Last year Professor Vanderpool presented a paper entitled ‘The State Prison of Athens’ at the annual meeting of the Archaeological Institute of America in Washington. In this paper, excerpts of which we publish below, a theory is proposed which identifies the Poros Building as the prison of Socrates. It was not until last February that the significance of this paper was given any wide publicity. Quite suddenly the studious tranquility of the Agora was intruded upon by excited journalists, cameramen and television crews who finally got the news onto the front page of the London Times, and the Moon Mullins page of the New York Daily News.

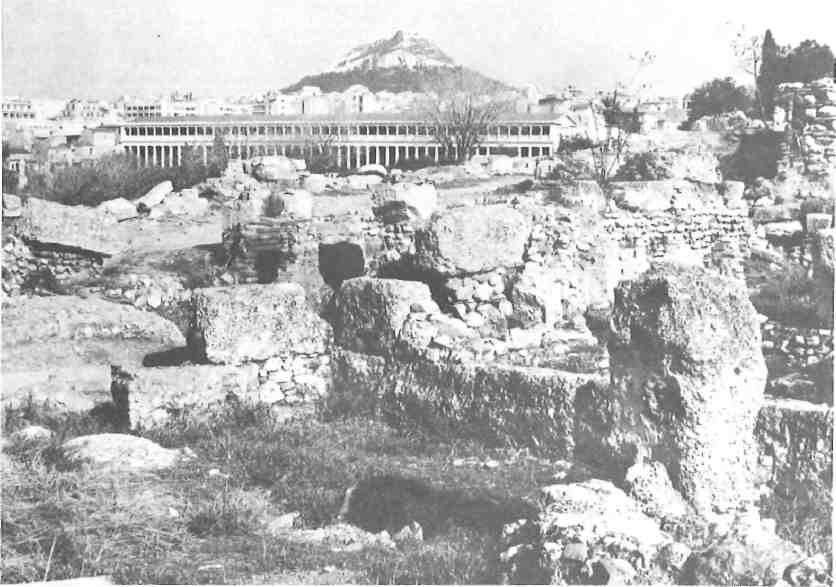

As Professor Vanderpool has warned, the site is anything but imposing as the building has been destroyed down to its foundations. A well-intentioned gentleman who wrote, in a letter to the Paris Tribune, that the site should be turned into an International Monument for Political Prisoners would certainly be disappointed by the odd bits of Roman wall and mosaic flooring that obscure the building today.

As a dramatic encounter between archaeology and human history, Professor Vanderpool’s paper is quite exciting – for it provides an unusual opportunity to see how the ancient texts, although far removed from our present, can shed some light on still-current mysteries.

Outside the Athenian Agora, to the southwest, a valley runs from the Tholos up in the direction of the Pnyx. This valley, excavated in the late 1940s, proved to have been occupied in Classical times chiefly by private houses and small workshops. In the midst of this residential and industrial area there was discovered a building larger and more solidly constructed than its neighbours with some large squared blocks of poros in its foundations. This came to be known as the Poros Building and was recognized from the start, from its size and its heavier construction, as a public building rather than a private one. The building right down to its foundations has been very badly destroyed. The poros blocks, which are its characteristic feature, are preserved at only a few points; elsewhere nothing but the pillaged foundation trench has survived. The site was built over in Roman times, and many of the Roman walls and mosaic floors are still standing, obscuring the outline of the original building so that the visitor to the site sees little or nothing unless he has a detailed plan of the ruins in hand.

