Once beyond the exterior, however, one’s impression changes dramatically. The lively, chaotic buzz of Greek and English in accents often carrying echoes of England, Australia, the U.S.A. or you-name-it, can be heard in and out of the classrooms. Lockers, posters, bulletin boards line the corridors. Classrooms alternate with offices in a seemingly schizophrenic floor plan.

There is no cafeteria perse and on a sunny day, students settle themselves outside on anything flat. Visitors attempting to cross the Outdoor cafeteria’ zone during lunch hour must navigate a course between hamburger and sandwich-eating students and a variety of impromptu ball games: English football (soccer), American football, baseball, basketball (or ‘basket’ as some of them call it, in Greek fashion). Other students may be spotted sitting beneath a tree poring over their Greek readers under the guidance of a native-speaking instructor. Or a German or French or Spanish reader, for that matter.

The frequent visitors on campus sometimes even include the police. On the road that separates the two halves of the campus, a police car draws up, two horofilakes climb out and enter the business office, while the uninitiated ‘ speculate about what they are doing there. They emerge a few minutes later carrying stacks of paper. They have come to use the school’s mimeograph machine.

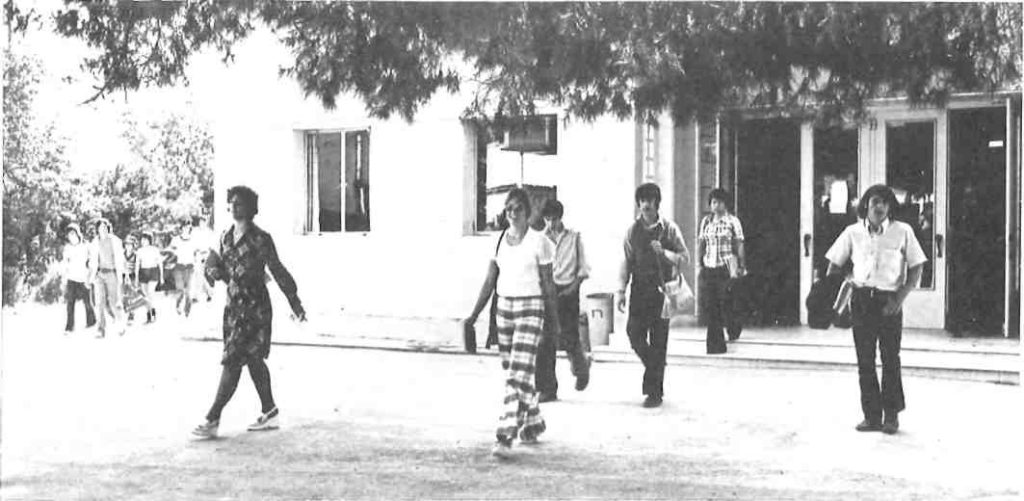

The faces, the dress, the shouting, the giggling of the assembled knots of students might be those found at any number of schools, but this is the American Community Schools of Athens and the similarity is only surface. The name is something of a misnomer unless one thinks of ‘American’ in the broad sense, as a society composed of many ethnic groups.

A member of the faculty with an Anglo-Saxon sounding name may be from New Jersey, Cairo or Germany and refer to his or her ‘village’ in the Peloponnisos. A call to the home of an ‘American’ faculty member may be answered by a Greek husband, a Greek mother-in-law, or an ‘American’ mother who, after many years in America, is still more comfortable in her native Greek. These are probably the more permanent members of the faculty. Others are here for a brief sojourn to add another chapter to their curriculum vitae: the experience of teaching abroad. In return, they bring fresh ideas and stimulation.

The American Community Schools of Athens are something of a paradox. Their ‘image’, as all will agree, is unfortunately misleading. Placed in the middle of Athens where children — even boys in the lower schools — traditionally wear smocks to attend classes, the liberal dress of the students of A.C.S. is startling. This factor, perhaps more than any other, accounts for the unjustified reputation it has in certain circles (belied by the results and the facts).

