“I don’t think about how I’m writing. I just write. I do know that some reviewers have called me a Greek Kafka… although I do not accept this. I don’t even accept the title of author or writer. I am simply a common man with faith in people.”

Antonis Samarakis is modern Greece’s most widely translated writer after Nikos Kazantazakis. He has published four collections of short stories since 1954 and two novels. To Lathos (The Flaw) has been translated into over twenty languages. Graham Greene has called it, Ά real masterpiece. A story of the psychological struggle between two secret police agents and their suspect told with wit, imagination and quite outstanding technical skill.’

Arthur Miller has written, ‘The Flawis a powerful work. I only wish some people who profess democracy would read The Flaw and see what it is they actually support. We are all living in a time when words and their substance are very unrelated — to the point of meaninglessness. And this is not only in the question of Greece.’

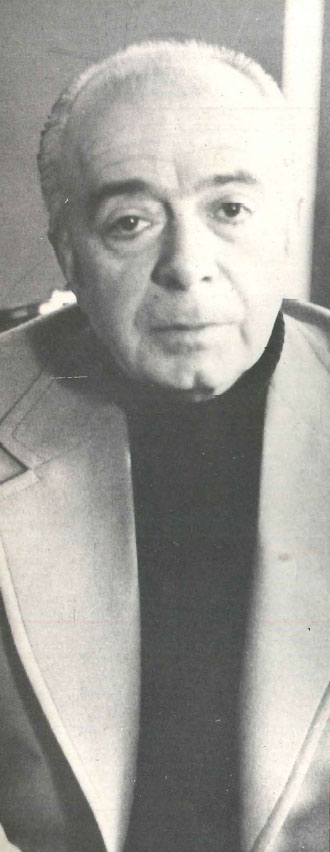

Antonis Samarakis was born in Athens in 1919. He holds a law degree from the university. Between 1935 and 1963 he worked for the Greek Ministry of Labour. He has travelled extensively and worked abroad for the United Nations on labour and social problems in Africa, Brazil and other countries.

‘If I had the possibility to start again, I would try to have two jobs. I read an article years ago in which many authors were asked whether they liked writing full-time, and most said no, it would be bad for their writing… Believe me… the human or social experience of work is very important for a writer.’

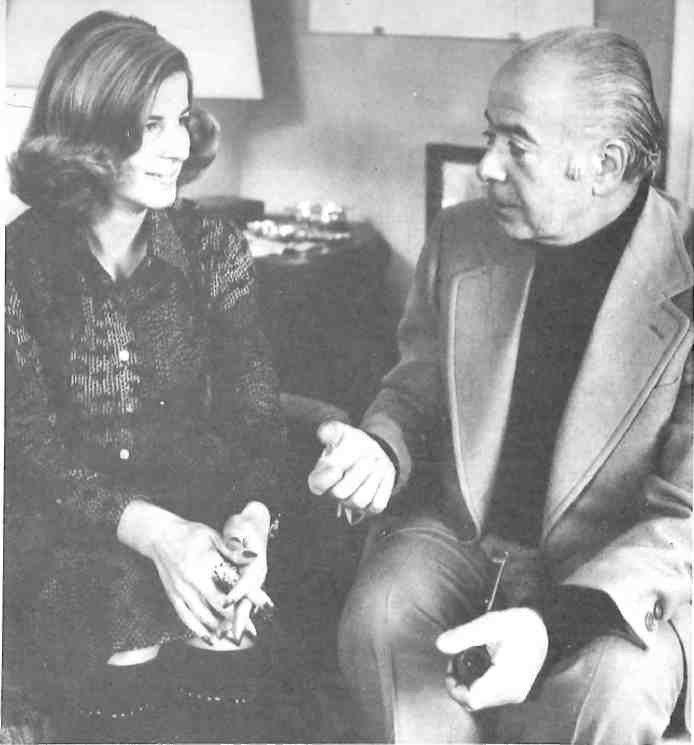

Samarakis is now retired from the Ministry of Labour. He lives in a comfortable house in Kipseli with his wife, Eleni, who is an attorney-at-law. African carvings, Danish woodprints, Greek sketches and pottery — the furnishings of their house reflect their varied experiences and tastes.

