Once away from the exhausts of Athens, to speak of weather is to invoke the winds. Temperature almost seems irrelevant: visitors to Greece want uninterrupted calm, bounatza, the better to enjoy the pellucid Greek water, while the farmer longs for a cool offshore wind to comfort him’ in his daily work, from threshing and winnowing in June and July to winemaking in September. A wind, however, short of a storm — a fourtouna.

Although farmers, and even town-folk, are eloquent on the subject, if you want to cull expert opinion on Greek winds you must fraternize with fishermen. When the sea is foaming and their wide-bottomed caiques are safely moored, they have little else to do but discuss the winds, the possibility of their increasing or abating, their direction, their treacherousness. Preferred is a slight northerly or northwesterly breeze — typically June weather — when, according to the fishermen, the fish bite. Then they can range in their little caiques quite far, the larger caiques staying away for perhaps several weeks during which the crew eats nothing but fish, and works nearly twenty-four hours a day. Every ripple of wind and sea is sagely commented upon in an attempt to pierce the winds’ ultimate inscrutability.

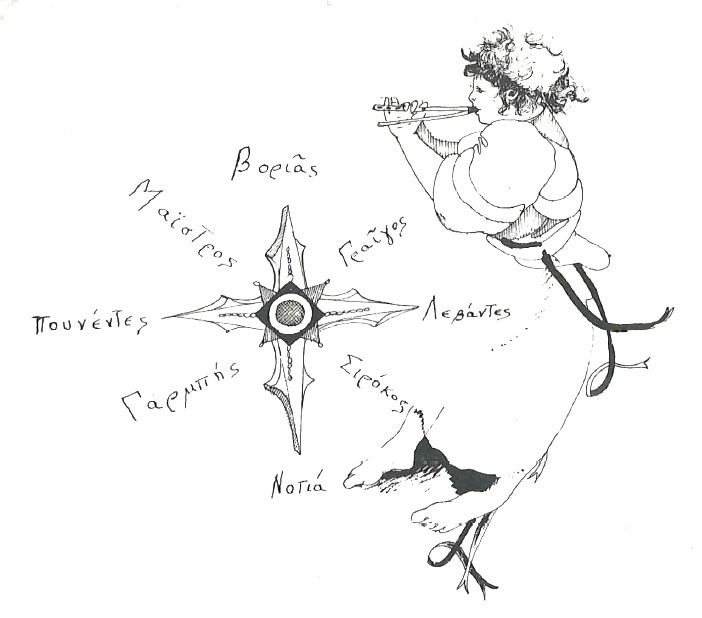

There are many local names for the Greek winds; those given here are commonly heard in the Cyclades, where many classical forms have been preserved. The most renowned wind must surely be the north wind, the Vorias. (In the Peloponnisos the Italian word, Tramountana, remains in widespread use, no doubt a vestige from when Venetian sailors were masters of Greek seas.) The ancient god Boreas — Vorias is the modern pronunciation — married the daughter of King Erectheus (of Athens’ Erectheum) and so became son-in-law to the Athenians. On ancient vases he is depicted with rough hair and beard, carrying off his bride. He is one of the four cardinal winds Homer mentions, which caused such havoc when loosed by Odysseus’s suspicious crew from the bag which the Lord of Winds, Aiolos, gave the wily captain, containing all except the favourable west wind. On the north face of the octagonal Tower of the Winds in the Roman Agora in Athens, he is shown about to blow into an elegant conch shell. He is benevolent, for the Vorias is cool in summer and in general, salubrious, even in winter. When the wind goes over force seven — and this can happen with startling suddenness, justifying the Greek seas’ reputation for hazard — and keeps the boats embayed, the Vorias is often the boisterous culprit. Hesiod, the eternally pessimistic poet of the eighth century BC, gave, in the Works and Days, the following warning: ‘Watch out for the month of Lenaion, bad days that would flay an ox. Watch out for the frosts which Boreas, the northwind, cruelly causes as he sweeps over the land. He gets his breath and arises on the open sea by horse-breeding Thrace, making earth and forest groan.’

The Vorias’s immediate neighbour, the northwesterly Maistros (the French call it Mistral), is a common wind of late spring and summer, although when it blows thus seasonally it is given the specialized name of Meltemi. It is cool and dry, characteristically abating at dusk and rising again at dawn with renewed vigour. Farmers consider it the ideal wind with which to winnow their grain which they toss with wooden pitchforks into the air for the helping wind to carry off the weightless chaff while the heavier grain falls back onto the stone threshing-floor.

Today the west wind is called Pounentes, though the ancient name, Zephyros, is still sometimes affectionately employed for this beneficent wind in its gentlest aspect. In the islands, this is a pure seawind, fresh and bracing, but brief, and likely to move either northwest to become a Maistros, or southwest to be called the Garbis. This latter is especially appealing in late winter or early spring, when it most frequently blows, for it is commonly a bringer of the warm rain needed by the shoots of young grain. The ancient Greeks often conceived of the winds as fertilizing, and the Garbis is still so considered.

Akin to the Garbis is the southerly Notia (the classical Notos), though it is somewhat less welcome than the former. It too brings rain and on the Tower of the Winds it is represented as a clean-shaven young man emptying an urn. In many places it is referred to as the Ostria (Latin Auster). The poet Seferis considered it enervating, as in the seventh poem of his great sequence Mythistorema: ‘On our left the Notia blows and maddens us, / this wind that strips bones of their flesh.’ And in the summer it is indeed to be regretted.

Should it even hint of a deflection to the east, a barrage of disgusted, apprehensive invective is sure to be hurled at it, for the southeasterly is the dreaded Sirocco (Sirokos), a word of Arabic derivation. This wind is considered to be unhealthy, depressing, debilitating, and bad for the crops, burning the green, grain shoots to a premature golden colour. It often carries from its origin in the desert furnaces of Libya a fine grit of sand, a scanty but driving rain, and a host of allegedly infectious African germs. A plausible scientific explanation for such vilification is that this hot, wet wind induces low pressure, which tends to similarly affect the spirit, as does the high pressure which is a gift of the Vorias. In Crete, ancient vendettas are likely to be revived. In the farmlands, the farmers watch in helpless rage while fruits and blossoms are ruthlessly knocked from the nearly prone trees. The fishermen are compelled to remain ashore, and tourists feel too listless to continue their perambulations. Although this wind blows most often in winter and early spring, on the rare occasions when it appears in June or July, the scorching temperature is made even more unbearable by humidity. Often village shops remain closed, their owners rightly anticipating few customers.

Its easterly neighbour is not nearly as pernicious, and, in fact, is shown on the Tower of the Winds as a young man laden with fruits and sheaves. It is named after its place of origin, and thus is called either Levantesor Anatolikos: which is Greek for anything easterly. It is fiercest in the Adriatic, and was a chief reason for the ancient Greeks never colonizing the east coast of Italy, preferring Sicily and beyond.

Our last wind, the northeasterly Gregos (literally, The Greek Wind) is also, in the islands, largely a wind of transition, and is merely a relative, in the minds of many fishermen, of the Vorias. It too can be coldly fierce.

Fishermen, far from the safety of shore, and sensitive to every insinuation and hint of change, have not found these eight classifications sufficiently precise. They have combined names for greater exactitude: Voriagregos for north by northeast, or Shokolevantes for east by southeast, and so forth.

Thus, Greece, especially on islands and mountains, is a land of winds. When the tourist sitting over an ouzo at an invariably windy seaside cafe, wonders what the weather beaten old cronies in the back are going on about so volubly, very likely it is the winds, a topic most worthy, and like the winds themselves, inexhaustable.