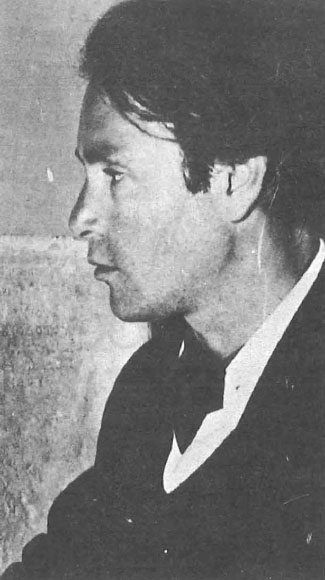

Yanni Christou, the son of a wealthy Greek industrialist, was born in Egypt in 1926. He studied in England and won a degree in philosophy at Cambridge in 1948. This study later proved to be the basis of his compositions, as he believed that a philosophical – metaphysical background was necessary for creating great art.

While pursuing his interests in philosophy, he was also studying music with Hans Ferdinand Redlich, who had been a pupil of the composer Alban Berg. Christou also studied composition and orchestration in Italy for several years before returning to Egypt where he lived until 1956. In that same year he married Therese Choremis, who was from the island of Chios. They moved there in 1960, settling in a country house on a large property. Christou worked in peace, surrounded by a rich library devoted to philosophy, religion, anthropology, psychology, history, literature, art, music, magic and the occult. During this time, his musical ideas fermented. The musicologist John Papaioanou has written, ‘Christou’s preoccupation with metaphysics and transcendentalism, myth and magic, mysticism and Oriental religions, underlined by his extremely large collection of books devoted to such subjects, gives a particularly intense and deeply moving colouring to his music. He is the only Greek composer who stands so firmly astride East and West.’

When the house and property were expropriated by the government to make room for a new airport on Chios, Christou, feeling a need for a less isolated life, moved to Athens with his wife and their three children. He planned, however, to develop a kind of cultural resort on a large estate in Chios, where music and drama festivals could be held. These plans were never fulfilled. On January 8, 1970, Christou and his wife were killed in an automobile accident.

Christou left behind music of great value, but it has seldom been heard. A perfectionist, he did not want his works played unless he was certain the performance would measure up to his strict standards of perfection. As this was hard to assure, he preferred that his works not be played at all. Phoenix Music and his First Symphony have been performed by the Athens State Orchestra under Paridis, and Litschauer, the Austrian conductor who headed the Radio Symphony Orchestra, devoted a program to his Patterns and Permutations. Like the audience that first heard Stravinsky’s The Rite of Spring’, this performance was received with boos, and catcalls, fistfights broke out between those who were willing to give the music a try and those who were determined not to hear it.

Even so, his work has slowly become known here and abroad. In 1964 the committee of the English Bach Festival asked him to write a Pentacostal Oratorio. This resulted in Tongues of Fire, an oratorio which has been heard in Italy as well as in England. His scores for ancient Greek tragedies, which have been performed by the National Theatre and the Art Theatre of Karolos Koun, have been repeatedly praised for their force and feeling.

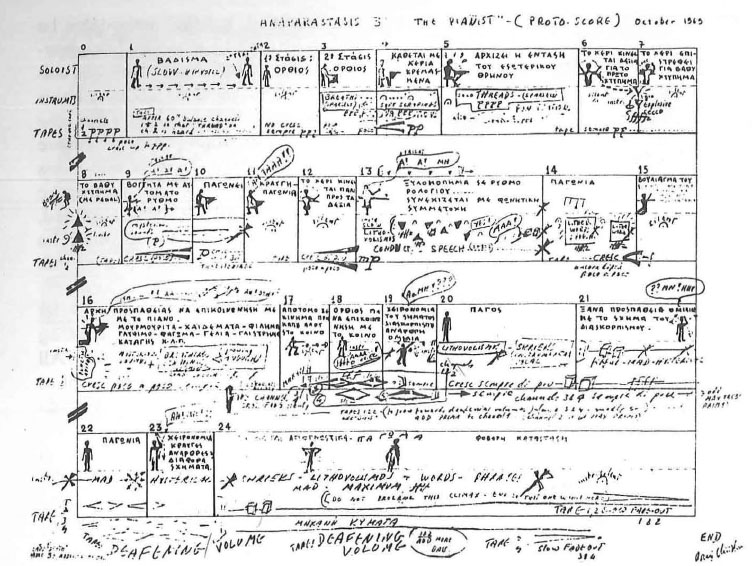

Christou considered Mysterion to be his best composition, a mixed-media work for the stage, scored for narrators, three choirs, tapes and actors. Its theme was drawn from ancient myths in the Egyptian Book of the Dead, Two gigantic projects, however, preoccupied him from 1966 to the time of his death. The first was called simply The Project’, involving a new system of writing music which he called synthetic notation. It was a free but precise method of notation which enabled him to score rapidly his musical ideas. The scores using this revolutionary method are, at first sight, incomprehensible to the uninitiated, but the method can be quickly learned by reasonably competent musicians. In fact, so concerned was Christou with the accessibility of this new system that he tried out the notations on his young daughter before making them final. If she could guess what any given notation meant, then he judged it acceptable. If she was puzzled, he would renew his search until he found a symbol she could understand.

One-hundred and thirty compositions were to be included in ‘The Project’ — grouped under the heading Anaparastasis (Re-Enactments). All were to include stage action as well as music. A formal theatre, however, was not needed for their presentation. He had envisioned his cultural resort on Chios as the best stage for the Re-Enactments, for which the ideal setting might be a village street and the ideal extras, local country people. A summary of about forty of these Re-Enactments survive, but only four have been written out. Each of these has a separate theme, related to a corresponding musical pattern.

The title Re-Enactments is symbolic. He intended to evoke ancient or primitive rites in which the participants perform as if in a trance or a state of ecstasy. For Christou these rites had a profound meaning because they were beyond the reach of the rational mind and sprang from deeper, hidden emotions. This, then, was his purpose in the Re-Enactments — to release the primeval urges common to man throughout his past.

The second major project which he believed would be a summary of all he had done thus far, and which consumed the last three years of his life, was a modern interpretation of the Orestia of Aeschylus. The world premiere of this work was scheduled for April 1970, to be followed by a world tour. Christou was killed in January. He had not completed transcribing this work, and all that the world is left with are brief jottings for a score which, although fully developed in his mind, is now lost to posterity.

Only three of Christou’s works were published during his lifetime. Now several of his colleagues and friends are locating and publishing whatever scores remain to be found. Those that have come to light are of stunning power. An album of Christou’s compositions, Late Works, which includes ‘Praxis for 12’, ‘Anaparastasis 1 and 3’ and ‘Epicycle 2’, is available in Greece and should be heard by serious students of contemporary music.