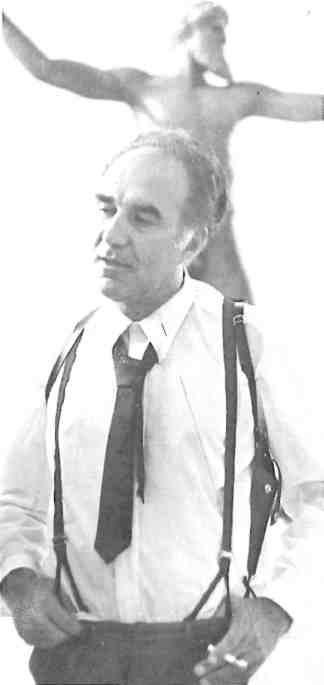

The author holds his favourite pipe but does not light it. He is short and energetic. His eyes are alert, warm, playful. His manner is so gentle and open that it is difficult at times to remember that he is the same man who has written so strongly about the threat of totalitarianism to the common man. He speaks clearly and spontaneously in English although it is not his native language.

‘After I left the Ministry, I worked for more than three years with the United Nations and then on other jobs in Greece. I worked as a slave, for instance, translating the memoirs of Winston Churchill into Greek. It took me three years. I had to have sixteen pages translated every week for a weekly serial… I was exhausted when I finished in 1967, a few days before the Junta.

‘Now I feel uneasy because I don’t have a concrete job. I detest theory. I detest philosophy. I have a passion to do something concrete. I’m trying to find something else. It is more difficult now because I am married and I want my wife, a lawyer, to have her own career. But I don’t want to be just a writer.’ Samarakis’ characters, it has been said, are anti-heroes, common people. The author agrees.

‘That’s because my life has always been with the common man. I don’t like to be called a “writer”, or an “author”… my heart is just like it was when I was a child. I’m always touched by the reactions of the man in the street, the common man… For example, I would never write even one sentence for people like the heroes of Marcel Proust. Ί started by writing poetry. I was ten years old and lived in Athens. I wrote maybe fifteen poems and published four or five in magazines, but I was never a professional writer because I have never had the mentality of a professional writer. I don’t like to write every day… In 1953 I wrote my first collection of stories, Wanted: Hope. I wrote these stories because some of my friends with whom I used to go to tavernas heard me mention my ideas and told me I must write them down. I wrote them, really, to be free of my friends!’

Samarakis’ first book appeared in 1954. The author himself paid the publication costs, and peddled it to the bookstores, practises common in Greece today. He met with indifference, and it was not until the famous critic, Evangelos Papanoutsos, devoted an entire column to the book on the front pages of To Vima that it became a success.

‘With writing you never know, you can write five or ten good books and then the eleventh may be a zero…’

One critic has said that Greek writers find the short story easier… partly because they do not have the time since most hold other jobs.

Ί wouldn’t have written more novels even if I had more time… I wrote Danger Signal while I was working at the Ministry. It depends on the idea. I knew from the beginning that both of my works would be novels. Of course I had not planned everything. I just had some general ideas of the plot. I didn’t know the ending either. You see, I am not a slave of my own art.’

Samarakis’ writings are international. He explains that he has written in this way because the serious problems of our times are general and universal and not limited to any particular nation. In both The Flaw and The Passport no specific country is mentioned.

His use of the Greek language is a blend of demotiki, katharevousa and foreign words that have entered Greek usage. His work has the virtue of being easy to read and I ask if he has written as a ‘common man’ in order to gain a larger reading public. He responds that he began writing as a reader and not as a writer. The books he enjoyed most were those written in a simple, direct manner. A writer can be modern without being confusing, he suggests. He believes that the best modern art is clear, straightforward, direct.

Ί believe that language expresses everyday life. Language must be and is flexible. You cannot stop foreign influences… I don’t believe in boundaries or limits. Foreign words and expressions don’t need passports to travel! My style, for instance, is not literary in the usual sense. It is literary in another way. It is the style of the simple, of the everyday. I “detest too many adjectives and what I call “sauce”.

Ί admire Simenon very much. Gide, for instance, said something really revolutionary. He said that if young writers really want to be good writers, they should read Simenon! And of course books by Simenon are not really detective stories, they are human stories.’