ONE OF the most outstanding features of A.C.S. is the faculty. They must meet the standards set by the most rigid state school systems: at least two years of teaching experience and certification by a state board of education. Their actual record surpasses these minimum standards, however. Some can boast up to thirty years of teaching experience and sixty-five percent hold M.A.’s or Ph.D.’s. One parent pointed out recently, ‘We have had our children in schools in various parts of North America and .England but we have rarely encountered a faculty as well trained, as consistently dedicated to the principles of education and as responsive to the needs of the children. Those at A.C.S. try to apply all those principles, methods and tolerant intellectual attitudes we hear so much about these days. If students do not perform well it is probably their own fault.’

In the Elementary School, children may be seen learning their ‘Alfa, Beta, Gamma’ while nearby others will be learning about the American Indian using the latest audio-visual aid. Dr. Elizabeth Howard, the principal, was a Professor of Education at the Universities of Chicago and Rochester. During those years she served as a consultant to many school systems. She gave up her tenure and is now happy to be applying the fruit of her thirty years of experience at A.C.S.

Over in the Middle School, children are working in the labs, following courses on Ancient Rome and Greece, or sitting around tables in a large, informal math laboratory. The principal here is Dr. George Pimenides, a Greek born in Istanbul (his father was Professor of Biology at Roberts College) who speaks English with a British accent. He is a graduate of Edinburgh University and Peabody College. He taught at the British Council and, in the Greek system, at Anavrita (the school attended by former King Constantine), before coming to A.C.S.

Next door at the Academy students are moving from one class to another, perhaps planning their next theatrical production or field trip, or waiting to see the Principal, ‘Chip’ Ammerman. His association with Greece goes back many years. A graduate of the University of Connecticut, he holds an M.A. in Literature from the University of North Carolina (Chapel Hill), has done post-graduate work in Administration and Psychology and is the co-author of Peanut Butter and Yoghurt, a short, perceptive book examining the problems and adjustments of youngsters in a foreign country.

Coordinating the various activities from the administration offices are Dr. Stanley Haas, Superintendent of the school system and Dr. John Dorbis, the Assistant Superintendent. Both men have an impressive professional -and academic background in Comparative and International Education, Dr. Haas graduated from San Francisco State College in California and received his Ed.D. from the University of California at Berkeley. After serving as an elementary school principal in the Palo Alto Unified School District in California, he became Headmaster at the Overseas School in Rome. Eight years later he assumed his present position with A.C.S. He maintains an active interest in international education as Chairman of the European Council of International Schools.

Dr. John Dorbis, educated in England and France, holds a Ph.D. from the Sorbonne and has completed a year of post-doctoral work at Harvard University. He taught Psychology and Education at the Egyptian State University and the American University in Cairo before coming to A.C.S. in 1957 as Chairman of the Language Department. A specialist in International Education, Dr. Dorbis will be a Visiting Professor at Michigan State University this summer.

CONCRETE evidence of the quality of the system is also to be found in the results of the standardized tests administered to the students. Seventy-five percent of the graduates, as compared to the fifty percent average in the U.S., go on to higher education.

Perhaps the tendency to pay more than lip service to those principles accepted worldwide in educational circles as ‘ideals’, to introduce new concepts in learning, as well as a reluctance to apply older and more formal notions of discipline, account for the uneasiness felt by some of those who view the school from a distance. While people may admire schools such as Bedales in England or the theories behind progressive schools in other parts of the world, many are not prepared to face the non-traditional or informal approach regardless of proven results. An Austrian woman who visited the school recently noted disapprovingly that in her time, ‘children wore uniforms and sat quietly at neat rows of desks, rising only with permission’.

A.C.S. has not gone ‘Summerhill’, however, and in some respects is almost puritanical in terms of actual rules and regulations regarding students’ observance of proscriptions and prescriptions. (In England and North America many schools have abandoned rules against older students smoking on school grounds but at A.C.S. a student may be suspended for several days if caught smoking on campus.)

