Stretching behind Larnaca are the great salt flats dotted with labouring men and donkeys and, further back, tightly-terraced farms with diagonally planted crops protected by even rows of cypresses. The terrain is reminiscent of the region from Jerusalem to Hebron, which is perhaps not so surprising when one remembers that for centuries Cyprus was the natural refuge for Orthodox Arab Christians fleeing periodic persecution in the Near East. It is not easy to forget that Cyprus has more than once been the scene of war, foreign domination, and refugees.

The airport at Larnaca is small, makeshift, and inadequate. As an international airport it has been in existence only a year. Cramped into what seem to be the remnants of a British Army base, it manages to have all of the basic amenities of Nicosia International, now a ruin in the so-called ‘dead zone’ between the Turkish and Greek borders. A one room cafeteria with five tables, a small lounge, gift shop, and a chaos of people are all managed by a good-natured set of officials. It has all the earmarks of the aftermath of a war. I am asked three times if I have relatives in Cyprus before I realize why I am a ‘ loner’ in the midst of transit passengers and those who are there to welcome or see off relatives. There are no tourists. I catch the mood in a large sign that dominates the exit: ‘We must all bear each other’s sufferings’.

The road to Nicosia is gained quickly. It is late in the afternoon, hot, and hazy with dust. The taxi passes through the former Turkish sector of Larnaca where new buildings are now pockmarked with bullet holes, some roofless and others with great gaping shell-torn holes in the midst of chaotically rampant gardens left untended. Strafed by the Turks in the early days of the war, it is now uninhabited for the most part.

Almost without warning or transition the road turns into the dessicated landscape of southern Cyprus. The driver says that the winter had been good-meaning that there was much rain. I wonder what it must be like here after a drought. The few herds of goats a re all prostrate from the heat ; I have never seen goats simply sitting under the blazing sun. At one turn there is a flat, grey-yellow expanse of open ground in the middle of which is a large wolf-like dog scavenging, its tail hanging limply between its legs, its shadow blue-green, an elongated stroke of jagged-edged darkness. We pass the first of many refugee camps. Mercedes, Vauxhauls, Saabs and Mini Minors are parked incongruously between rows of neat blue tents in which families have already spent one winter.

The former Turkish sector of Larnaca had reminded me of Jericho which had once been full of life and today is a desolation between Israel and Jordan. Now I cannot help but think of Jelazon, the refugee camp near Ramallab in Israel. The tents ther have long since been replaced by pise mud houses, but next to them are the empty hulls of once fashionable cars of the 1940’s, the sole remains of the means of transportation that brought innumerable families from Jaffa, Tel Aviv and Haifa. There were tents there as well before the pise houses were built. As if reading my mind the driver tells me that the Cypriot government has begun to put up low-cost housing to replace the tents.

I change the subject as it is not a happy comparison that is forcing itself on my mind. The potential possibility of political and diplomatic exploitation is obvious: who will dare to settle these refugees outside of their camps without setting a precedent that will create a defacto acceptance of the division of this unhappy island? Agencies will be created, petitions will be made. Already a ‘Cyprus Scroll ‘ signed by thousands of refugees has been sent to the United Nations. (The Palestinian Liberation Organization is already a sympathetic presence here so I am not alone in seeing the comparison.) The camps will remain as long as the problem remains. Refugees are the ultimate victims in our century. As objects of charity they lose their dignity as well as their right of self-determination. As pawns they are conveniently reduced to numbers and statistics.

WE PASS Kalohorio, once a mixed Turkish-Greek village. A mosque can be seen on one side of the road, the belfry of the village church on the other. My driver is from here and he says that the Turks left only a week before. The Greeks are still in a state of shock from the disruption as these were old neighbours and, in some odd way, old friends. No one is elated over their removal to the Turkish zone. Years before I had visited a village near Nicosia where the church and the mosque shared opposite ends of the same building. After that, how was this possible?

As we enter Nicosia we pass the Psychiatric Hospital on the left. It was bombed and strafed by the Turks, but the driver tells me that it was an understandable mistake — they thought it was still an army barracks.

I have a room booked at the Kennedy Hotel as it is close to the museum, just inside the wall of the old city. (Nicosia, like the ancient Republic of Plato and medieval Baghdad is surrounded by a concentric wall.) The hotel is oriented east-west so that from the veranda one looks out over the newer Greek side of town which is full of activity, new buildings, and well ordered traffic. From my room I can look to the north over the old city toward Kyrenia.