Edwin Jahiel of the University of Illinois has written about the cinematic qualities of Samarakis’ prose. Has he been consciously influenced by the cinema? Ί can’t say yes and I can’t say no’, he replies. ‘The fact is that I love cinema and I have seen many films since the time I was a child. But as for my writing, I have never thought about the cinema. I have written my work exactly as I was feeling. If critics now say they have discovered some cinematic elements in my work, this makes me happy, of course, because I believe cinema is popular art and can do many things for a better humanity. Cinema can influence masses more than literature… People who have seen a movie can make a revolution. I remember as a child I saw Pancho Villa, with Wallace Beery, more than thirty times. I remember that everyone, adults and children, was crying. When we left the cinema we were ready to make a revolution ourselves. But I wrote my books without thinking of cinema. I had no need to think of cinema because my life is full of cinema!’

In addition to the widely publicized The Flaw, several of his other works have been made into films. The River, a short story, was made into a film by Nikos Koundouros. It was produced by Americans with the music composed by Hadzidakis. Made in both Greek and English, it won first prize in 1960 in Thessaloniki and in Boston. The English title was This Side of the River. Tetragono (The Rectangle) was made into a film in 1964 with music by Xarhakos. The Flawhas also been made into a TV drama for Japanese television and another story, Ideas Bureau, was used for a Canadian television production.

‘It’s my opinion that a writer must stay in his own country to write. I stayed in Greece even when I finally got my passport from the Junta’, he says, referring to the episode which led to another story, To Diavatirio (The Passport).

While other Greek writers such as Kazantzakis have wrestled with their nationality, it does not seem to be an issue with Samarakis. He is Greek. He belongs here. This is his country and he examines its society with an analytical eye.

‘Much Greek propaganda says that Greece is the country that gave the light of civilization to all other countries. But I wonder if that’s really what happened. Then I wonder if Greece perhaps gave away all of these lights of civilization but forgot to keep one for herself. I know very well, with all of my heart, that there is no culture in Greece. This is a problem for young people in Greece. One professor recently told me in Thessaloniki that they have the feeling that they are just civil servants. You understand me. If you have a professor of the university saying that he is a civil servant, then it is impossible to continue any kind of dialogue.’

Samarakis expresses the surprise he felt in 1960 when he visited American universities. There he saw students sitting outside discussing whatever they wished to discuss with their professors.

In Greece, he comments, such dialogue never happens in such a way. The problem of Greek education is not a bureaucratic one, but the difficulty of finding professors with pnevma — spirit.

‘Culture on the one hand means something concrete. You can check on culture with certain cultivated people. At the same time, culture is something which is not concrete, something you cannot check or prove. It is an atmosphere, a climate.

‘It exists with the young generation which is a fantastic generation. Most of those who read good books and appreciate the theatre and cinema are very young. Youth is always in the front line. Remember the Polytechnion, for example. The young generation is what gives me optimism today. Culture is a whole climate. You see, my idea is for all of us to swim in a sea of culture. We don’t swim at the moment, however. We just stick our fingers in to see if the water is cold or not. Of course the common man and young people are not guilty of this. The guilty ones are all governments.’

Samarakis remarks that even the fight for freedom is a sign of culture. He was dismayed that so many showed apathy towards the Junta during the first years. Really cultivated people, he maintains, cannot accept such stupidity and suppression. Culture means more than having read many books and to have been successful at exams. It is a mentality, a spirit, ‘a movement of the soul’.

In 1944 Samarakis, a member of a resistance group, was arrested by the Nazis but escaped. During the past seven years he was an outspoken critic of the Junta.

‘In 1970 the government refused to renew my passport. This event became the basis for my story, To Diavatirio (The Passport) which was first published in the anti-Junta collection, Nea Krrnena 2. After the refusal, the Secret Service often “invited” me to go to their offices. Sometimes agents would show up at my house at 5:30 in the morning for no reason. So I published the story to get back at them.’

The charges brought against him, however, were related to articles he had written before the Junta came into power. Ί had, of course, spoken and written aginst the Junta on many occasions, but I was accused because of an interview I gave in 1965 to a foreign publication in which I said the problem of political prisoners must be solved. They also accused me of saying in my writings that I was against war and even against nuclear war!’

He throws up his hands in a gesture of disbelief.

