In the middle of the garden, between two waterfalls, there stood a large room, three hundred feet in diameter, whose sky-blue dome filled with golden stars, reproduced all the constellations and planets in their correct position; and this dome revolved like the heavens, driven by a mechanism as silent and invisible as that which directs the real celestial motion.

Voltaire, The Princess of Babylonia

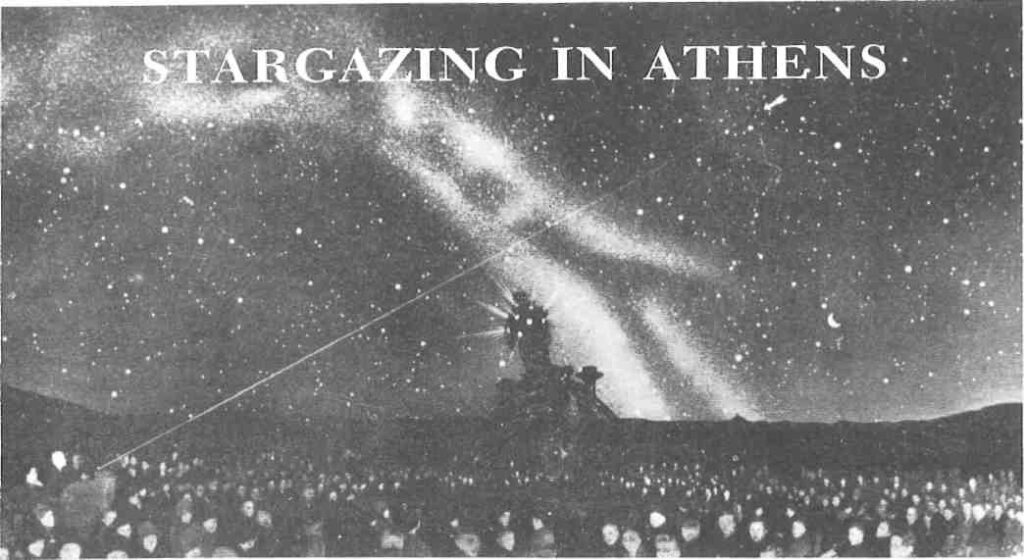

Gone are the reflections from neon signs, lighted streets, buildings and vehicles, which obtrude in large cities. Gone is the smog which clouds the atmosphere. You can pick out Orion, the Big Dipper, Sirius — or just gaze in wonder at the enormity of it all.

Forty-five minutes later you will emerge with an increased awareness of the universe, and of planet Earth’s place within the Great Scheme of Things, as well as some newly-acquired principles of astronomy.

Stargazing is not a new phenomenon. The ancient Greeks were the first to attempt to interpret the stars and to make models of the night sky. Their artists tried to portray the universe (the most familiar shows Atlas supporting the heavens) at a time when it was generally believed that the stars, planets, sun and moon revolved around the earth, which was believed to be the centre of the universe. Aristarchus, a third-century B.C. astronomer, speculated that the sun was at the centre of our planetary system, a theory revived by Copernicus in the sixteenth century A.D. A century later man was finally able to make a closer visual study of the sky when Galileo improved the telescope. Nonetheless, models made of the heavens remained small-scaled and rudimentary.

It was not until this century that a system was devised to project images of stars onto a domed ceiling, simulating the sky. Early ‘planetaria’ had observers sitting inside a large, slowly-turning sphere with holes cut out for the stars, and around 1700 the Earl of Orrery had invented a clockwork system of gears which set the planets revolving about a sun. Planetaria are no longer located in gardens as Voltaire depicted them in The Princess of Babylonia in 1768, but otherwise his description anticipated the planetarium of today made possible, finally, in 1924, by the development of a projector that is still, more than fifty years later, a mechanical and optical marvel. It took five years of research led by Walter Bauersfeld, Chief Engineer, at the Carl Zeiss Optical Works to reach this achievement. Two years later, in 1926, the projector was remodelled according to the suggestions of an associate designer, Dr. W. Villiger. This truly “Universal Projector’ remained the standard one until the 1950s when additional technical improvements were introduced.

