On our curve of the beach is only one other home, that of the Karabinis family. They are self-sufficient, living from the produce of their fields, their own chickens, ducks, pigs, and the fish caught by the brothers from their own boats. Their home is a series of connected rooms built around a central courtyard, which is bright with flowers. In many other Skyrian homes one room is set aside as a saloni, to be used only as a sitting room. In others, as at the Karabinis, it is a combination bedroom and sitting room. The decor, however, in this reception room is similar in all Skyrian homes.

At the Karabinis’, the huge double bed is pushed over into a corner. The centre of the room is occupied by a table covered by cloth of the sort that Skyrian women spend months embroidering. This is an everyday strosimata; the formal ones, called tsevres are worked with gold thread —hrisokentimata— and are used only on special occasions. The room also contains settees and a baoulo. In the baoulo — a large trunk-shaped, wooden chest — are stored the winter blankets, hand-woven with wool from the Karabinis’ sheep. On the settees are pillows or pros-kefalades, hand-embroidered with the stahi stitch, the oldest and most interesting of the many Skyrian stitches.

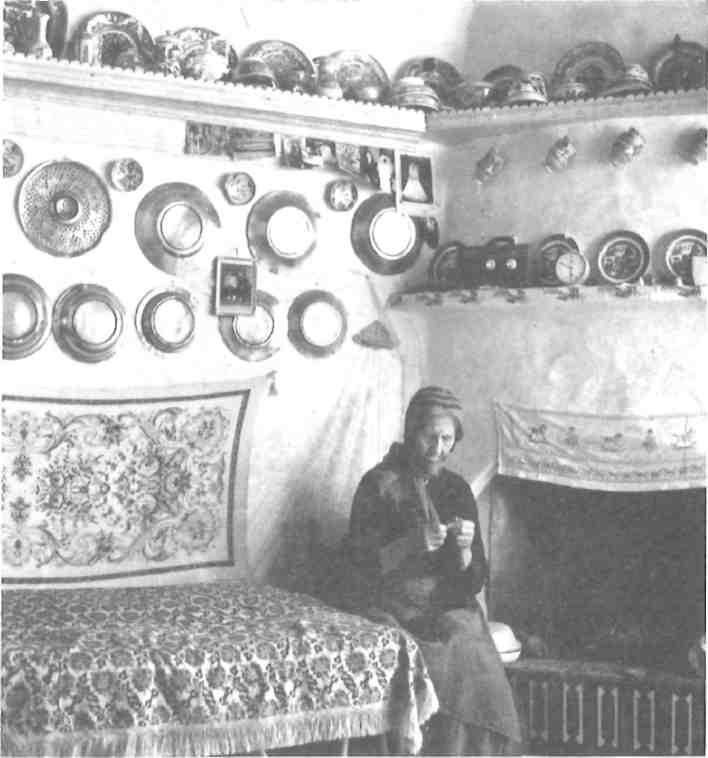

The walls of the house are whitewashed; a high shelf for the ceramic collection runs around the entire room. All Skyrian homes have collections of hand-painted plates, blue and white antique porcelain with a flower and bird design. Those who have not inherited any, or cannot afford to buy them, display instead modern plates made in England or Japan, but they are always the traditional blue and white. (The colours on the antique plates are cloudier and seem to melt into each other.) Below this shelf are hung rows of flat-bottomed copper plates, kept polished with lemon juice and sand, which belonged to Sophia Karabinis grandmother.

The saloni is the main room of every Skyrian home. There are no variations on the theme. Every home has its shining copper plates hanging on the wall, its shelf for ceramics, its embroideries, and, usually, its hand-carved furniture. On the floors are koureloudes. The name comes from koureli which means, literally, rag, and refers to hand-loomed rugs made out of scraps of old material. They are made either as long narrow runners with stripes of many colours or as chunky squares with small pieces of material attached like flaps to a sturdy base. The latter type of kourelou is the most difficult to make, confides Kyria Frosini. An old woman recently widowed, her face is smooth and unlined, her voice soft, and her manner kind and cheerful. She sits in her tiny two-roomed house with the refrigerator in the front parlour and a spotlessly clean outhouse by the front door, and chats about her work on the loom. Her five children are married now so rug making keeps her ‘busy’.

