By no means was this our first hint of extraordinary happenings on the Agion Oros, the Holy Mountain. Days before in Karyes, which serves as administrative centre for this independent colony, we had read a neatly framed announcement which said:

Dear Sir: You doubtless realize that you are now travelling towards a Monastic State, ‘The Garden of the Virgin Mary’, far from the secular world, a State where prayer, the constant praise of God, the purifications of the soul and spiritual asceticism are the main pursuits of life… we can thus repeat that ‘this land is subject to miracles’.

Earlier that same day, a soft-eyed monk had leaned across the aisle of our crowded, struggling bus and advised us to greet the icon of the Panagia Portaitissa (The Virgin of the Gate) at Iviron so that the Virgin might assist us during our stay. My intention was to comply, out of respect if not out of faith, as I caught my first glimpse of the monastery’s perch above the shore. Panagia is the Blessed Virgin Mary.

One day before reaching the peninsula of Mount Athos, we had come to the small village of Erissos. Inevitably, perhaps, the romantic temptation arises to view it as a final way station, this side of some dark, alluring unknown. I resisted this feeling until evening when two old fellows in the kafenion enthusiastically sketched the history of a golden icon which had floated from Constantinople to Mount Athos hundreds of years before — the icon of Panagia Portaitissa. That, then, was the first talk of miracles, when we were still able to classify it neatly as imaginative, harmless legend.

Setting out slightly before six o’clock each morning, the bus from Erissos proceeds towards the Gulf of Agion Oros in darkness. Its journey is brief, crossing a slender isthmus that joins Mount Athos to the greater peninsula of Halkidiki below Thessaloniki. The bus passes the ancient site of the canal cut by Xerxes, descends to the shore at Trypiti, and stops in front of a short, simple pier. From there a chugging caique extends the voyage, depositing some travellers, and all females, at Ouranoupolis before continuing on to Daphni, the point of debarkation into the richly forested world’of spiritual stone fortresses.

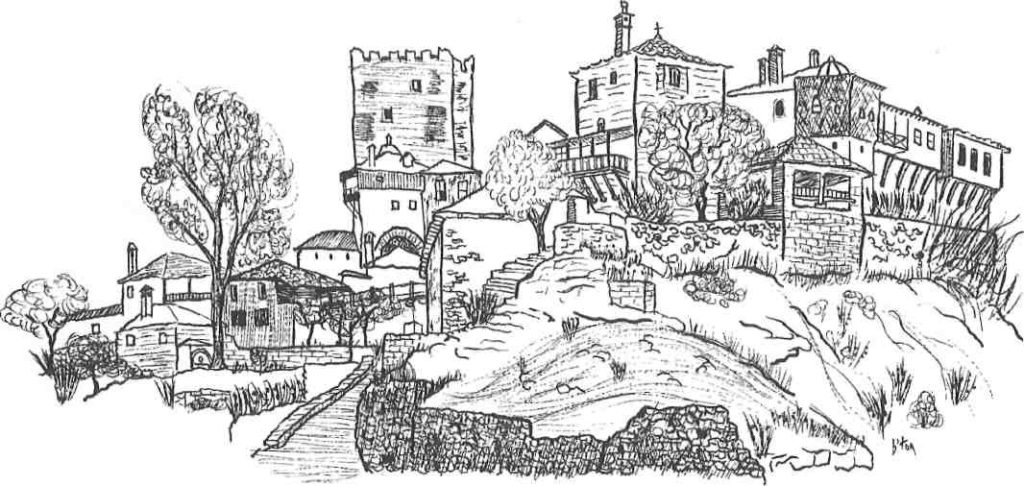

Actually, much more than a fortress surrounded us at each of three monasteries that hosted us prior to Good Friday. Had I not known where I was on approaching Vatopedi for our first night’s rest, I might have guessed it to be a factory, chateau or castle. Robert Byron notes, in a windy book about Athos, that it ‘…has achieved the impregnation of the utilitarian… with a sense of something other than the present’. At such large, sprawling, monastic sites as Vatopedi and Great Lavra, this impression appears to result, primarily, from an eclectic piling-on of architectural flourishes over the decades. Thus a visitor may poke around through absolutely distinctive courtyards amidst a myriad of colours, building materials, arches, balconies, and staircases.

There are two types of monasteries on Athos, the idiorrhythmic and the cenobitic, representing two life styles officially defined by the Synod at Karyes. The first implies that each monk may prepare his own food and rely on private resources. An outward sign of this is to be found in the abundant sprouting of chimneys at Vatopedi. At Pantokrator, an eccentric and jolly cook shuffles between balconies in his withered grey habit, mothering guests and fellow monks alike. A fondness for Pantokrator is largely engendered by human personalities, whose frailty may speak well for the cenobitic orders.

The Greek root of cenobitic means ‘communal life’, and its full implication is established by the procedure which is followed during meals at the meticulous monastery of Stavronikita. Having succumbed to the lure of a sundrenched Aegean, we arrived, after a swim, late and wet, at the refectory door. Sheepishly filling a vacancy at the near end of a long wooden table, I admired the sparse, attractive setting placed before me: a low-brimmed, wide, metal bowl filled with thick bean broth, a glass of dark wine, and a slice of black bread. Running down the centre of the table was an arrangement of bread baskets, dishes of halva, and hammered metal pitchers. Silence prevailed throughout the meal in deference to a monk reading the scripture from an adjacent rostrum. Sunlight from a large window at the far end of the room silhouetted the aged abbot seated at the head of the table and created a brown translucence through the long beards of the monks’ lowered heads. Soup was consumed methodically and efficiently. A drone of lips and silver provided a basso continuo for the single hurried voice.