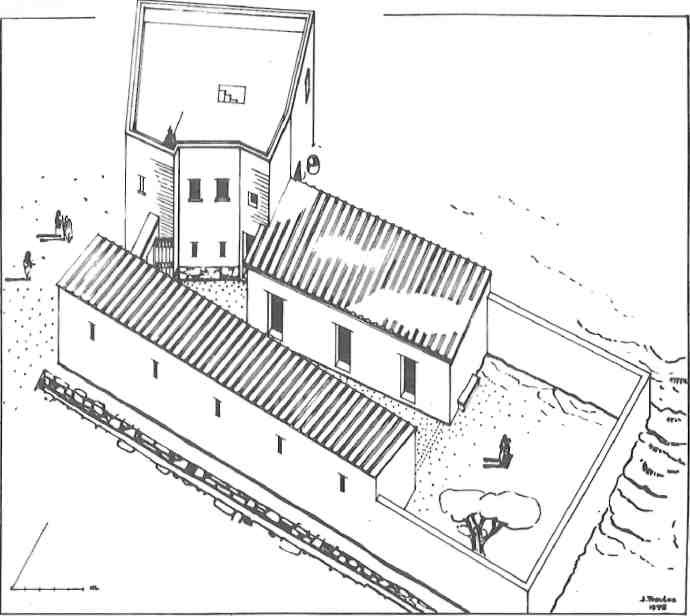

The building is a large one and of irregular shape. It consists of three main parts: a central section with rooms on either side of a corridor, a large open air courtyard at the south enclosed by a high wall, and a sort of annex at the northeast with four rooms set at an odd angle, corresponding to the bend in the street outside. This annex was probably a two-story structure as its walls are slightly thicker than those of the main complex, and there seems to have been a stair in the narrow space between the two southern rooms. The entrance to the complex was from the north where the building faces on an important east-west street which the excavators have named ‘Piraeus Street’, since it comes in from the Piraeus Gate. The entrance first leads into an irregular open area and then into a corridor which divides longitudinally this section of the building. This corridor was without a roof and there was a drain running the length of it. Opening off this passage were eight rooms, five on the right and three on the left, each about 4.50 metres square. These, of course, were roofed, and fragments of the Laconian tiles that covered them were found.

Little in the way of furnishings was found in any part of the building. The northwest room of the main complex had some simple arrangements for bathing: in a corner, a basin was found set down into the ground with its rim flush with the floor, an arrangement which recalls that found in bathing establishments. A pithos set deeply into the floor near the centre of the room probably held a supply of fresh water.

The building was originally constructed about the middle of the fifth century B.C. as indicated by the pottery found beneath the earliest floors which are of hard packed clay. There is evidence of remodelling in the late fifth or perhaps the early fourth century when the floor levels were raised considerably and the floors surfaced with marble chips to give a clean surface on which to walk. The building continued in use through the Hellenistic period with minor changes in plan until it was destroyed in Sulla’s sack of the city in 86 B.C. When the area was rebuilt in Augustan times, two private houses replaced the Poros Building.

The identification of the Poros Building has aroused considerable discussion, for it was recognized from the start that a building of such size and construction, of fifth century B.C. date, and located so near the Agora, should be a public building. The most favoured suggestion was that it was a law court, but this idea had to be abandoned because the form of the building did not suit the function of law courts as we know them. The idea that it was a synoikia or apartment building found even less favour. I should like to make a new suggestion as to the identification of the Poros Building, namely, that it is the State Prison of Athens, the Desmoterion.

The most famous prisoner of ancient Athens was Socrates, and the Platonic dialogues that describe his last days and hours give us quite a few bits of information about the location of the prison and about its furnishings. A few more facts can be gleaned from other authors. This evidence is, of course, well known and has been collected “more than once, but the picture that emerges from the literary evidence alone is neither very full nor very precise and does not enable us to say just where the prison should be sought or what sort of building it was. But now that we have postulated a definite location and a particular building, let us see how the literary evidence fits the case.

‘We used to meet at daybreak,’ says Phaedo, ‘in the court where Socrates’s trial took place, for it was near the prison. Every day we used to wait about, talking to each other, until the prison was opened, for it was not opened early. When it was opened we went in to Socrates and passed most of the day with him.’ It is now well established that there were several law courts in the Agora, including the Heliaia, and it is most probable that Socrates was tried in one of these, perhaps in the Heliaia itself. The Poros Building, which is just outside the Agora, could be described as near any law court in the Agora — and the nearest is the Heliaia. Furthermore, Plato in another passage where he is describing the ideal state says that the general prison for the majority should be near the Agora. (Vitruvius likewise says that the prison should adjoin the forum, and the Mamertime prison in Rome is in fact so located.) Finally, when in 403 B.C. Theramenes [the Athenian politician and military commander] was taken from the bouleuterion by the Eleven, he was led by way of the Agora to the place where he was to drink the hemlock, that is, the prison. The Poros Building, which is just outside the Agora, thus meets the requirements of the sources in respect to general location.

The prison must have faced on a wide street, for in May of 318 B.C., when the Athenian general Phocion and four others were in prison drinking the hemlock, the scene described by Plutarch mentions a religious procession conducted by horsemen passing the prison. It must have been moving along a wide street, and our ‘Piraeus Street’, on which the prison opens, was one of the principal east-west thoroughfares of the city and could easily have accommodated such a procession.