When Skyrian floors are not covered by koureloudes or goat-skin rugs, they are covered by plain, grey rugs made by Kyrios Bibis. Kyrios Bibis is also a musician who used to play with the Dora Stratou troupe. He is a curly-headed man, as sturdy as the threads he spins. He uses only natural grey or brown wool, which he places in a long bin and flails. Using stout ropes fixed to the far end of the bin, he stands at the near end, a few metres away from the foot of the bin, and slaps the ropes down with great force again and again on the wool which rises from the flailing soft and fluffy. Then, on his old metal spinning machine shaped like a wheel with little spikes attached, he draws out thick threads (sixty a day is the maximum he can produce) which he strings across his work-shop from end to end. His youngest son, the only child of the ten he sired who is still at home, works the vertical loom, weaving a rough and strong grey rug. At other times the loom is used to make the traditional grey, brown, and black striped Skyrian shepherds’ bags. Shepherds run a rope through the loops on the bag and sling it over their shoulders or attach it to their mule or donkey. Kyrios Bibis guarantees his bags for at least five years of hard use.

A VISIT to the Faltait Museum, donated by a wealthy Skyrian family, shows that Skyrian homes have not changed much since the beginning of the 19th century. The Museum preserves a whole house from that era. In addition to showing the typical saloni decor, which dates back at least a century and a half, the Museum’s house shows other similarities to today’s homes. For example, triangled into a corner of the saloni is a two-deckered, open cupboard whose recesses are stuffed with sharply-scented twigs of thyme. On these rest the traditional red and white clay water jugs (stamni) still used by all Skyrians. The Karabinis have the same kind of recess for their water jug outside the kitchen. The stamnicool the water and, because the clay has been fired, they ‘breathe’, giving the water a pure taste. Smaller versions of these water jugs, with decorative birds painted on the rim, sit on the window sills of Skyrian homes today and hold water or ouzo.

They won’t be around much longer, however. For generations only two families have made these jugs using, they say, a very old design. The younger men of these families are not interested in this craft and all but two of them have become seamen. When they die, the craft will die with them.

The Faltait Museum displays as well the old but still-current arrangement for ‘ the bedroom which juts out on a second level above the saloni; the saloni thus acquires the name apokrevato meaning below the bed. Anna Ftouli, who has a spotlessly-kept house on the Limonitria side of the village (so named for its tiny whitewashed church set in a sunken square and surrounded with lemon trees), showed me her apokrevato and the bedroom above called the sfas. In the sfas, which has a low ceiling, the family sleeps on mattresses laid on the floor. Kyria Anna, with her wide smile showing several silver teeth and her brown hair pulled back in a bun, is good company, and is quite willing to talk about Skyrian matters for hours. She has, of course, the usual copper and porcelain collections, plus a collection of antique milk-glass bottles or decanters, called firfiria, and plain glass bottles, or yapika. Most homes have a plank floor and a wood-beamed ceiling. Between the beams are lashed stalks of cane (kalamia). This is quite attractive but not very practical, as all the homeowners will tell you that the cane has to be replaced at regular intervals or it will start leaking.

Kyria Anna is working on a piece of kokinokentito — embroidery done with red silk threads. When she is finished she will wash it in tea. This bath won’t harm the silk threads, but it will give a brown stain to the background, the preferred ‘old’ look.

Only a few things have passed out of common use on Skyros; certain implements, for example, which are exhibited at the museum in the storage room. These include the clay pots used to smoke bees out of their hives before the honey was collected. The pots, which were carried along by a handle, were perforated so that the smoke could escape. The honey was stored in plaited wood containers as high as a man’s waist and plastered with cow dung, a treatment guaranteed to keep out cold, heat and air. Hanging on the wall of the storage room are flat wooden circles about three feet in diameter with what looks like large upturned egg-cups for bases. These low tables, around which families used to sit cross-legged and eat, do not exist on the island any more, except as antiques.

The dress of the Skyrians is unique. All women over thirty, except those in mourning, wear the Skyrian headscarf which has a black design on a yellow ground. It has been a part of their everyday attire for well over a century. The Faltait Museum shows the same scarves worn by women of 150 years ago. The few tourist shops on the narrow cobblestoned street that winds through the centre of the village also carry these scarves and sell an occasional one to foreign visitors, but the Skyrians all shop at Kyrios Lefteris whose store is found in one of the narrow, almost claustrophobia-inducing back streets. There are two types of scarves: regular weave for daily use and fine weave for Sundays. Special orders of these scarves are turned out by the same factory on mainland Greece that makes scarves for the whole country — but the yellow and black ones are for Skyros only.

