I first met Christina Savalas in the summer of 1974 while vacationing in the New York area. I had heard so much about her from her children, grandchildren, and others who had known her and regarded her as a moving influence in their lives that I arrived at her home with some curiosity and anticipation. Her nature rang true to my expectations of a woman who had so firmly held on to her own identity, while raising her large, talented and dynamic family: & woman learned, patient, versatile, and proud, ready to discuss art, literature, her philosophy of life.

The poems and paintings which were Christina’s refuge and expression of her personal credo, startling for her time and place, have now received public recognition. Her canvasses, which she began to paint fifty years ago in a style reminiscent of Picasso — then in the process of radically changing the nature of art — have since been exhibited in California, Washington D.C., New York, Libya and India, and will be seen here in Athens this month. A collection of her poetry was published in Greek in New York in 1945. Thus Christina Savalas has become in her time a well-known personality, critically acclaimed as an artist, and cited as an example . of feminist emancipation. Despite these cosmopolitan attributes, her roots were simple, even humble, and make her accomplishments even more impressive and remarkable.

She was born Christina Kapsalis in Anogia, a tiny village in the Peloponnisos. Her childhood she remembers as one of simple pleasures and contentments, of family gatherings in a small room, her mother singing about a lemon tree, or the seasons, as she set the table with olives, cheese and bread — the staple food of villagers in Greece to this day. Her father was a musician who instilled within his children a love of beauty, especially the beauties of nature. (Her passionate love for her ethnic identity is such that it soon dispelled some of my own doubts, some generations younger, about the need to preserve tradition and a strong sense of one’s roots.)

Ί feel my heritage moving, boiling through my blood as I remember the words to these songs, these little poems which villagers sing when their hearts are heavy with sorrow. The olives and feta I remember more than most people I have met in my life,’ she says, alluding to those foods which represent, as those familiar with Greek ways will realize, a symbol, a security from which Greeks cannot separate themselves.

Yet she left her village behind when as a child of seven, on the eve of World War I, she immigrated with her older sister and her aunt to America, emulating so many Peloponnisians who settled in the New Land in search of a richer life. To Christina the village of her childhood remains, to this day, indelibly imprinted on her memory. Like one of her oils, it is a moment preserved, unaltered by time, a nostalgic love for her village reflected in many of her paintings and the force behind her poetry. To the young Christina, New York and America were one and the same. Anything beyond the boundaries of the village of her childhood was loneliness, emptiness. Everything was new and unfamiliar: language, food, dress, and values. Clinging to the umbilical cord of the motherland was necessary for those early immigrants to deal with the painful separation from their culture and country. Kimon Friar perceived this need when he commented that Christina Savalas’s poems are almost all lamentations, ‘… her memory of the themes and cliches of folk songs is amazing.’

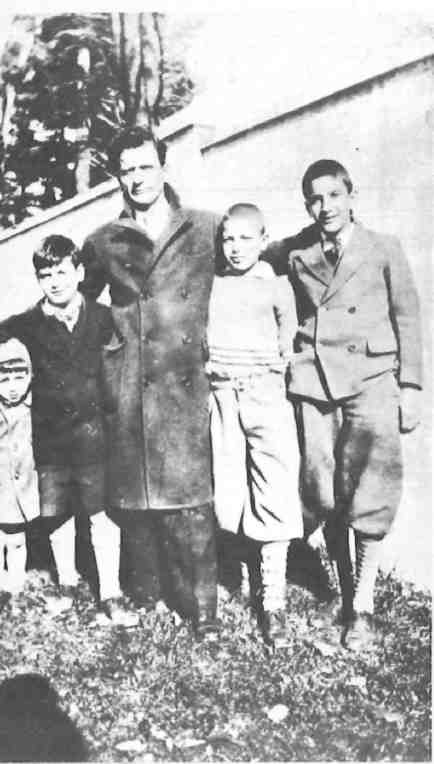

When she was fifteen, Christina married Nicholas Savalas, a clever and talented immigrant from Yeraka, a small village on the southeastern coast of the Peloponnisos; she bore him four sons and one daughter. Savalas was the perfect complement to the proud Christina, sharing her strong feelings and love for their homeland, and never interfering when she digressed from the traditional housewife’s activities. He sought to instill in his children a love of their heritage, respect for nature’s gifts, and a sense of self-worth.

