Gaily decorated stalls and booths will sell inexpensive icons and prints of St. Marina, the traditional votive offerings or tamata, various kinds of phylacteries, small bottles of holy water and oil, and a large assortment of candles of all sizes. Children clothed in black will accompany their mothers to the shrine for vespers. There the children’s clothes will be removed and placed on a pile next to the miraculous icon of the patron saint. The children will be re-dressed in new, brightly-coloured garments brought along for this purpose. Although large numbers of women and children attend this panigiri, devotion to the saint is certainly not limited to this annual occasion. Throughout the year mothers, children and young married women visit the church.

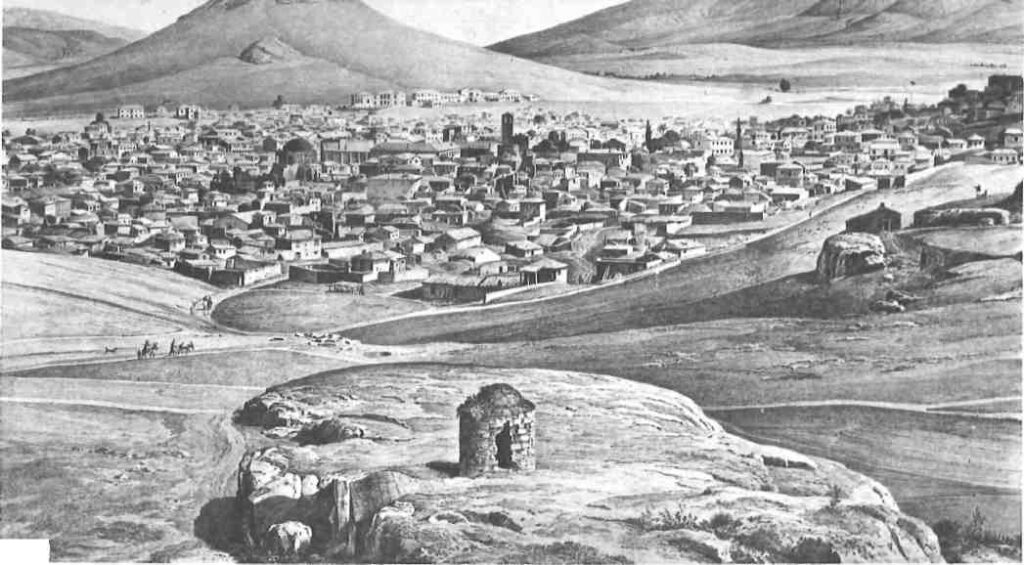

PERHAPS only a few elderly people living around the Theseion district of Athens still remember how in the past women used to slide down the polished marble slab on the slopes of the historic Hill of the Nymphs. About fifty years ago the smooth, inclined rock, polished by generations of sliding women in search of a cure for barrenness, was destroyed when the Church of St. Marina was enlarged. Today the sliding is forgotten and mothers and children, the barren and the sick, call upon St. Marina for favours.

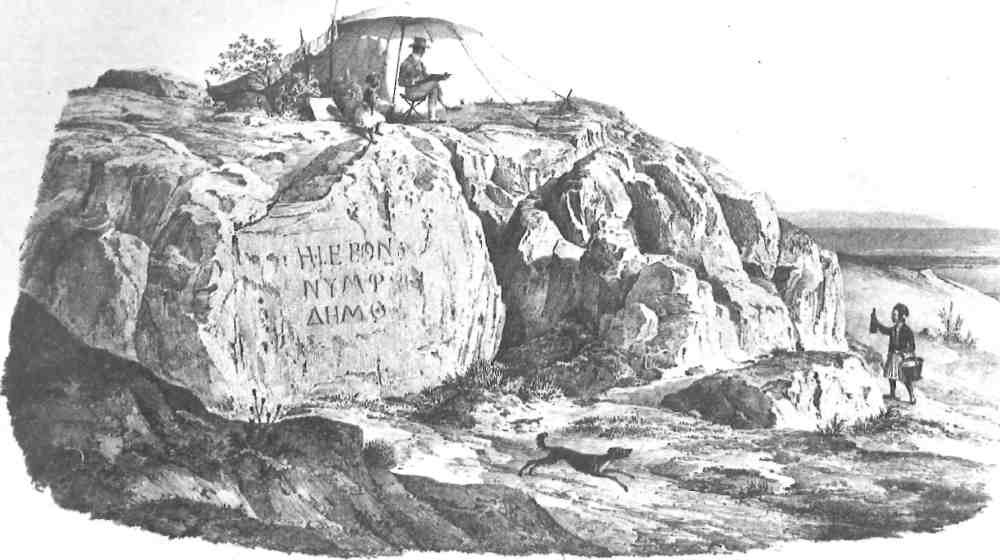

The hill received its name from a fifth century B.C. dedicatory inscription to the Nymphs carved on a rock now inside the garden of the Observatory. Which of the Nymphs were venerated on this hill is not known. It has been suggested that they were the Hyakinthides, the daughters of Erechtheos, who cared for the infant Zeus. In general, the Nymphs were divinities, marriageable women of inferior rank. Any cult associated with them would naturally be related to fertility and health. They were also regarded as protectors of children.

