A Working Man’s Temple and Protestant Graveyard

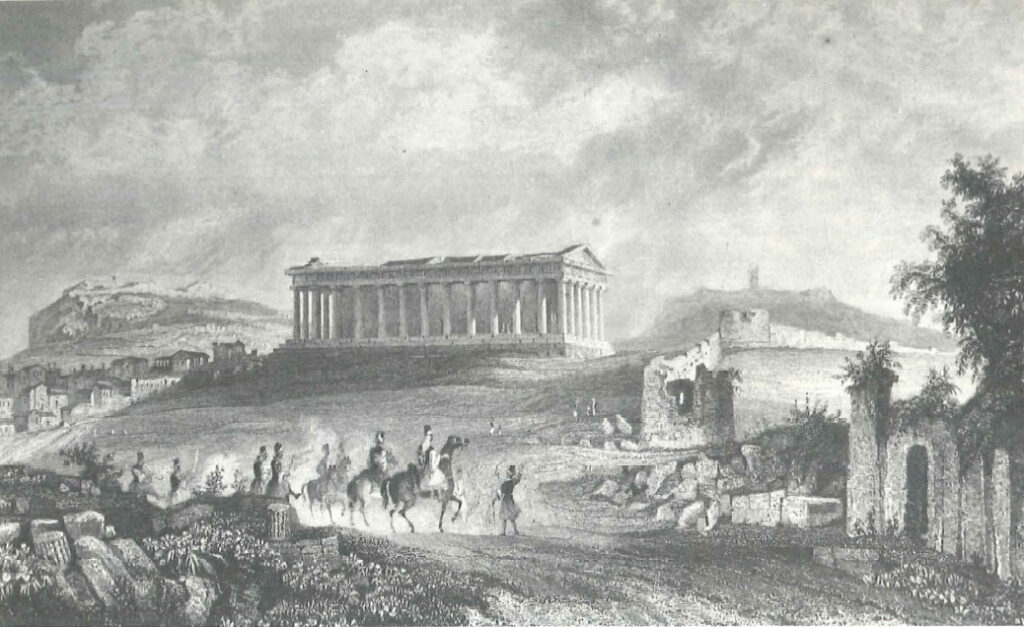

It has always been a landmark in Athens, and today gives its name to the nearby subway station: Theseion. The name Theseion is a misnomer since the temple was not dedicated to the Athenian hero Theseus but to the divinities Hephaistos and Athena. Ancient writers, however, do speak of a Theseion, or shrine of Theseus. It seems that in 475 B.C. the Athenian general and politician, Kimon, was rooting about on the island of Skyros and found some bones. Since legend had it that Theseus died on Skyros, Kimon concluded that these were the bones of the hero. He brought them back to Athens and deposited them in a shrine. Noting that the sculptured frieze above the columns on the sides of our temple illustrates exploits of Theseus, eigh-teenth century travellers drew the conclusion that the building was the shrine called the Theseion, the final resting place of the hero. Since then scholars have determined that the temple is in fact the Hephaisteion, and that the Theseion is elsewhere, as yet undiscovered or unrecognized. The old name has stuck, however, and Athenian straphangers still catch the subway at Theseion station.

The foundation of the temple was laid around the middle of the fifth century B.C., slightly earlier than the Parthenon. Construction proceeded slowly, interrupted by the war and plague that beset Athens in the second half of the century, and it was probably three decades before the work was completed. The hill on which the temple stands was a centre of industrial activity in antiquity (archaeologists have found remains of bronze foundries and pottery workshops in the area). Day labourers congregated on the hill to await employment. It was appropriate, therefore, that the new temple be dedicated to Hephaistos, the Greek equivalent of Vulcan, god of the forge, and to Athena who was, among other things, the patron goddess of arts and crafts.

The Hephaisteion (as we really should call it) miraculously escaped being destroyed by the Romans and barbarians who leveled most of Athens at one time or another between 100 B.C. and the sixth century A.D. It owes its preservation throughout the medieval period to its consecration as a church of St. George. Archaeologists excavating inside the temple found a lead box containing wax and incense under the altar, where it had been placed during the consecration ceremony centuries ago. The Christians, however, had destroyed the heads of all the sculptured figures on the temple with the exception of the Minotaur, the man-bull creature who wrestles with Theseus on a plaque or metope at the southeast corner of the building, testimony to the Byzantine bias that monsters were acceptable, heathens were not.

In the medieval period, probably from the twelfth to the fifteenth century, the Hephaisteion was used extensively as a mausoleum, and many family vaults and individual tombs were cut into the floor. The occupants of these graves were presumably Orthodox Christians, perhaps inhabitants of the local parish.