Whether during times of abundance or times of hardship, Nicholas Savalas never despaired. The day after he lost a fortune in the 1929 crash, he was back on the streets of New York selling hotcakes. Mindful of the opportunities offered by America — that land of ‘mountains, oceans, trees’ — he remained proud of his background. Lining up his children, Socrates, Aristotle, Demosthenes, Praxiteles, and Katerina, and in a dramatic Savalas monologue, which his sons can be heard to echo today, he would tell them: ‘Remember your Greek heritage in everything you do. That small land, those primitive villagers, put together what the whole world copies and glorifies.’

The Greeks who settled in North America brought with them not only this unyielding pride in their homeland, but the traditions and customs of rural Greece, and the concept of family in which the mother presided over the household chores, and the men worked hard to earn a living for their family — hopefully earning enough to help support their relatives back in the villages. There was little time for other pursuits such as the arts, which were more often than not regarded as foolish and even strange. Yet long before the term ‘Women’s Lib’ was coined in the 1960s, and within the taboos of the Greek-American society of over fifty years ago, Christina Savalas discovered her own independence of spirit and thought, and chose her own course. A woman of strong personality, she rose above the limitations imposed on other women around her and began to paint and write.

Her studio was usually her kitchen where she erected her easel and worked as the food cooked on the stove and her children wandered in and out, consulting her, seeking comfort, having their scrapes and bruises attended to. During the day, and into the early hours of the morning, she painted. By the late twenties she was working in a manner which was avant-garde by any standard of that day, an unusual activity, particularly in the traditional milieu of her own community.

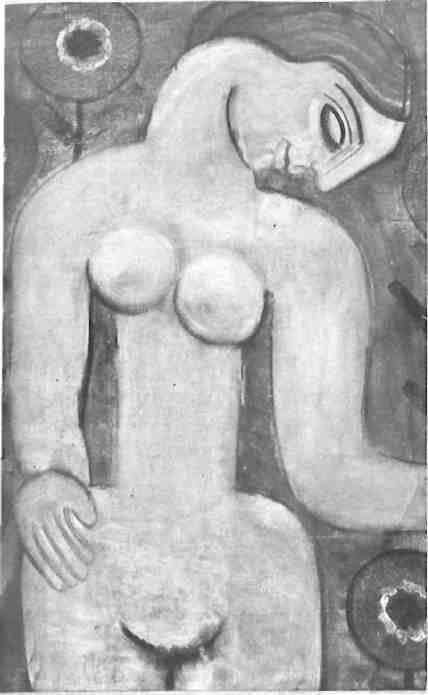

Christina painted with bold, strikingly exclamatory colours. The lines are smooth and unhesitant. Central to her canvasses are women — all-embracing, their nude physical appearances stark, but their eyes immense, dark, hopeful, yet rueful with past experience. In their hands they often hold a dove or an hour glass, symbols of hope, and of time passing, women waiting. Creation surrounds them, however — suckling infants and happy inquisitive children.

One of Christina Savalas’s favourite words is plasma, the Greek word for ‘creation’ and her paintings transmit the message of women moulding life, in quiet defiance of a society which would reduce them to passive observers. Another word which frequently enters her speech is ‘dignity’, and her women, whether sewing, sitting impassively, smiling with breast exposed for feeding, or combing their hair, possess an innate dignity and gentle power. They are clearly not the paintings of a frivolous housewife, but of a woman with a deep, confident sense of her life’s role and her identity.

Ά woman can mould the whole world,’ she said to me in a subsequent visit. ‘She was made to love and exercise her innate wisdom. She cannot kill — only if she’s insane. She cries, just because she loves. She has been repressed, not allowed to think. In some ways she has been lost, in some ways she has been beaten. But she has the power, the power to direct and make good what man has made… she is basic.’

When the Second World War broke out and three of the Savalas sons enlisted, Christina felt an even greater need to express her hopes and her fears. Until recently, she notes, war has been ‘a man’s concern’. ‘Women stayed home and prayed for good news, but the feared words could take away, at any second, what made her sit and wait, and cry.’ She began to paint and write poetry with greater zeal, her art her only weapon and solace.

It was in those years that she wrote, in the traditional fifteen-syllable line of the demotic Greek folk song: The roses heard about the dead bird and all their petals fell, all yellow-pale. And the air heard also, the trees sighed deeply, and the fresh water stream turned black. And when all the mothers who have lost a child heard about the little bird, their already scorched Hearts broke into another piece.

In her paintings more doves appeared, more women holding their children close. ‘What do men die for?’ she asks today. ‘What changes come about that seem to be good? None. Peace seems to be hiding somewhere and it is now open to women to use their innate power of leadership and love to find peace, and change the world.’