‘You see, to be sincere, we must accept that all of us are guilty. The colonels were not a fruit that appeared just like that; they were the result of many things that happened in the past.

Ί was invited to respond to their charges in my own handwriting. But I refused from the beginning. I told them, “Don’t expect any type of correspondence with me. You refused me a passport? Alright, refuse me, but I will do whatever I can against you.” If they asked me I would even have refused to write what day it was. This went on almost every week for eighteen months. Finally the Secret Service came to me and said, “Why don’t you just say a few words in favor of the regime?” And I told them they were silly to ask me.

Ί made two appeals against the government to the Council of State. My first appeal was against the silence of the regime which had given me no written accusation at first. Two months later the regime sent its refusal but sent the answer through fifteen different police districts with “address unknown” stamped on it! This was, of course, just to make me lose time.

‘But after I got this written answer, I sent another appeal. I wanted to make sure that my case would be discussed before the Council. Months later the case was discussed. I won.

‘Three months later my dossier was carried across the street from the Council of State to the Passport Office, a five minute walk. At the Passport Office they told me I needed a new application. They asked me to come the next day. I went the next day and they told me, “Mr. Samarakis, the Secret Service would like to see you again.” That is when I told them, “I will never see the Secret Service again. They know where I live. If they want to arrest me, let them come!” I wrote a new demand for a passport. Three more months went by without an answer.

‘Finally I got a rude call one day to return to the Passport Office. This time I received my passport. They discovered that they could not fight me in the way they wanted to fight me. I also think the international pressure was very important.

‘Now, of course, I can write anything I want to write. But I don’t think that the fight for freedom is finished. On the contrary, it is not easy to suddenly have a democratic country after almost eight years of a totalitarian regime. And secondly, I believe and I know that Greece was never a really democratic country. Never. I think here in Greece we have had trouble in modern times ever since Greece was independent from the Turks. First we had the establishment of a foreign king and his wealthy supporters. Then the Greek Church has always made a really democratic Greece difficult. And even today it is the same. Don’t forget that during all of the years of the Junta, where were all of these famous heads of the Greek Church? They never dared to say just one word in favour of all of the victims. And don’t forget that these heads of the Church were very secure in their positions; the colonels would never have dared to do something against them. But in spite of their security, they never dared to say anything. So they are “dead” persons for me.’

Samarakis is a man who writes with a serious purpose, but he makes much use of wit and satire. He has used this technique in The Passport especially, because he feels that at some point all totalitarian leaders make themselves appear ridiculous. He gives the case of Greek television as an example. For years the democratic governments of Greece argued the pros and cons of having television with the result that nothing happened. When the colonels took over, however, they swiftly began television broadcasting on a large scale on the theory that they would be able to reach all Greeks including those on remote islands and in mountain villages. The members of the Junta appeared daily on television opening new buildings, kissing babies and greeting foreign dignitaries. Although they thought they were making themselves popular, he notes, they were exposed to the nation as the ridiculous figures they were.

Many writers have stated that all people are political creatures whether they are aware of this fact or not. Samarakis agrees. Everything is political. A decision not to be involved in politics — and he belongs to no political movement himself — is a political act. He thinks of himself as a critic of all governments.

‘In my 1965 interview which the Junta used against me, I said that the Communist Party must be allowed to exist, although I am not a communist. And I said that the intellectual and spiritual level of the common man is on a much higher level than that of the king, the church leaders, political figures, university professors and writers. And I made a point to mention the king’s name first! Do you know that when the king was married, he spent millions and millions of drachmas for the most expensive champagne? Why did he do this when Greece is a country without many hospitals, without good schools, without most of anything! And Frederika (the Queen Mother) received flowers everyday from the Middle East on a special plane sent to get them. I detest all of them. I detest all totalitarian regimes. I know very well what I say and that’s why I say that a writer must be free.’

Speaking freely, he states that if we are to have a better world, capitalism must be destroyed together with bureaucratic Christianity. He points out that the real miracle of Christ is that He has survived despite the Christian Church.

‘Would Jesus be head of the Christian Church if He returned today?’ he asks with an ironic look in his eye.

What function does his writing serve? Does he write for pleasure or to save the world? Samarakis explains that he writes because he has a need to express himself. Ί think this is the basis of any art and any human activity’, he adds. But writing is not his whole life and perhaps he will stop writing tomorrow. What he enjoys about the written word is the possibility it offers of dialogue between writer and reader even if the reader is unknown.

