Finally I saw the white marble plaque on a wall at the corner of the narrow street. The carved message had been almost obliterated by wind and rain, but those familiar with the story would be able to decipher the legend:

ΟΔΟΣ ΜΑΗ ΦΡΑΙΗΖΕΡ

May Fraser Street. Those words brought back memories of a gallant, frail figure that had stood tearfully regarding it on the day of its unveiling in 1963. Turning the corner, we came immediately to the chapel. A boy came running with the key and we opened the door.

‘Oh, God! How beautiful!’ exclaimed my young companion.

As the ship from Athens eased itself alongside the quay on the island of Chios, on that Saturday morning in March, 1963, hundreds of people awaited us. Juliette May Fraser stood with the Mayor of Chios. Beside her was David Asherman, her companion and assistant, and other distinguished Chiotes there to welcome officials and guests. Among them were the parliamentary deputy for Chios and the Director of the United States Information Service. The Admiral of the Sixth Fleet, which was then in Faliron Bay, had dispatched a destroyer, the USS John King, on an official visit to coincide with the event.

May Fraser, a native of Hawaii and the first foreign artist ever to decorate an entire Orthodox religious edifice in Greece, was formally to present her murals to the villagers of Vavili on the following day.

I had met David and May when they lived for a while across the street from me in Athens. Juliette May Fraser, one of Hawaii’s outstanding artists, was born in Honolulu in 1887 when the fiftieth American state was still a sovereign kingdom. After graduating from Wellesley College in Massachusetts in 1909, she studied at the Art Students League in New York and at Woodstock School as well as at the University of Hawaii and the Honolulu Academy of Arts. She has worked extensively in oil — nearly a dozen one-man exhibitions have featured her works which are represented in the Smithsonian Institution, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, and others. Her book, Ke Anuenue, published in 1952, was selected as one of the Fifty Best Books of the Year by the American Institute of Graphic Arts. Her major work, however, has been in the media of murals and frescoes. She painted her first mural in the 1930s, and in 1939 executed the mural for the Hawaii building at the San Francisco Golden Gate International Exposition. Many others are now on the walls of public buildings in Honolulu, including St. Andrews Cathedral, the Hawaii State Library, and the University of Hawaii. Not long before her arrival in Greece, she had completed a ninety-two-foot mural for the Mid-Pacific Institute.

She has been described by intimates as a ‘one-man army’ when there is work to be done, yet she is unassuming. ‘When I think of her, I think of honesty, shyness, gentleness, and service to others,’ Edward A. Stasark said in 1960 when he was President of the Honolulu Print Makers. David Asherman, himself an artist and at the time President of Hawaii’s Painting and Sculptors League, has said, ‘Each excursion she makes into the world beyond Hawaii renews her inspiration. Despite her monastic life, her paintings contain the wonderment of childhood.’

It was during the time they were living in Athens that May and David decided to go on a hiking tour to Chios to visit the famous eleventh-century Byzantine mosaics in the Church of Nea Moni. It was Holy Week. On Good Friday morning they had come upon the bare little chapel in Vavili, its whitewashed walls undecorated because of lack of funds, explained the church treasurer, Kyria Aphrodite Makris. May and David had continued on their way, carrying with them memories of the little chapel whose blank walls emitted rays of appeal to the artists. They soon returned to Vavili and told Kyria Aphrodite that they were prepared to paint the walls of the chapel if the expense for paints and plastering were borne by the congregation. They did not, however, expect to be paid for their work, which they were offering ‘as a gift of friendship from Hawaii to Chios’.

On the Saturday after the official reception and luncheon that marked the arrival of the dignitaries from Athens, while the others took their siesta, I went with David and May to see the chapel. The little village, with a population of two hundred, lies on a hill half an hour from the town. It had been completely destroyed, David explained, by an earthquake in 1881, the most destructive that Chios had ever suffered. The villagers had rebuilt their homes and their church. It was not until 1961 that they had collected enough money to erect a small chapel on the site of the old one which they rededicated to the Presentation of the Christ Child to the Temple.

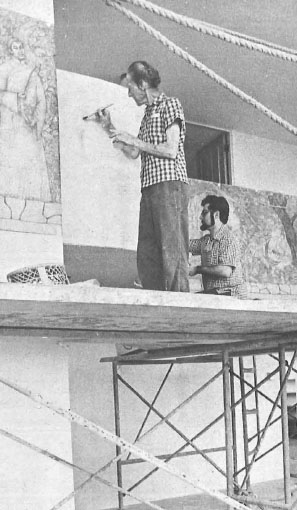

The tiny chapel in Vavili stands on a knoll. Its exterior was lacking in grace and in an effort to soften the harsh effect, David Asherman supervised as one of the local artists decorated the walls with graffito, adding a touch of Chiote folk art to the building. To bring this exterior into colour harmony with the interior, the bright colours of the murals were used outside on the dark-grey background of the incised geometric design.

