In classical times there took place towards the end of December the lesser, or Rustic, Dionysia. Later, the Lenaia, so named after lenos, the cistern in which the grapes were pressed, was celebrated near the temple and the theatre of Dionysos on the south slope of the Acropolis. The Greater, or urban, Dionysia occurred toward the end of March. Today’s Carnival is a continuation of these celebrations.

During the Lesser Dionysia, the ancient Greeks observed the birth of Dionysos, the God of Joy and Fertility, who redeemed mankind from all inhibiting complexes.

On the first day of the lesser Dionysia, the Pithoigia took place. The big pot-bellied jars (pithoi) were opened and the new wine enjoyed. On the second day the ancients celebrated the Choes. They danced, drank, and played with earthenware tumblers full of wine, much as contemporary Greeks dance with a glass of wine on top of their heads when they ‘have kefi’.

On the same day the askolia was celebrated during which they leapt up and down on a wine-skin, askos, as if trampling on grapes to extract the wine. The ritual was meant to symbolise the release of the spirit of the wine; that is, the God Dionysos himself. To add to the fun, the wine skin was smeared with oil, making it more difficult to keep balance. Hence, in modern Greek dances one partner quite often steps upon another’s stomach. The second dancer kneels and bends backwards, like a victim in ancient ritual. Often a dancer without a partner will, in his exuberance, use a chair overturned on its back. With great dexterity he jumps up on the edge of the seat and with jerking movements steps out along the forelegs — always keeping perfect balance. Slowly the seat tilts up behind him until at last he sits back on it like the newly-arrived god Dionysos seated on his throne!

To the same Dionysian celebrations we may attribute the origins of those elaborate steps, or patimata, we see today in dances such as the Tsamikos (the ancient Trochaios), the Zeybekikos (Zeus-Bacchos or Artozeri), the Hassapikos (Anapaistos), the Tsifteteli (Kordax), the Syrtos (Ormos), and so forth. The Cretan dance, with its very high jumps, particularly when it involves leaping up on the back of the chair of a seated friend and springing over his head, is very reminiscent of those well-known frescoes at Knossos which celebrate the Tavrokathapsias, or Bullfight Dance.

On the third day of both Dionysias, there took place the Chytroi (i.e. tureens) during which Dionysos was brought earthenware pots filled with roasted wheat, fruit and vegetables for the souls of the dead, much as modern Greeks offer the similar koliva at Memorial Services. Aptly, the Church Fathers fixed the modern Psychosavvato, the Saturday of the Souls when all the dead are honoured, during the period of Carnival. That men make merry and masquerade at the time when they pay tribute to the dead, may be explained by the belief that the body, being flesh, is only a vessel containing the unchanging spirit of man. In the West, a similar phenomenon is found in the juxtaposition of All Souls’ Day with Halloween.

This offering of koliva at Memorial Services today — as well as its consumption by the mourners — apparently constitutes the closest parallel to the practice of the ancients. Now, as then, it is earnestly hoped that the dead will disintegrate and return quickly to the elements from which man was originally formed.

All over Greece during Carnival, revelries reflect the Dionysian rites of fertility. In the Peloponissos, not far from Nemea, the Byzantine monastery of Lechova rises on the site of an ancient temple of Apollo whose symbol, the laurel bush, still grows in the centre of the monastery’s court. Lechona, means a woman who is in child-bed. Men and women visit the monastery to drink the waters which, since classical times, have been said to increase fertility. A rare old mosaic depicting a stork, one of the ancient fertility symbols, can be seen there.

