She was fat and dressed in colourful but old clothes with so many patches that it was difficult to distinguish the original material. Her tsemberi, the scarf worn by peasant women, covered much of her face. It was wound around her head and neck in such a way as to create a brim that protected her eyes from the blinding sun which was at its high point that day late in July.

I addressed her. ‘Kalimera, Kyra Mitsena.’ She raised her folded body, threw back her head and stood up straight among the green plants in her perivoli, the section of land allocated to her and her husband.

‘Kalimera, she replied. ‘How are you? You must be Kyra Eleni’s daughter,’ she said as she came towards me. We shook hands, the rough skin of her palm scratching against mine. She had a full-moon face. When she laughed, her eyes almost completely closed and her lips unveiled a series of black and tarnished teeth.

‘Have you been here long?’

‘No, I arrived from Athens half an hour ago, and I’m anxious to see the property and the beach. How are the prices of vegetables this summer?’

As we chatted, a thin boy, wearing shorts and a tattered red shirt, carefully stacked tomatoes in the wooden cases. Between each layer he placed a vivid pink sheet of paper. He continued his work ignoring my presence. Only once, after he had made certain that his mother wasn’t watching, did he cast a hasty glance in my direction. I smiled at him but he immediately looked down as he continued his taciturn work.

‘You know, Kyra Katerina, tomorrow is the Friday pazari and we are preparing the loads,’ she explained, referring to the weekly market at the nearest town where they sell their produce. ‘Mitsos will take them early in the morning, so everything has to be ready today before dark. Prices are high for early tomatoes. Look at this,’ and she offered me a round, glittering, plump tomato, its deep-green stem still attached. ‘It tastes just like meat.’

Mitsos is the nickname for Dimitris. His wife is called Mitsena; that is, the wife of Mitsos. This is the custom. The wife of a Yannis is known as Yannou, or Yiorgos as Yiorgena. A woman belongs to her husband; she is his possession. I don’t know Mitsena’s family name, nor her first name, for that matter. Mitsos and Mitsena—Mitsos and Mitsos’s wife — are how her husband and she are known throughout the valley.

At that time they cultivated a section of our family property. It is in the Mani, that rocky, barren area of the Peloponnisos that reaches out between the bays of Laconia and Messinia. About twenty stremata in size, the property begins on the main road and ends on a sandy beach. Rows of tall cypress trees run along both sides, creating a natural fence which separates our land from neighbouring fields. There are about four hundred olive trees on the property: one hundred and fifty with small, dark leaves whose olives are pressed to make oil, and two hundred and fifty with large silver and deep green leaves whose olives are cultivated for the table.

Mitsos’s small allotment was in the middle of the property extending on both sides of the wide path that leads to the seaside. He did not pay rent. He sold the produce he grew and in return for his use of the land, we received, throughout the summer, freshly cut vegetables of all kinds: tomatoes, squash, eggplants, okra, green peas, celery. He also looked after the olive trees. His sons pumped water from the well through metal pipes to the roots of each tree. These olive trees are privileged in comparison to the ones in the interior of the Mani; they are usually small with twisted trunks because the only water they receive is from the rains.

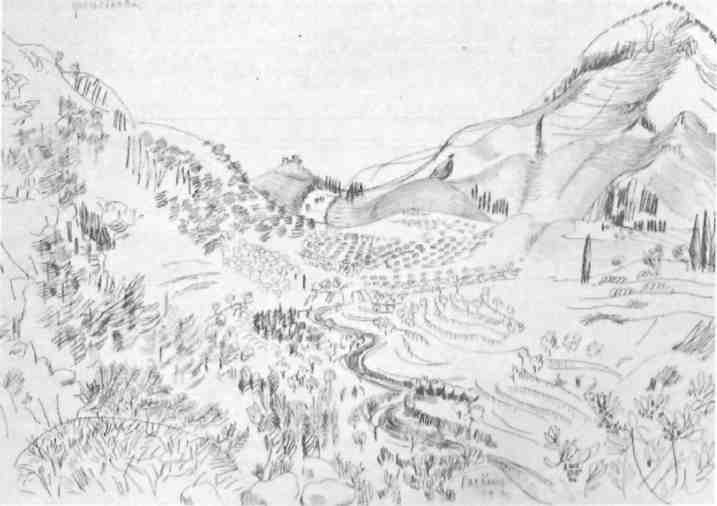

The little village of Mavrovouni, perched on top of a hill at the entrance to the valley, gives its name to the ‘Kambos of Mavrovouni’. Looking toward the north, the Taygetus range can be seen.on the horizon. Small houses are scattered in the valley which, to the south, ends at the beach.

Life in the valley and up in the village continues at the same pace all year, from one season to the next. The young boy or girl that last summer was tiny and shy, this summer is a young man or woman still shy but ready to conquer the world. Nothing else changes very much. The world is enclosed between the mountains and the sea…

WHEN Mitsena was a young girl, she was given to Mitsos by her parents. Her family lived in another small village in Mani. He was from the nearest town, had some relatives in Athens and owned a small piece of land. As customs go, it would never have been left to the young Mitsena to choose her own husband. This is a decision made by the father.

Mitsos could never have been attractive. He is not more than five-foot three-inches tall, and very thin. His head is bony and fleshless so that the skin seems glued to his skull. His smile is a blend of shyness and bitterness. His eyes, red and tired, reflect embarrassment and cunning. His ears are prominent and they emphasize his naive face. They are his most distinguished feature.