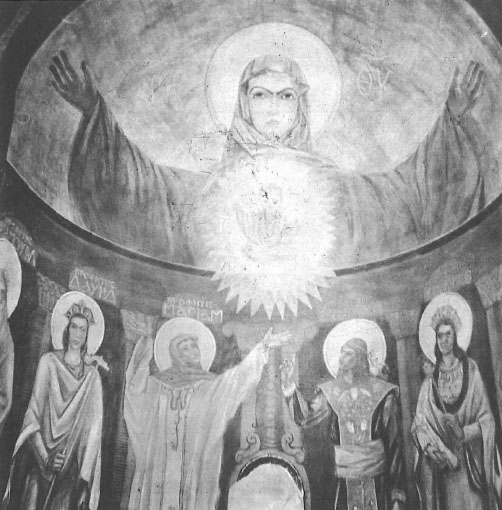

When we arrived at the chapel, I was surprised and delighted as I stepped into the tiny, radiant interior. Buoyantly exciting in a way that Byzantine art never is, the icons, David assured me, were nonetheless in proper Orthodox style and tradition: The Virgin and Child were in their correct location in the half dome over the altar; the Eye of God was on the flat wall above flanked by the Archangels; the four Evangelists, lacking their customary pillars, were placed in the niches of the two windows, and all other requirements and disposition of Saints had been met. ‘It’s a rather unorthodox dragon that is attacking St. George… from the sky instead of from the ground,’ David confessed and, indicating the beautiful icon of the Annunciation over the door, noted that the setting was a Vavili courtyard.

When I expressed my surprise that the villagers accepted the brilliant colours and un-Byzantine poses and vestments of the Saints and Angels, David assured me that they had not only accepted the frescoes, but were wildly enthusiastic about them. This was indeed the case when I spoke to members of the congregation the next day.

May Fraser had spent many months researching Byzantine painting and Orthodox tradition before undertaking her work. She had visited churches in Greece and Yugoslavia, and David had gone to Mount Athos. She had remained true to the rigid requirements of the Greek Orthodox Church, David explained, noting that each important line and form was to be found in some great Byzantine icon, as well as many of the details. With a smile he added, ‘But there’s still a good deal of May present. Look at that helmeted angel garbed as a Hawaiian chief, blowing a conch shell instead of a trumpet,’ he said, pointing to Gabriel. ‘May felt she must put in something to tie Vavili up with Honolulu.’ On closer examination I found coconut palms, pineapple plants, and other Hawaiian details. ‘The villagers immediately identified the helmet as an ancient Greek one, and the conch shell as a Chiote fisherman’s signal horn. Just local stuff,’ David told me.

Since the chapel had been dedicated to the Presentation of the Christ Child, May’s choice of the themes of youth and joy for her murals was a happy one, suitable to her luminous palette. She had searched records for references to Christ and the Virgin, to Saints and Prophets in their youth. Wherever possible, she had portrayed them as young. Her choice of brilliant, unexpected colour charms the eye and lifts the heart. The lines are precise, the subjects graceful and reverent, without the austerity and solemnity of Byzantine painting. The murals are an expression of childlike faith in the goodness of mankind.

She had spent nine months working on the murals, getting up before sunrise. In winter she had sloshed in rubber boots through the last mile to the village past the point where the bus could not go any further. Wearing woolen gloves with the fingers cut out to protect her hands from the cold in the unheated building, lying on her back on the scaffolding to paint the host of angels, cherubs, birds and other details on the barrel-vault ceiling, she had worked seven days a week and, on fresh mortar days, continuously into the night by the light of candles and kerosene lanterns. An amazing achievement for anyone, yet for the seemingly frail May Fraser, who was then in her seventies, it was the manifestation of remarkable dedication of spirit. (Her eighty-fifth birthday, ten years later, would find her once again high on a scaffold painting a twenty-six foot long mural in Honolulu.)

At the chapel the following day, the ceremony was attended by the entire village. With Greek and American flags fluttering in the breeze, and the brilliant red, renowned, Chios tulips carpeting the grounds around the chapel, the dignitaries gathered, and May Fraser presented Vavili with her gift to the accompaniment of speeches by the Deputy of Chios, and greetings from the American Ambassador, the Mayor of Honolulu, and from Hawaii’s Congressman. The formalities over, the villagers, in a surprise ceremony, announced that they were naming the little street leading to the chapel after the artist, and unveiled the plaque with her name.

‘We thought,’ replied the artist in faltering tones, ‘that in decorating your chapel we were giving you something. But we soon found that we had received much more. You gave us your hearts and made us feel that we belong here. Now you have made that bond an everlasting one.’

When I arrived last year, an iron railing surrounded the sadly weather beaten graffito walls. When we asked children playing in the street for Kyria Aphroditi, they told us she had died. Seeing strangers, a boy ran up to us with the key. We entered the little chapel. The holy lamps were lit before the main icons. The figures of Jesus and John the Baptist, to the right of the entrance to the altar, and the Virgin Mary, to its left, have now been covered with ex-votos of engraved silver vestments. Although sanctification has been withheld by the Bishop, the villagers have continued to worship at the chapel. We lit candles and said a prayer for May and David.

A small crowd had gathered outside and we asked if many came to see the chapel. ‘Yes,’ a man spoke up. ‘Mostly young people with packs on their backs.’ Just as May Fraser and David Asherman had arrived the first time at the little chapel in Vavili.