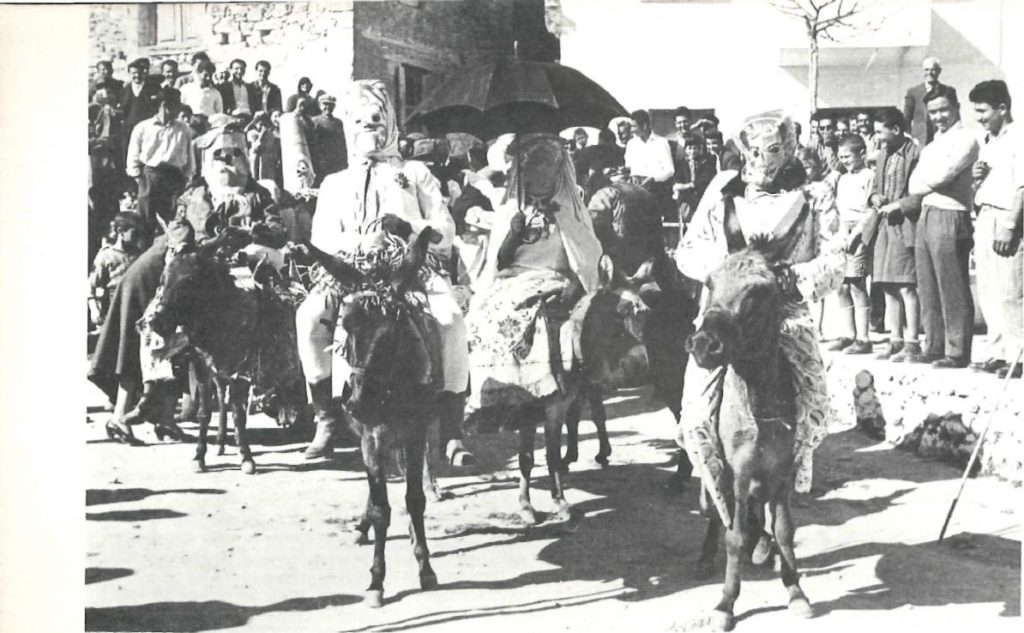

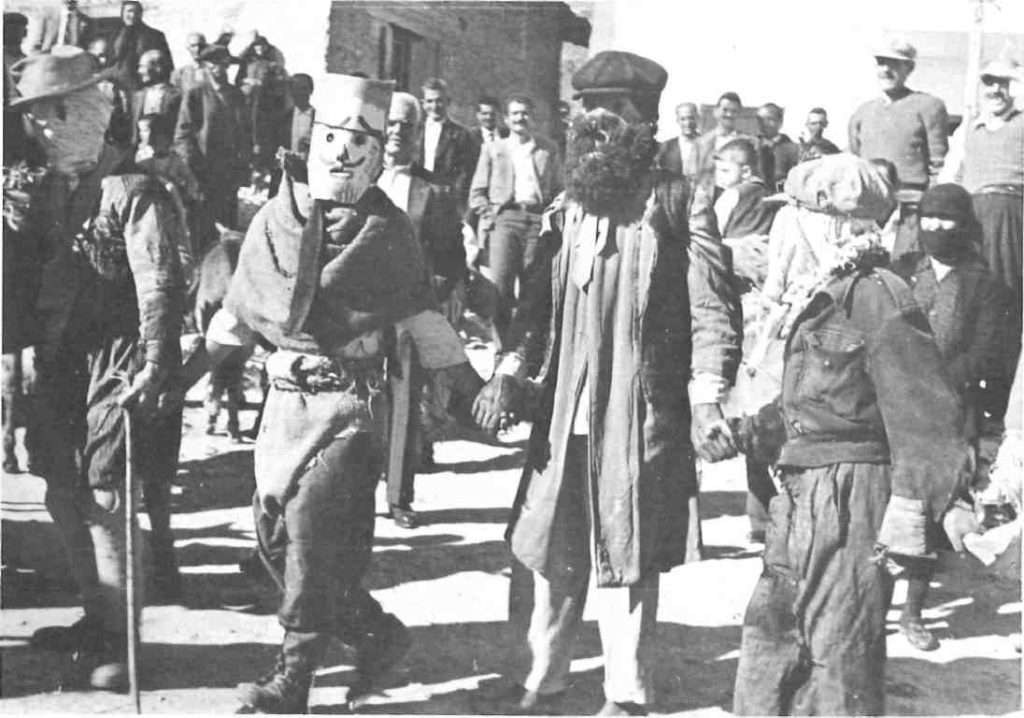

Nearby, at the village of Gonoussa (gonos: offspring) a symbolic, sacred marriage — the hierogamia of the ancients used to be performed. This ‘marriage’, carried out with great mockery, was attended by all the villagers. It was organised and prepared by women under the direction of a revered old hag, but the performers were all men. They rode into the village square on donkeys, the ‘bride’ protected from the sun under an umbrella. All were fully disguised, including the mock-priest who officiated. As is often the case, the revellers dressed themselves in the guises of folk-heroes, historical or legendary, donning masks, for example, such as the ‘death-mask’of Agamemnon or the woolly-beard of Polyphemus. Parts of the marriage rites of today were performed: the ceremony with the crowns (stefana), the burning of incense (in the mock ceremony manure, an allusion to fertilizing, was burned), the procession around the ‘altar’ and ending with the friends of the ‘newly-weds’ joining in the marriage dance.

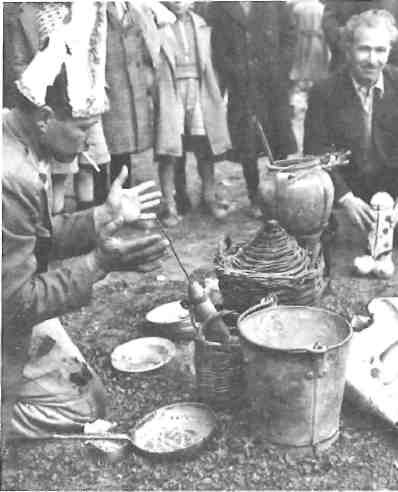

In and about the town of Tyrnavos, near the suggestively-named ancient site of Phallana, they celebrate the manly Bourrani. This name derives from a dish of wheat, celery seed, parsley and similar things which are prepared for the occasion. The ancient dish kykeon, served to the initiates of the Eleusinian Mysteries, was much the same.

The revelry, which begins at the crossroads of Tyrnavos and is continued on the hill of Prophet Elias, is probably connected somehow with Pan and therefore with his frolics. The revellers masquerade in sheep’s clothing and horns. Horns, of course, besides goatishness, may connote, as in the case of certain Minoan and Cypriot figures and of Moses himself, Wisdom.

The distinction of the Bourraniis the emphasis given to objects with phallic symbolism. Most are made of clay, though some are wooden. They are worn on head-dresses and paraded about. Even candles are placed in them. Children join the pranks and learn, no doubt, about the facts — as well as some of the mysteries — of life, in light-hearted good spirit.