The progressiveness is to be found on the social level — in the absence of a dress code and in the informal relationship between students and teachers — and on the academic side. The teachers willing to help and guide the students, the material, the programs, the equipment and the incentives are all there. The notion that teachers must ‘force’ children to learn, however, is generally frowned upon. Despite the vast amount of evidence to prove that in the long run children cannot be disciplined into learning, many parents today still seek a school that they hope will perform that function. They will not find that at A.C.S. They will, however, find a faculty and administration unusually willing to devote a considerable amount of energy, empathy and effort to the needs of the students, and responsive to their queries. One startled parent told us that after requesting an appointment to discuss his son’s progress, he arrived at the school and was presented with a carefully worked out schedule which enabled him to see all his son’s teachers during their free periods or between classes. The teachers appeared with grades, papers — and perceptive observations about ‘Johnny’, and voicing disconcerting questions such as, ‘What do you think we could do to help?’

While the school is based on the American system, to consider it an American enclave in Greece is erroneous, as even a brief critical visit to the school soon reveals. From its inception in 1946 as a British School in Kifissia it has served a diverse community. As the British community diminished and the American grew, it became known as the ‘American School’. By 1961 the primary, middle, and secondary schools were established on the Halandri campus. Evidence of its mixed origins and character is still to be found in the names of the schools, known as the ‘Elementary’ school, the ‘Middle’ school and the ‘Academy’, the second and last terms rarely encountered in North America today and the latter, ‘The Academy’ carrying with it echoes of classical colleges. A primary school near the airport at Hellinikon and a school on the island of Rhodes complete the complex.

TODAY the 2100 students come from thirty-three countries and a variety of family backgrounds. One liberal minded Greek-American parent pointed out that A.C.S. provides the cross section of society that was once to be found in the. greater metropolitan areas of America before the upper and middle income groups fled to the suburbs. The majority of the students until now have been the children of the American military, some living outside the U.S. for the first time, others having experienced the transient military life in a number of other countries. In many respects their families, too, represent a microcosm of a mixed society. They come from many parts of the U.S., from various socio-economic strata (from the enlisted to the professional or highly educated officer class), and their mothers are often non-Americans. The remainder of the pupils are from the diplomatic corps and business community. Many of these represent different nationalities and some are of Greek parents who hold foreign passports.

The teachers are also drawn from varied backgrounds. Seventy-eight percent are American. Few, it would seem, trace their descent from the ‘Mayflower’. Some are naturalized Americans, others retain the traditions of their ethnic inheritance. The rest come from Greece and other parts of Europe and the Middle East.

The school is governed by an eight-member Board of Education elected by the parents. Colonel Everett J. Marder, the President of the Board for the last two years, has divided his diverse academic career between the U.S, and Greece. Fluent in Greek, he studied for a year at the Pantios Superior School of Political Science in Athens. He was the only foreigner in his class and perhaps the only American of non-Greek descent ever to study at the school. He studied for another year at the Greek Higher War College. A Master’s Degree (in Later Greek Studies) from the University of Cincinnati was finally added to his collection. Demetrios Alexakos, the Vice President of the board, is a Lieutenant (Reserve) in the Greek Navy, and President of the Dolphin Maritime Corporation. He graduated from the Royal Naval College in Greece as a naval engineer and went on to Columbia University in New York to receive a Master’s Degree in Mechanical Engineering.

This international and varied socio-economic mix has produced a distinctive school. It is, in the words of its own staff, a private school with a public school philosophy. There are no entrance examinations. The only requirements are fluency in English, a parent living in the area, and a sincere interest in attending school.

The students have access not only to a highly qualified and professional’ faculty but to a varied program. Computer Concepts, Mass Media, Ethnic Literature and Photography are but a few courses that supplement the regular and traditional academic subjects. Advanced students may take courses at Deree-Pierce College. There are a bookstore on campus, a student newspaper, three guidance counsellors, a school psychologist, a school nurse. The school also offers evening courses for adults, a language program for Greek high school students, and seminars in Teaching Methods, organized in cooperation with the Greek Ministry of Education, for teachers working in the Greek system.

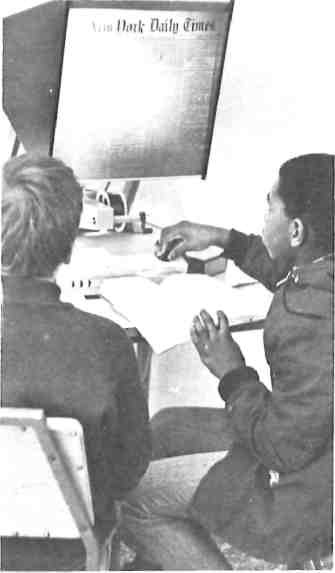

In the ‘Media Centre’, which resembles a large sitting room, there are 11,000 books, dozens of current magazines, records, film loops, film strips, cassettes, study kits, art reproductions, and paperbacks. A student wishing to research his studies may even consult the New York Times, as far back as 1864, on microfilm.