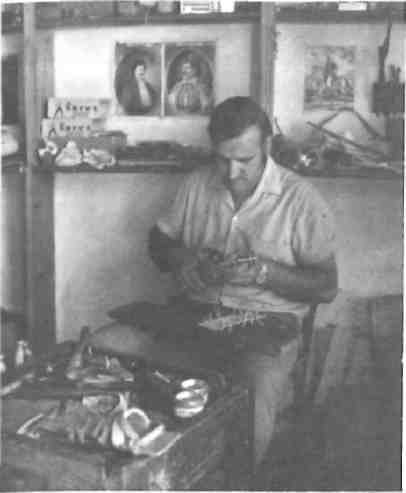

The older men of the island wear the Vraka, a kind of baggy trousers; a collarless long-sleeved shirt made of homespun and finely checked in black and white; a black scarf wrapped around their heads in lieu of a hat; and trohadia for shoes, sandals made of leather strips, whose name is also unique to Skyros. Kyrios Karabinis is the only cobbler who makes them. (Most of the islanders share a few surnames and this Kyrios Karabinis is only a distant relative of the Karabinis of Kalamitsa). The name trohadia applied to these scandals of wrapped strips of leather is derived from the verb treho, to run. The trohadia worn by farmers and shepherds, who are out in the hills and fields all year, are made with soles of old tires; otherwise the sole is leather. To make these shoes Kyrios Karabinis measures the foot, cuts out a base — a flat oblong of virgin cowhide on which the strips are woven through slots cut in the sole to make the shoes. No nails or glue are used.

Kyrios Karabinis also makes kountoures or bridal slippers. All Skyrian women are married in the traditional bridal outfit — which one can see displayed in the Faltait Museum — a heavy garment, clasped by a belt of wide metal and bearing a strip of white fur down the front. These dresses are not being made any more, as they are too costly, but brides use those in their family or borrow old ones from neighbours rather than be married in white. For their slippers they bring a piece of brocade to Kyrios Karabinis and he makes a mule with dainty pointed toes, edged in strips of silver leather.

THE Faltait name lives on in Skyros. One descendent, Kyrios Yorgos, is very interested in preserving the ancient Skyrian designs which he diligently searches out and reproduces on pottery plates, or hand tools on copper plaques (the latter a kind of ‘old wine in new skins’ concept).

Kyrios Yorgos loves to talk about his craft. He decided on his profession after viewing with disgust the travesties of Skyrian designs in Athenian shops. These, he says, are perverted, are no longer genuine, and show no regard for authenticity. He has resurrected the originals: theGorgons,the Tsalapetinos (hoopoe), the Kadis-Singer (a design from the Turkish occupation when the ‘Kadis’ served as judge), the Ship, the Marriage, the Bagasaki (a dancer costumed for the First of May), the Two-Headed Serpents (Fidia), and the Byzantine Double-Headed Eagle. Gaily-plumaged and crested tsalapetini are still found on the island; they are fortunately small birds and not hunted, as Skyros has an abundance of perdika — partridge — and wild hares. The tsalapetinos design is used alone or in combination with a pomegranate, which stands for happiness and productivity and is thus a suitable symbol for large families and good harvests. Kyrios Yorgos is pleased to see that in the past ten years interest in the embroidering of these old designs has been reviving among the island women. Embroidery is the oldest form of Skyrian art, much older than the wood carving for which the island is famous, but the. wood carvers, too, preserve the ancient designs.

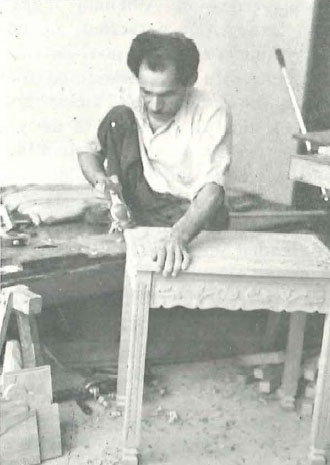

Skyrian wood carving is a craft always learned from the father, who learned it from his father, who learned it from… and so on. The carvers use either the dark wood of the walnut, or karydia, or the light wood of the beech, or oxia. The wood is imported, usually from Rumania, as Greek wood is not of good quality and splinters easily. Carving is time-consuming and requires much patience: twelve hours are needed to turn out a straight-backed chair, a week for a small chest, two weeks for a large chest. This chronology was given to me by Emmanuel Manolios, a carver who works in a shop filled with rows of canary cages; the twittering of the birds accompanies his work.