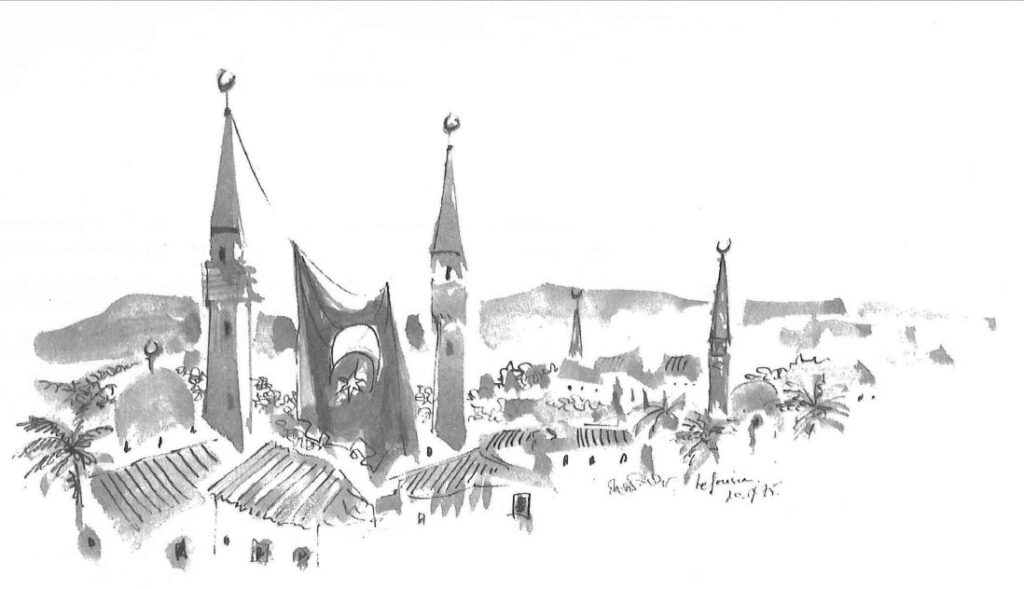

The late afternoon sun cuts obliquely across the city sharpening the contours of seven minarets and making deep shadows in the grey and deep sienna roofs. Scarlet flags are almost the only bright colour and between the two minarets of Agia Sofia hangs an enormous Turkish flag with its star and crescent clearly picked out in white. It is impossible to make out any movement whatsoever-it could be a deserted city.

At one point I can distinguish the blue cross and striped flag of Greece flying adjacent to that of Turkey; it is one of the points where the ‘green zone’ provides some sort of access between the Turkish and Greek sectors. In the late evening I take a walk to meet an old friend who has a shop in the eastern part of the city. On the way I detour in order to visit the old Venetian church that was for some four hundred years a mosque. This part of town is full of brothels whose wares display themselves on the doorsteps of old Turkish and Venetian houses. There is a large hammam with its interior wide open to view-bright carpets and hangings draped over deep divans. The area around the mosque is deserted, the minaret a silent reminder of what was once an extension of the Turkish Quarter many years ago. The windows are finely-cut, late Gothic, though it is difficult to make out where the changes in the facade have been made. A lone, grey cat watches me from the courtyard diverted only by the great numbers of sparrows that are crowding into the open windows of the mosque to nest for the night.

A. IS thinner, apparently exhausted, and obviously overworked. He has become, so he says, a realist. Once forced to leave Egypt, he has now been toying with the idea of leaving Cyprus. He has lost an old house in Famagusta and a priceless collection of Byzantine ceramics and medieval Cypriot art. His aunt is less realistic. She is undergoing her third nervous breakdown in the last year. At seventy a widow, she has lost everything: her house, a son, heirlooms, and now her health and vigour.

Some friends arrive and we go out for coffee. As I am only in Nicosia for a short time I am given the lead in the conversation which turns inevitably on the war and its aftermath. They, too, are thinking of going to Greece, Australia, or Canada. Life in Cyprus holds out only greater problems, a future that is within no one’s apparent control. It is hard to disagree. Again there is the same feeling of strange sympathy for the Turkish Cypriots, the most miserable victims of all in this whole fiasco. A’s uncle says that God is still just and that the earthquake at Lice is a sign of this. Yet again, why did it hit the poorest section of Turkey? Or is it that God is the greatest of all the Cynics, as in the story where a Cynic philosopher asked a beggar if he were really poor. The man replied, ‘Oh yes, I am poor and destitute. ‘ The Cynic raised his hand and spat on the man, ‘Then die, you poor bastard.’