The slopes of the Hill of the Nymphs are covered with ancient foundations in the midst of which stands the Church of St. Marina, near the site of a former sanctuary. Traces of medieval wall-paintings in the cave-church testify to its antiquity, and according to E. P. Blegen, the Grotto of St. Marina was already a Christian church in the Justinian Era. It has been suggested by several scholars that the devotion and piety expressed by women at the Church of St. Marina have pre-Christian antecedents. Unfortunately there is no literary evidence, except for the inscription, of an ancient fertility cult on this particular hill. The earliest literary evidence comes from the pens of nineteenth century travellers to Athens.

Climbing the Hill of the Nymphs and sliding down a smooth rock was a widely accepted practice among two categories of women: the barren who wished to become pregnant, and the pregnant ones who wished to have an easy labour J.L.S. Bartholdy in 1803 mentioned that women cursed with sterility indulged in this activity. Three years later Edward Dodwell elaborated on the custom when he wrote that ‘not far from the kaki pethera, or the Old Hag, there is a rock a few feet in height, on which newly married women sit and slip down, in order that they may be blessed with a numerous progeny of males. This rock is so much in fashion that its surface has taken on a beautiful polish’.

Around 1820 F.C.H.L. Pouqueville, the French Consul General to the Pasha of Yiannina, added that in the act of sliding these women invoked the Fates and the Fairies by saying: ‘Have me fated too, You Fates of the Fates’! The nineteenth century Greek ethnologist, K.S. Pittakis, and Lord Denison both believed that the custom derived from an ancient cult in which, after sacrificing to Diana, under her attributes of Lucina, the women would bathe in a hollow scooped out of the rock and then slide down the smooth side of the rock from a height of several feet. Bayard Taylor in 1858 added that pregnant women would perform the same ceremony in order to ascertain the sex of an unborn child. The inclination of the body to the right or the left indicated whether they would give birth to a boy or a girl. In his learned dissertation written in Latin, Athenae Christianae, August Mommsen stated: ‘At the church fifty marriageable girls were also present. They go there preferably on the seventeenth day of July on which day takes place the celebrated fair of St. Marina’. By the latter part of the nineteenth century, the practice had significantly declined ‘on account of the hesitation or shame in view of the many Franks (foreigners) in Athens’.

If there had been a pre-Christian healing cult on the Hill of the Nymphs, its transfer to a saint like St. Marina would be understandable provided that we identify her with the woman-monk St. Marina, rather than with the better known St. Marina of Antioch. Possibly a confusion of identity arose concerning these two at an early date.

The Greek Orthodox Church in general, and the Church of St. Marina in particular, venerate the third century Antiochene virgin-martyr, Marina, who killed a devil by making the sign of the cross. It is she who is commemorated on July 17 and icons portraying her killing the devil are widely displayed. The relics of St. Marina the Great Martyr are found in numerous places. Her skull is believed to repose in the Monastery of St. George in Edipsos on Evia, while a section of one arm, parts of her left hand and all of her right are said to be scattered in four different monasteries on Mount Athos. The Monastery of St. Stephen at Meteora claims her foot and some of her hair is venerated in the Church of the Nativity of the Holy Virgin in Korfietissa on the island of Milos. Still other parts are found in churches and monasteries on the mainland and islands. There is, however, nothing in her story to suggest any concern for either the sick or for children.

On the other hand, a woman-monk, Marina, is venerated by some of the Oriental Orthodox churches on August 21. The daughter of wealthy Christian parents, Marina wished to enter the ascetic life. She assumed male attire and joined a monastery where she became known as ‘Marinus’. On one occasion ‘Marinus’ was sent out on business and had to spend a night in an inn where a soldier also lodged. During the night the soldier slept with the innkeeper’s daughter, but advised her to lay the blame on ‘Marinus’. The innkeeper complained to the abbot who expelled ‘Marinus’ from the monastery. The innkeeper’s daughter gave birth to a son; ‘Marinus’ cared for the infant, setting an example of piety, and the child in her charge was reared in devotion and asceticism. At length ‘Marinus’ died. As her body was placed into the grave, the secret of her sex was discovered and her innocence proved.

Although nowadays this tradition is generally unknown in Greece, there seems good reason to believe that it initially provided a Christian patron for an already existing cult centre and that the woman-monk, Marina, later became identified with the Antiochene virgin-martyr.