Kyrios Manolios says that finding dark wood nowadays is almost impossible and carvers must resort to staining for those customers who prefer the dark effect. Stamatis Babousis has a stock though, and explains that the dark wood is better because it grows darker and more lustrous with age. Kyrios Babousis is the master carver of Skyros; he takes fifteen minutes to prepare one side of a short chair leg. The wood is scooped out in tiny petal shapes with a metal scraper. He is working on a chair back with a design of two birds, what he terms a ‘Helleno-Byzantine’ design, and shows me how even the background calls for painstaking care. The background creates a plekta (knitted) effect, being covered with minute indentations created by hundreds of light taps with a hammer onto a flat-headed, blunt instrument that incises the lines.

Another facet of the wood-carving is revealed by Yannis Aggelis. He shows me how the patterns he uses are taken from antique chairs in order to recreate authentic old designs. He puts a piece of oiled paper over the pattern and then, with a carbon sheet, rubs over it. After several rubs the pattern is transferred to the paper. The paper is reversed, and with the carbon placed underneath he traces, with a pencil, the design onto a new piece of wood. Kyrios Yannis Aggelis has been cruelly crippled from birth, but his hands are deft and sure. He makes modern reproductions of old chairs and also beautiful baskets out of strips of reed and strips from the Aligaria shrub, which blooms beside all Skyrian roads. These baskets are works of art. First he cleans and trims the wood, then he makes a framework shaped like a caique out of the Aligaria wood on to which the reeds are woven. The actual weaving is a job that, depending on the size of the basket, may take all day. Ragged edges on the sides are trimmed off; at the top they are turned under in a scallop effect.

THE women of Skyros embroider in the evenings when the day’s work is done. Most of their work is used in the home; an abundance of embroidered pieces is considered necessary for the typical saloni. The women use silk threads coloured with natural dyes, and work on pieces of fine linen, either ransacking their grandmothers’ chests to find a piece of old material or else making a new piece look old by soaking it in tea, as Kyria Anna was doing, or in a brew made with onion skins. They draw the design on the fabric and then fill it in with a variety of stitches, which they call generally arhaia velonia (ancient stitches). These stitches can actually be divided into two main categories, the grafta which are embroidered on a frame, and xompliasta which are not. Numerous types of stitches form sub-divisions under these two main categories. The stahi is the oldest of all, dating back to Byzantine times. Expert embroidery in the stahi stitch looks the same on both sides of the fabric.

Skyrian designs are unique. In contrast to the geometric patterns of much Greek embroidery, here we have figures — people who play out their roles on any typical piece of embroidery — and Skyrian embroidery is further distinguished by its sense of fantasy. It is fascinating to explore the sources of all these designs. Many have been taken from century-old kerameika (pottery) or engraved copperware brought long ago to the island by pirates; they have never been derived from woodcarvings. Others have come from either the East or West as each played its part in the history of the island. For example, a whole set of Frankish characters, particularly mounted horsemen, remind one of the Frankish period in Greece. Another set of characters remind one of the Turkish period, the main motif here being named after the Kadis who, as the main representative of the Turks, served as judge for the island, and sometimes governed. Apart from the characters of historic significance, the embroidery also shows monsters, half-man half-beast, such as gorgons; real or fantastic animals; an abundance of birds; and ships — karavia. The latter are perhaps surprising if we consider that the people of the island have never been noted seafarers. Experts speculate that the elaborate minute details on most of these karavia must be derived, not from real ships, but from folk paintings of ships. Then there are the flower and plant designs, the most popular being the glastra — plant, usually fantastic, growing out of a pot. All island women, even those well into their eighties, embroider. It was not always so, as embroidery used to be the jealously guarded pastime of only the wealthy. It was not popularized until 1915-20, when embroidery became a part of the school curriculum for girls. At the same time, and because of the unwillingness of the wealthy to let their treasured designs be embroidered by the poorer classes, the school teachers introduced the red embroidery — kokinokentito — now often associated exclusively with Skyros. Its exact origin is unknown, however, and it is attributed to various parts of Greece. There is an old proverb that says of the women’s handicrafts on Skyros ‘Embroidery is fun; weaving is slavish’. The island women do both, of course, but their main love is embroidery, and so they sit (all of our many friends there, Kyria Nitsa, Kyria Frosso, Kyria Anna) plying their busy fingers and at the same time socializing and sharing patterns with each other, while the men carve the furniture in traditional patterns or make pottery and baskets. Thus the folk arts of Skyros live on — the past inspiring the present.