Once married off, Mitsena immediately lost any illusions she might have had about married life. She plunged into work, interrupted only briefly by the births of her children.

There are five. The first three are boys: Yiorgos, Thodoros, Petros. They have dark hair, dark eyes and darker skin. The two youngest are girls: Sofia and Polytimi. Polytimi is beautiful and does not seem to have anything in common with the other members of her family. She is blond, with green eyes and a full mouth with deep-red lips.

Mitsena gets up at five o’clock every morning and attends to her household chores. Around seven, she takes her white goat and makes her way to the property. She ties the goat to a wooden stick, far away from the olive trees which it might be tempted to feed on, and begins her work.

Work in the fields never ends. Once the soil has been well ploughed, it is separated into ‘beds’ and then sowed. When the first green leaves of the plants appear, they are separated and transplanted. Each is fertilized, and unnecessary leaves are removed so there will be more strength for the fruit.

Most of the work is done by Mitsena. Petros is very young and helps in secondary work. The two older boys look after the black horse, Arapi. (Mitsos once had a beautiful white horse, but some years ago, when tomatoes were bringing a good price, Mitsos thought that he would hazard his ‘lazy’ chance. He lost the horse at cards.) Mitsos meets his friends every afternoon at the little grocery-coffee shop at the corner of the main road. They play cards every evening under the over-hanging vine and they listen to the day’s gossip.

Yiorgos, having completed the six compulsory years of school, helps his father work the little field which belongs to Mitsos. They do not realize much from the crops of this land, and seldom go there. Situated in an area of the valley exposed to the north wind which blows from Taygetus, it is barren and during the winter almost constantly covered by a film of ice.

Mitsena, however, goes there at least once or twice a week accompanied by her two daughters. This is in addition to the work she usually does in the allotment. They walk the five kilometres back and forth.

Sofia, the older girl, does a little cooking at home, sews patches on the family’s clothing and does the laundry. She and her sister are often seen wearing dresses in pastel shades, elaborate with embroidery and lace, and very much out of keeping with the environment. The dresses are sent from the United States and the local bishop distributes them. After the first day of use the dresses are stained by the soil and plants. The two sisters go barefoot; their tiny feet are earth-stained and tough enough to be insensitive to pebbles and even thorns.

At noon the family gathers under the shade of an olive tree. They spread their frugal lunch on the ground. Tomatoes accompany every meal, constitute the hors d’oeuvres, add to the main dish, and take the place of a sweet or fruit. They devour them, straight from the plant, without washing them to remove the fertilizer.

After lunch Mitsos usually takes a short siesta under a tree, using a pile of reeds or a stone as a pillow. The boys resume work and the girls follow their mother into the house where Mitsena has many things to do in her primitive little household. In the afternoon she returns to the field where she continues her labour until dark.

Once or twice a year Mitsena takes a trip to Kalamata where she visits her sister who lives there with her own family. Mitsena’s brother-in-law is a truck driver and she is very proud of him since he is not a slave to the land. She returns to the valley happy, always with a new dress that she has bought there. She is always excited before, during, and after the trips, the major event of her summers. In general, however, every day is identical to the day before or the day after for Mitsena, and for the women in the valley and up in the village, who toil from dawn to dusk.

Mitsena is an observer of her own life. She is passive. Life can be different for others but not for her. It is hard labour that never stops, until the last years of life. Child-rearing does not interrupt it for long since it is limited to the first two or three months of a child’s life. After that, the older children look after their younger sisters and brothers, unravelling any difficulties that arise as well as dealing with the minor, everyday problems. They feed them and supervise their first steps.

Working in the fields devours most of Mitsena’s days and those of the other women. With some exceptions, it is there that their babies grow up, under a fig tree, next to the goat, near the mother toiling close by.

WHEN I arrived in the valley last summer something had changed. The family had moved from the small house they rented on the beach and no longer worked the plot on our land. The year before, the crop had brought good returns and they had moved to new quarters located above an old oil press, at the edge of the road. They had bought a refrigerator. Mitsena, it was said, had boasted, ‘Now I have a house appropriate to accommodate any visitors.’

The new house does not have running water, but it has other advantages. Since it is on the main road, Mitsena and the children can watch cars and mules and men passing by. What is more important, the passersby may see and admire the new blanket that Mitsena bought on a trip to Kalamata, hanging on the window. The two girls have new dresses now, not the American ones from the bishop, but their own, brand new ones. And Petros, the youngest boy, is delighted with his new shirt. Thodoros has a pair of shoes. As for Yiorgos, he can now afford to go to the open air cinema located in the valley on a Saturday night, or even into town.

Mitsena works as hard as ever. The girls are older and help more in the house. The plot behind the new house, however, is larger than ours and she spends more hours among the vegetables.

Mitsos complains that competition from the town merchants is unfair. They have vehicles and buy the valley’s products at very low prices and resell them at the villages in the region, at much higher prices. Nevertheless, he feels rich enough to be at ease about the payment of the little debt he owes the bank. And he still finds the time to join his friends at the small grocery-coffee shop where he plays cards for hours on end. Sometimes he dreams of selling Arapi and buying a tractor. Then he, too, would be able to go around to the little villages selling his own products.

Mitsena will then have even more work in the fields. Otherwise, life will continue as before for Kyra Mitsena and for the women who toil from dawn to dusk in the valley and up in the village of Mavrovouni.