Arthur Koestler has written, ‘His novel, The Flaw, has wheels within wheels which carry you from a Schweik-like start into a Kafkaesque nightmare redeemed by the masterly ending.’ Yet Samarakis, despite universal acclaim, says Ί don’t even accept the title of author’.

He has spoken often of the common man. He thinks of himself as a common man writing for other common people. What and who is the common man? The working classes, the middle class?

‘The person who is not a member of a “gang”, either a literary, political or capitalist “gang”. The common man is the man who is able to have a certain interior freedom and who is without the idea that he is something very important in this life.’

The Filming of the Flaw

A political suspect is arrested in an unidentified country by agents of the National Security Department. In order to break down their prisoner the agents hatch a ‘flawless’ plan. On the long trip by car to the capital city, engine trouble (part of the plan) forces the agents to separate. The Interrogator remains overnight in a nearby town with the suspect, but as the plan is executed, the Interrogator begins to discover a flaw: he comes to appreciate the honesty and humanity of the suspect and to doubt his own role in the National Security force.

Most of The Flaw, to be released this month, was filmed in Greece last summer. The French-German-Italian production directed by Peter Fleischmann stars Michel Piccoli as the Interrogator, Ugo Tognazzi as the Suspect and Mario Adorf as the Second Agent.

Samarakis explains that the international success of his novel led to numerous film offers over the past few years from European and American producers. Most noteworthy was that of Luis Bunuel who wrote to the author from his home in Mexico City in 1971 that he wished to direct the film. The letter was awaiting Samarakis when he and his wife returned from their first vacation in many years. Samarakis hurried to contact the dynamic Spanish director but discovered that Bunuel had in the meantime committed himself to other projects. Bunuel’s script writer, Jean-Claude Carriere, wrote the screen adaption of the novel with Bunuel’s approval, nonetheless. The expatriate Spanish director has also written about the novel for the press. ‘The Flaw interested me enormously’, he wrote, ‘the structure is both novelistic and cinematic; truly interesting. The Flaw is ad hoc for the cinema.’

Marcello Mastroianni, Franco Nero, Gian Maria Volonte and Michel Bouquet were among the performers who wanted to participate in the film but could not because of prior commitments. Fleischmann even persuaded Samarakis to take a screen test and, convinced that the writer had hidden acting talent, tried to cast him as the Chief of National Security. The novelist was flattered but declined to accept a role he felt should go to a professional Greek actor. He does appear Hitchcock-fashion in one scene, however. Dimos Starenios plays the part of the Chief while other Greek actors include Themos Karatsanis and Vangelis Kazan.

Filming in Greece is a pleasant enough assignment for a foreign crew but the Flaw group had its surprises while working on this anti-totalitarian project. On one occasion, for instance, they arrived in Nafplion in the early hours of the morning. The set-men quickly installed in the platia a huge emblem of the imaginary Regime featuring a clenched fist and a double-headed Minoan axe. Its appearance, suggesting a new coup only a few weeks after the fall of the 21st of April Junta, caused great distress to the unsuspecting townfolk the next morning. Two older women happened by, looked up at the new emblem with horror, crossed themselves, uttered a few desperate Panayea mou’s and fainted.

The novel is generalised in terms of location, time, and nationality, but the film cannot escape looking somewhat Greek because of landscape shots and scenes such as one in the Zappion. The Greekness is down-played, however, in order to maintain the universality of the novel.

The Flaw, like most films based on novels, is not a slavish imitation of the written word. Critics have noted, for example, that The Great Gatsby would have been a better film had director Jack Clayton not relied so heavily on Fitzgerald. Samarakis explains that, ‘Personally, my idea was not for the film to be a bad one because it followed my book word for word. I wanted a good film based on my novel.’

The music was composed by Ennio Morricone who wrote the score for Sacco and Vanzetti and other films. Fleischmann is not a well-known director, but the few films he has directed have shown an eye for cinematic detail and humanistic concern. FJis first, Scenes de Chase en Baviere, won two awards at Cannes in 1969. The Haw will be entered in the 1975 Cannes Festival in May. If the product is as good as the ingredients we shall be hearing more about this new work.