As to size and form, the Poros Building seems suitable also. There would have been no need for a huge prison because prison sentences were not given for any and every kind of offence as is done now. People were held in prison while awaiting trial or sentence, or for failure to pay a fine. Only occasionally was a prison term itself the penalty. The eight rooms on either side of the corridor probably provided enough space for ordinary needs.

Socrates was certainly a very special prisoner, and his wealthy friends were probably able to obtain certain amenities for him. When Crito arrives very early one morning, Socrates remarks, Ί am surprised that the watchman of the prison was willing to let you in’. To this Crito replies, ‘He is used to me by this time, Socrates, because I come here so often, and besides I have done something for him.’ Socrates seems to have had a cell to himself; at least we do not hear of any other prisoners sharing it, and this may have been arranged by his friends. The people who came to see him on his last day numbered perhaps twenty or so in all. These would have pretty well filled a room about 4.50 metres square. Socrates himself was fettered, so the door would be left open and visitors could come and go.

There were facilities for bathing in the prison. Shortly before the end, Socrates interrupts the conversation by saying. ‘It is about time for me to go to the bath, for I think it is better to bathe before drinking the poison, that the women may not have the trouble of bathing the corpse.’ Shortly afterwards, Socrates got up and went into another room to bathe. He spent a long time, and when he came back it was nearly sunset and he sat down, fresh from the bath. We have seen that the northwest room of the main complex of the Poros Building was arranged at about this time with simple bathing facilities, a small basin set in the floor, and a pithos to hold a supply of fresh water.

Two items found in the Annex may have some connection with its function. A group of thirteen small pots of a sort usually described as medicine pots, each about four centimetres high, was found in a context of the third century B.C., at the bottom of the cistern in the northwest room of the Annex. This is a remarkable concentration, for these thirteen little pots are a homogeneous lot and they make up about half of the total number of such pots catalogued at the Agora. There must be some reason for this concentration, and I wonder if these particular pots did not once contain hemlock, each pot holding a single dose. We know that the amount given was carefully measured because Socrates, when he was about to drink his potion, asked the man who was administering it whether he might pour a libation to some deity. ‘No,’ said the man ‘we prepare only as much as we think is enough.’ And again, when Phocion, Thudippus and others were awaiting execution in 318 B.C., Plutarch reports that ‘Thudippus on entering the prison and seeing the executioner bruising the hemlock, grew angry and bewailed his hard fate… When all the rest had drunk of the hemlock, the drug ran short, and the executioner refused to bruise another portion unless he were paid twelve drachmas, which was the price of the weight required. However, after a delay of some length, Phocion called one of his friends, and, asking if a man could not even die at Athens without paying for the privilege, bade him give the executioner his money.’

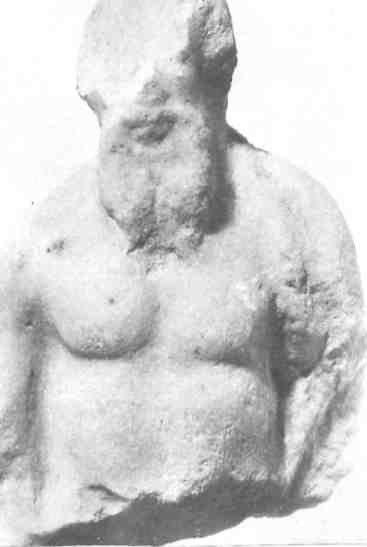

Finally we may mention a statuette of Pentelic marble, found in the northwest room of the Annex, amid debris of late Hellenistic times — the time of the destruction of the Poros Building. The statuette is broken at the waist and the preserved upper part is about ten centimetres high. The head and face are damaged at the right. We have a representation of a bearded man standing with a cloak thrown over one shoulder but leaving the chest bare. The statuette represents Socrates, and the type is best known from a statuette in the British Museum. What a statuette of Socrates was doing in the offices of the State Prison of Athens we can only guess. We may recall, however, that the Athenians soon repented of having put Socrates to death and they tried and punished his accusers. Later, a bronze statue of him was erected in the Pompeion. Perhaps one of the prison officials thought it appropriate to have a small replica of the statue in the place where Socrates was executed.

In conclusion, then, although formal proof of identification is lacking, and although the Poros Building has nothing like the dramatic dungeon of the Mamertine Prison in Rome, or even rock-cut chambers like those on the Museum Hill in Athens which have long appealed to the public imagination as the ‘Prison of Socrates’, the building does seem to meet, in a satisfactory way, the known requirements of location, form and furnishings and may be considered with some assurance to be the State Prison of ancient Athens.