The next morning I am off early to the museum. I have come ostensibly to see again the collection of Byzantine silver and a few of the icons that were in the process of being cleaned several years ago. The Director, Papagiorgiou, is away at Paphos (the mosaics, contrary to a news release, were not destroyed) so I see a sub-curator. He says everything is gone or locked away. By ‘gone ‘ he means probably lost forever-at least to the Greeks. Ironically enough the museum had opened an exhibition of Byzantine art in Kyrenia several weeks before the war broke out. The core of the exhibition was the Byzantine silver from Nicosia.The icons? They were there as well.

News has leaked out that they are stored in some sort of a warehouse and there is concern in Nicos ia that at least they are not in dampness. I am im pressed by the lack of ra ncour on the part of the curator. These are the facts of war, no more and no less. On my way back from the museum I begin to pay attention to the signs and broadsheets that are plastered everywhere.

Pictures of Makarios, demands for the withdrawal of all foreign troops, Socialist demands that Cyprus be made ‘an island of peace – not of war’, and more sadly the pictures of young men who have died in one way or another as a consequence of the July, 1974 upheaval. The Cypriots have had it finally. EOKA and ENOSIS are apparently part of a past that is not too happily remembered now, a past which bears bitter fruits. There is a hard won wisdom in the attitude of most of the Cypriots that I have met. It is the so-called Great Powers who are making the decisions. There is an atmosphere of quiet pessimism dominating thoughts about the future. The worst has, in a sense, happened.

In the late evening I meet some other friends for dinner. Three are leaving in a month for Australia, another is off to Athens. There is no mention of a return to Cyprus. At the same time we unavoidably talk about the day’s latest news of more Turks arriving from the mainland to boost the population statistics in the North. The conversation depressingly brings to my mind the exchange of Greek and Turkish populations in 1920.

I SPEND my last day in Larnaca to see the museum and a few of the old sites there. On the journey down there is silence for the most part in the taxi that I share with four others. I had not noticed before how closely the road parallels the present Turkish border. To the left, not a kilometre away, are the scarlet flags on every hill top and occasionally strung between. On the summit of one hill is a small church with a great gash of scarlet flag hanging down its belfry. We all keep looking out of th e window but nothing is said until we hit the turn-off for Larnaca and leave the flags be hind.

One of the peasant women then begins to babble in Cypriot Greek to her neighbour. It is about her daughter-in-law. Larnaca is like the bizarre setting for a play co-written by Tennessee Williams and Noel Coward. The town runs down directly onto the beach which is sandy, flat, and strung with small coffee shops-all empty. Here and the re are a few U.N. soldie rs with pale blue berets and grey shirts, blue-eyed, red-faced, and for the most part prematurely obese. An English resident lives in my hotel with his needle-eyed, unhappy wife. There are no tourists.

Toward noon I walk to the church of St. Lazarus past the Buyuk Cami, the Friday Mosque of Larnaca. A. has told me that they verified Lazarus’s bones last year, whatever that means. Are the marks of resurrection so plainly visible? Anyway, what was Lazarus doing here in Larnaca to begin with? No doubt he came in order to escape those two sisters as much as to avoid the endless questions about what it was like on the ‘other side’. The church that houses his tomb is an impressive medieval structure with anornate, squat belfry. Inside it has been stripped bare to the stone fabric emphasizing the splendid, large, newly-gilded templon. The icons are mostly eighteenth century; strangely grey-green flesh tones, large heads and splayed feet give them a stylistic unity.

There is a fine seventeenth-century icon of the resurrection of Lazarus, however, and as if to give a note of credibility to my musings on Lazarus’s fate, I see that Lazarus is shown looking decidedly embarrassed about the stench from his tomb that has caused several of the young men holding open the stone door to cover their noses. Mary, in a state of great disarray, has thrown herself simpering at the feet of Jesus, while Martha stares straight a head with clenched teeth as if saying, ‘Just wait till I get that loafer home.’

The church is surrounded by a cloister that has been given over to refugees. Through the door of the large building that was once a schoolI can make out a series of partitions made by curtains hung across wires. If each of these divides a space for a family, there are ten families living in these cramped quarters.

The adjacent Turkish Quarter has been alloted to the refugees as well. The Turks of Larnaca were some of the first to leave last year. Now their mosque, the casino, and a bank are boarded up while a good number of their houses have been taken over under government sanction. There are children everywhe. They seem as intrigued as I am by some of the old buildings. The small faces look bitter and displaced. From what I can make out the area is a developing slum — the Greeks are not proud to be living in what the Turks have left behind, and yet this is apparently all that the Greek Cypriots have left.