As my companion remarked, Stavronikita in its impersonality will likely remain unaltered by the passage of time. Perhaps such must be the goal of a purely ascetic order. As long beards and black habits suggest, all inhabitants are to look alike and to act in unison. Exactly who is upholding the submission before God is of limited importance provided that this human condition, this penance, is upheld.

Mindful of the advice given by our old friend with the bushy, white moustache, we entered the fat, wooden gates of Iviron, which are completely covered by horizontal bands of metal. We still had hours of Good Friday daylight to spare. Immediately, a garrulous visitor befriended us and volunteered a tour of the environs. His ensuing monologue filled in every detail concerning the Panagia of Iviron. We were shown the icon, told tales of.its long life, and led to the spot where it was fetched from the sea.

Throughout the afternoon another visitor, a gaunt old man, trailed behind us. Periodically he would punctuate the other’s tales with a somber interjection, nodding his head slowly, jutting forth his lower lip, describing small clockwise circles in the air with his right hand. ‘Vevea… thavma,’ he would say, ‘No doubt… a miracle.’

The expert juxtaposition of colours and the refinement of facial expression achieved in Byzantine art are evidenced by chapel frescoes throughout the Athos peninsula. Unfortunately, icons such as the Panagia Portaitissa serve more as testaments to extravagance. Three distinct layers of gold craftman-ship surround the faded faces of Virgin and Child which are the only visible areas of the original painted surface. Each face is roofed by a projecting, luxuriously – jewelled crown. Displayed within the glass-fronted casing is an assortment of watches and rings left in tribute by previous visitors.

Such a lavishing of gifts before the altar of the Protectoress may be meant to have a sedative effect on her periodic wanderings. Upon arriving within sight of the shore at Iviron, the icon allegedly withdrew at the approach of boats from the monastery. It was finally retrieved by the ascetic Gabriel who, instructed in a dream to walk across the waves, found the Panagia radiantly upright beneath a column of light. More than once, under cover of night, the icon has miraculously transported itself from inside the monastery to a station outside the main gate, reminding perplexed monks the following morning: Ί am here to guard you; you need not guard me’. Accordingly the monks of Athos hold that on the day the Panagia Portaitissa takes her final leave, catastrophe will envelop the entire peninsula.

As promised, the Miracle of the Kandili occured during the Good Friday vigil. The nave of Iviron’s church was majestically lit by the reflection of worshippers’ candles off the lavish gold and silver decor. Older monks and visitors rested against the high wooden seats, or stassidia, and followed the rhythmic chant of the passion story, led by three groups surrounding the flower-laden bier of Christ. Incense and sweet waters scented the air. The abbot and elders appeared in beautifully embroidered robes while their underlings floated in and out of the darkness dressed in the customary black.

Suspended from the iconostasis (altar screen) was a row of thirteen kandili, holy lamps, each held by three thin chains that came together at the top where they were attached to horizontally projecting brackets. Shortly after midnight the central and largest kandili began to sway in an arc of about forty-five degrees. It continued this performance for the remainder of the service, eliciting a peaceful smile of satisfaction from one elder as he raised his eyes. Each year the kandiWs movement signals good fortune, provided it limits itself to a simple arc. In 1940, it reportedly whirled violently in circles and crashed to the ground, a harbinger of the Italian invasion. My companion and I left the church with wide eyes, theorizing quietly about the sympathetic vibration of sound-waves.

The morning of our last full day on Athos was pure sunlight, and the lichen-covered roofs at the Lavra monastery shone richer than any golden treasures. After a boat ride up the northern shore, we were served a hearty meal of lamb, bread, and wine, much appreciated after the bean broths of Lent, by an elderly Iviron monk. As we ate, he explained his relationship to God over the past forty years which he had spent on Mount Athos as that of student to teacher. ‘If you are attentive from day to day, the teacher will help you in times of need.’ Asked about his commitment to the secular world he said, ‘We wear black to express our sorrow over the condition of all men, and hope that visitors absorb not only the beauty of Athos but also a desire to tell others that we monks are setting a worthy and good example.’

Any careful observer will certainly sense a religion which inspires awe, with multi-headed monsters set to devour the faithless. However, the opportunity to live a week on Athos also reveals the human charms and failings that mark any community of people. Beside the small harbour at Vatopedi, workmen saw lumber from the forests and prepare it for shipment to Kavalla. A sign, written in Greek on one side, carries this slightly ambiguous translation on the other: Forests are Gods Miracles. Take Care to be saved from fires. ‘I’ll try,’ I thought upon reading it, ‘but I’m not promising anything.’

Five minutes by boat north of Daphni stands Panteleimon, home of a Russian order that is slowly dying for lack of new blood. A visitor takes his meals in a huge refectory, able to accommodate 1500 persons below the expanse of frescoes that adorn its spacious ceiling. Now five, perhaps ten, monks, ranging in age from sixty to ninety, scatter themselves here and there at the long, otherwise vacant tables and doggedly perpetuate their monastic traditions.

Kyrieleison, kyrieleison, kyrieleison… fires out an old voice as the dinner concludes. ONE two three four ONE two three four ONE two ONE two ONE two three four sounds the rhythmic mallet against the drum-like slab of wood, calling monks to prayer, as the morning caique churns away towards Ouranoupolis.

Note; Letters of introduction to visit Mount Athos may he obtained from the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, 2 Zalokosta Street, upon presentation of a letter from one’s Embassy. The letter is easily obtained. Room and board are free at the monasteries on the peninsula and visitors are customarily granted one-week passes.