Although Christina Savalas’s paintings — as bold as her philosophical declarations and her individual approach to life — were not always understood by many of those around her, she had her mentors. One of them was the Greek sculptor, Polignatos Vagis, whose works are today included in the National Gallery’s collection, but who was then living in the United States. He encouraged her to paint and to write. The Savalas sons remember being enlisted as models for the sculptor, conjuring up a vision of a busy household with noisy and giggling children coming and going, and Vagis trying valiantly to keep his restless subjects still.

Today, Gus Savalas, standing up in his home in Athens, striking the pose of a Greek god, laughingly recounts how he and his teenaged brothers, feeling self conscious and foolish, reluctantly modeled for the sculptor as their mother reprimanded them: ‘Aren’t you ashamed of yourself! Vagis is practically dying of starvation, growing his own tomatoes, and you won’t stand still and model for him for a few hours!’ They, too, painted, he notes: ‘We loved to draw on the walls.’ Their childhood, Gus recalls, was happy and carefree. ‘We were allowed to express ourselves freely, without many restrictions.’

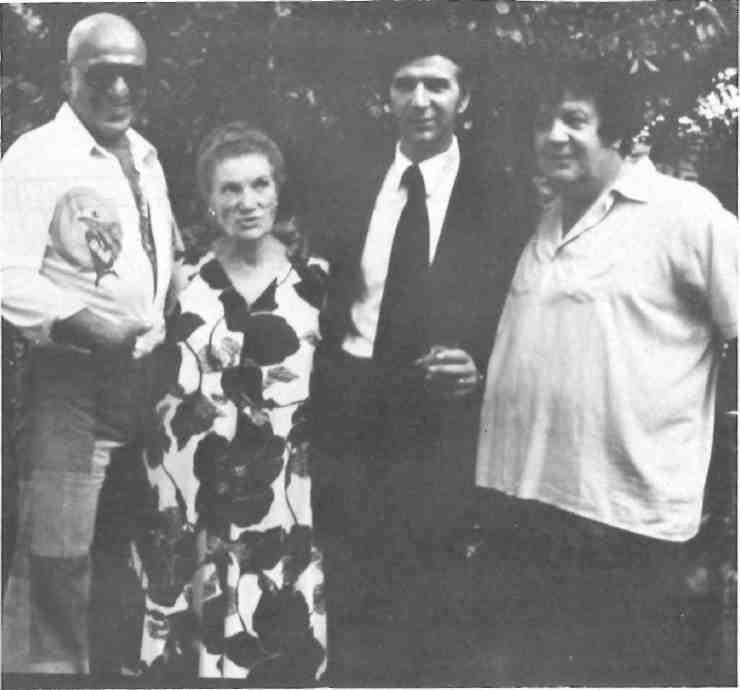

Dynamic and active at the age of seventy-one, Christina Savalas today lives alone in Long Island. Nicholas died in 1948 and her second husband, Leo Savantalios, died not long ago. She spends her time painting, writing, and keeping in close touch with her children. Her daughter, Katherine, lives in California. Socrates (Gus) is a diplomat now stationed here in Athens. Praxiteles (Ted) taught for some years in Athens but returned to New York last year. Aristotle (Telly) is on the movie-star circuit, making public appearances, giving a command performance for Queen Elizabeth a few months ago, and being very Greek on television as Kojak, where he is joined by a younger brother, Demosthenes, who plays Stavros in the series.

She still paints prolifically, but at present most of her energies are being diverted to this month’s exhibition of her works in Athens.

Although she rarely sells her paintings — ‘part of the poetry would fade from within me’ — for this exhibition Christina is making an exception and is offering three of her works for sale, the money to be donated to the Cyprus Relief Fund. Many of her paintings were lost, along with family memorabilia, in a fire at her home ten years ago. Those that remain and the ones she has since produced, most of which hang in the homes of her children, are being assembled for this spiritual homecoming. What Athenians will see is a collection of works in bright, bold colours, firmly declaring Christina Savalas’s strength and hope, her belief in woman as a benevolent, creative force.

‘If I paint a grave, I put a dove there,’ she told me last summer. ‘Again there is hope, even in the darkest hour. Death will come… but why ponder its path! Unlike the Egyptians who prepared their entire lives for the afterlife, the Greeks invented games and rejoiced in life…’

Of woman’s role she says, ‘There are more than two sides to every story, too often ignored because woman represents frailty and vulnerability. I believe woman has an understanding of life that men have refused to appreciate. Women are naturally more involved with life… they can be the source of positive action in a world full of negative responses…’