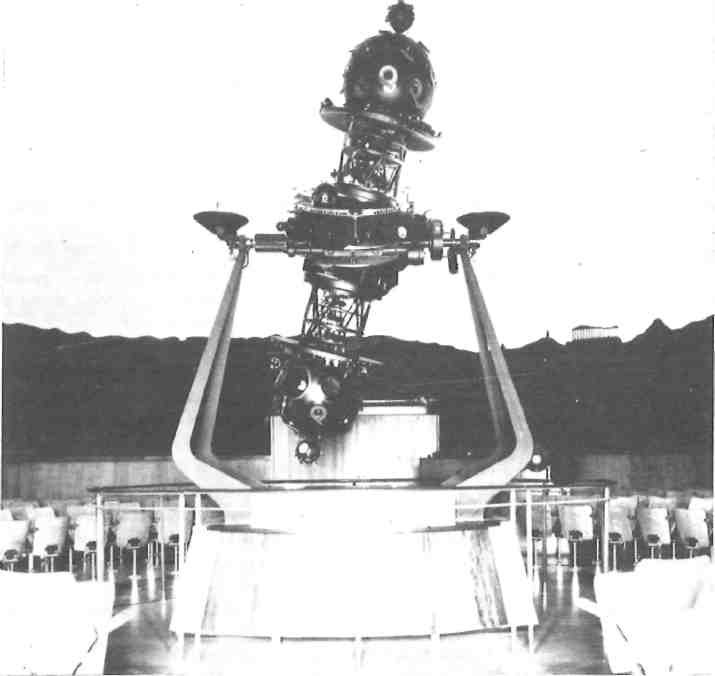

THE planetarium projector is no ordinary instrument. The Zeiss projector of the Eugenides Planetarium in Athens is made up of one hundred and fifty individual projectors which create a ‘moving’ picture of the universe, and can reproduce the sky as seen from any point on the earth at any time — past, present, or future. Five metres high and weighing approximately two and a half tons, the main projector is composed of some 29,000 individual parts. The domed chamber is fifteen metres in diameter and about ten metres high at the centre. The two hundred and fifty seats are arranged around the circular room in such a way that the viewer, gazing upwards, has the impression of being out in the open, viewing the unobstructed sky. In total darkness the technician operates quietly and smoothly and the viewer loses awareness that some earthly being is operating the controls. The equipment is so versatile that it can reproduce any aspect of the skies: constellation figures, the zodiac, eclipses of sun and moon, space probes, comets, the precession of the equinoxes, motions of the planets, sunspots, meteor showers, star clusters, nebulae, galaxies, artificial satellites, aurorae, the harvest moon phenomenon and so on. Clearly the most staggering sight of all is the view of the night sky with our own galaxy, the Milky Way, reproduced by 8,900 tiny lights streaking across the blackness, a creamy swath of stars, each a sun and many with a planetary system like ours.

Since a planetarium seeks to convey the dramatic movement within the heavens, innumerable audio-visual effects are used. In addition to the powerful Zeiss Universal projector, the Eugenides Planetarium has seventeen movie projectors, one hundred and ninety-two slide projectors which, among other things, provide one hundred and sixty panoramic scenes simulating the effects of a visit to Mars, the moon, a twenty-first century space complex, or, returning to earth, the ocean floor. The zoom powers of the instruments make the birth of the earth, or its possible extinction, astonishingly real. In fact, most people become so involved that they do not immediately realize that they are acquiring considerable scientific information within this dramatic framework.

The star performer of the planetarium show, sitting in the dimly-lit auditorium like an aberration from a science fiction film, is the projecter.

Obviously, there are various educational purposes to a planetarium. American astronauts receive their star-identification training in the planetarium at Chapel Hill, North Carolina, for instance. To the layman a planetarium demonstrates and interprets the basic laws of the universe, the nature and structure of the stars, the basic components and movements of planetary systems. To the young it introduces astronomy, a subject rarely available in elementary and secondary schools, and generally pursued at the higher levels only as a specialized science. And yet, astronomy has been introduced into our daily lives with no small amount of fanfare. From Sputnik’s first orbital flight in 1957 to the Apollo-Soyuz venture in 1975, the general public has been aware of the ‘challenge of the stars’. But astronomy remains a mystery to most and is even confused by some with astrology, the

supposed influence on human affairs of the movements of the planets and stars. There is no such thing as a typical planetarium show. Star identification is a frequent beginning, offering an early opportunity to find the Big Dipper or Taurus. As is fitting in Athens, this part of the program is accompanied by colourful tales of Greek mythology, since most of the eighty-eight constellations in the sky are related to tales of the ancient gods. This may be followed by locating Earth in the Solar System, an eclipse of the sun, views of the moon and the planets which man has probed (Mars, Jupiter, Venus, Mercury). Comets, meteorites, birth and death of a star are intermingled with moving pictures, three-hundred and sixty degree panoramas, variegated colours — all visual ‘tricks’ conceived by man and performed by machine. Tying it together are taped narrative and mood music to fit the scene. It is a total experience in sight and sound.

Usually the theme is introduced early in the program illustrating a pertinent astronomical theory or sky phenomenon. Some of the themes in the Planetarium’s repertoire are the ‘Violence in the Universe’, ‘The Birth and Death of Stars’,’Space Exploration’ and ‘Life on other Planets’, not only the possibility or probability theories within our own system, but the real, mathematical probability of intelligent life elsewhere in the Universe, and, during the Christmas season, ‘The Star of Bethlehem’. It is not surprising that astronomers should try to determine what astronomical event led the Magi to the stable in Bethlehem almost two thousand years ago. The Bible, which mentions the star four times, is quoted during the program along with historical records of the period. The most plausible scientific theory which astronomers have to offer for the nature of the star is presented, but the final decision as to ‘what the star was’ and ‘what caused it to happen’ is left to the viewer. The presentation is designed to give not only the astronomical theory but to impart the message of Christmas against a. background of traditional Christmas music.

So take a journey to where Man and Earth and our wordly concerns seem as far away as the closest star (our own sun, at that, a mere ninety-three million miles away!); where you will be struck with the wonder of the Creation and Earthman’s ability to leave his own orb to explore a minute portion of it.

It’s worth a try, don’t you think?