At the end of the eighteenth century the temple became the official Protestant burial ground of Athens. Englishmen had been coming to Greece for a long time before this (three of them left their autographs on the wall of the temple in 1675) but it was not until 1799 that anyone took notice of an Englishman dying here. The death of John Tweddell in July of that year put the authorities in an embarrassing position. There was an Orthodox cemetery for Orthodox and a Catholic cemetery for Catholics, but no one knew quite where to deposit a Protestant. The French consul, Fauvel, in whose arms Tweddell is said to have expired, suggested that the Hephaisteion be set aside as a Protestant cemetery.

Fauvel, however, had an ulterior motive. He was an enthusiastic dabbler in antiquities and proposed to dig the grave dead centre in the temple. There he hoped to find the bones of the hero Theseus. In this he was disappointed, of course, but Tweddell was interred in the Hephaisteion and thus a precedent was set for Protestants to come.

Tweddell’s gravestone was to become a bone of contention between Fauvel and his rival, Lord Elgin. The latter wrote a Latin epitaph and commissioned the Italian artist, Lusieri, his agent in Athens, to see to the erection of a tombstone. Lusieri no. doubt replied ‘Subito!’ — and filed the epitaph away without another thought. Elgin left for England. En route he spent three years in a French prison, probably due to the machinations of Fauvel. Meanwhile a Greek epitaph was composed and much championed by Fauvel’s friends, among them Lord Byron.

Twelve years after Tweddell’s demise, representatives of both factions met in Athens. Lusieri, his competitive spirit now stirred, began to carve a corrected version of Elgin’s Latin epitaph. The Fauvel party decided they must beat him to the punch. Locating and transporting a suitable marble slab proved difficult, however, since Lusieri had the only marble saw and cart in Athens, and he was not about to lend them out. The Fauvelites finally succeeded in placing a stone but there is no trace of it today. Meanwhile Lusieri went ahead with his Latin version as well. Fragments of that stone have been found and are now displayed to the right of the door of St. Paul’s Anglican Church on Philhellene Street. (Beside them is a copy of the epitaph of Benjamin Gott, a young Englishman who was buried in the Hephaisteion in 1818.)

Less intrigue attended the burial of George Watson, who died in Athens in 1810. Byron wrote of him, Ί knew him not, but I am told that the surgeon of Lord Sligo’s brig slew him with an improper potion and a cold bath.’ This time Byron was prevailed upon to compose a Latin epitaph. The gravestone survives, much worn, and is now built into the north wall of the temple. It reads, in translation, ‘Here lie the bones of George Watson, whom neither virtues of spirit, strength of body, the spring of youth nor this most salubrious country could preserve.’ Watson’s bones were found when the interior of the temple was excavated in 1939. It is reported in the excavation records that he had a lovely head of blond hair, and that ‘the thick sacking in which the body was wrapped retained too fully its original freshness’. His remains were decently reinterred and today still rest in the temple.

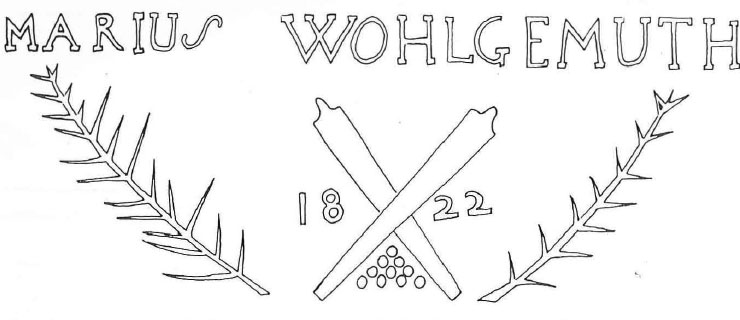

The Hephaisteion went out of use as a cemetery soon after the beginning of the War of Independence. In late April of 1822 a group of Philhellenes led a storming party against the Acropolis. One of the last epitaphs in the Hephaisteion is that of Marius Wohlgemuth, a German-Austrian, who fell in that charge. It was scratched inexpertly near the bottom of the north wall of the building. Below the name are crossed cannons, a pile of cannon balls, two laurel branches and the date 1822. The inscription illustrates poignantly the idealism and dedication that brought the early travelers and Philhellenes to Greece, some to lie forever in what one scholar has called the ‘classic and most appropriate mausoleum for those who by cruel fate expired so far from their native land’ — a corner of Greece that is ‘forever England’.