and surplus mortar is scraped away. The process is repeated until the entire floor is covered.

Many examples of hoklakia can be seen in public and private places in the Aegean: in houses, hotels, and church courtyards — or at seaside quays such as on Hydra. Most unexpectedly, Rhodes workmen have set up hoklakia floors at the United Nations headquarters in New York. But mosaic pebble floors have more or less been superceded in recent years by the use of flat, square or triangular tiles and mosaiko (chips of marble embedded in coloured mortar and polished to a high gloss). Yet among the choices of floor coverings available, hoklakia are among the more attractive alternatives. Its low relief texture will set off flat, white-washed wall surfaces and garden foliage. With a renewed interest now in popular crafts, hoklakia is perhaps on the threshold of a new era in its long history.