Before the Second World War, a Crown Public Prosecutor tried to stop the proceedings. He was seized by the participants, stripped of his clothes and subjected to certain amusing indecencies. The matter was taken to court where it was decided that the Bourrani be allowed to continue in honour of its great antiquity.

The Babos celebrations in Macedonia are better known. On Women’s Day, or gynekokratia, which takes place on January 8, the women take over the roles and duties of men. A braid of garlic, morroton, which is a safeguard against the Evil Eye, is placed around the neck of the village midwife. A phallic ‘schema’, made up of a pair of garlic bulbs and a cucumber, is feted as the centerpiece of the whole rite.

Near Olympia in Elia the kiloumi, a wooden log covered over with a handkerchief, is paraded. (In ancient times, pieces of wood said to have fallen from the sky were worshipped as idols — xoana. The word kiloumi may be derived from the latin ‘sky’, coelum.)

The phallic symbol can be found in most of the Carnival customs that come down from ancient times. Vulgar only to the vulgar mind, it is simply a primitive, though direct, affirmation of life,

In Epirus all kinds of feasts, parades and fairs reproduce the resurrection in effigy or rite (dromenon) of ‘Zaphiris’ who represents the newly-resurrected god, whether it be Dionysos, Adonis or Linos.

These customs, whether derived from Eastern, pagan or Christian tradition, tend to underline, both in their similarities and differences, and by their changing forms and dress, manifestations of the deeper being of man to which they address themselves.

Any interference with these enjoyments — whether they be iconoclastic, puritanical or governmental — is due to a lack of understanding. As the saying goes, ‘Life with no celebration is a long road without any wayside inn for rest.’

At the Bourrani, a dish similar to that offered to the initiates at the ancient mysteries of Eleusis is included in the picnic.

The photographs shown here were taken over ten years ago in 1965.