SOMETIME in March of this year another dimension was added to the conglomeration of multi-cultured and international students and faculty when a group of men and women from several capitals of Europe, the U.S.A., the Middle East and Greece appeared on the campus. They examined the fire extinguishers and counted the water fountains and perhaps even the books in the library. They listened attentively to the opinions of students as well as those of the school’s bus drivers. They observed teachers conducting their classes. The seventeen men and women busy scrutinizing the Community Schools represented the Middle States Association of Secondary Schools and Colleges from which A.C.S. first received accreditation in 1965. The M.S.Α., one of the six official accrediting organizations in the United States, accredits 1500 secondary schools and 500 colleges in the U.S. and abroad. Appropriately, the Chairman of the committee was an American of Greek extraction, Kyriakos Constantinos, Superintendent of the Lenapee School District in New Jersey.

‘Basically, we want to find out if a school is doing what it says it is doing,’ he explained when he was in Athens, ‘Accreditation is a voluntary process — a school must ask to be accredited.’

How does one ‘evaluate’ a school such as A.C.S.? The Middle States Association measures each school against the school’s own goals and in terms of the community it serves, Mr. Constantinos explained. The result is not a rating of one institution above or below another, nor is it a negative, punitive process. By identifying its strengths as well as its weaknesses, a school will undergo constructive changes after examining itself within the guidelines of accreditation.

Accreditation is approached with a mixture of eagerness and anxiety when it involves an overseas school such as A.C.S. since the process of applying to a college or university from a foreign school system is further complicated when a school is not accredited. Perhaps its most valuable function, however, is the fact that it forces the administration and teachers to examine their goals and their own performance.

A.C.S. began preparing itself for accreditation approximately two years ago. Committees were formed and re-formed, an estimated 40,000 questions were answered. The official guide book was Evaluative Criteria, a 350-page manual published by the general committee of the national accreditation board, which enumerates in unsparing detail the major areas to be examined. The first step in the process was defining the philosophy and objectives of the school. From that base the other areas were evaluated: staff and administration, school plant and facilities, guidance services, student activities, media services and curriculum.

When it came time for the visit of the committee, the school had, in effect, done its ‘homework’. The twelve-member committee which examined A.C.S. was familiar with foreign community schools. Some of the members are themselves teachers in international schools in Vienna, Paris, London, Rome, Madrid, Waterloo, Isfahan, The Hague. It included such experienced educators as Harry Hionides of Athens College, Maricelle Meyer, the former Director of Studies at the Hellenic American Union in Athens, David Larsen, the Executive Director of the Fulbright Foundation in Greece, and George Salimbene, principal at Pierce College.

For the students, the visit of the committee was, outwardly, just a routine day. To the dismay of some teachers, the overly verbal and nonverbal, high-spirited as well as low-spirited students conducted themselves without pretense in front of the official visitors.

The findings of the committee have now been channeled to Kyriakos Constantinos. By next fall, A.C.S. will know the results of the final report and its conclusions as to where A.C.S. stands today in terms of established, scientific criteria.

The last time we were up there no one seemed to be unduly concerned. The graduating class had begun to receive responses form universities and the results were reason for satisfaction. An International Dinner with contributions of culinary art from members of the foreign community at-large had gone off with great success. A ‘Prom’ was being organized by the Juniors in honour of the Seniors. Held annually at the Hilton, it is a signal for the students to astonish themselves and their parents as well as the faculty by shedding their jeans and appearing like pastel impressions of romantic youth. Meanwhile, the Drama Club, Student Chorus, Music Department and members of the Faculty were planning a production of Pajama Game. If one were to judge from the students’ advance reports, the highlight was to be a jitterbug-cum-shimmy dance sequence performed by six notably staid members of the faculty.

Photographs by Steve Strickland.