A representative of the telephone company complained the other day that local service is poor because Athenians spend more time on the telephone than any other people in the world. We were not surprised and are forced to admit that we have been contributing to this record. We resent the spokesman’s suggestion, however, that we spend most of the time gossiping. In fact, we never gossip. We spend our time listening to others gossip, and, what is more, if we are to judge from the confessions of most of our friends, half of Athens spends its time listening over those forever-crossing-wires, to the other half of Athens gossiping. Our own line has become mysteriously tangled — through no fault of ours — with that of our gardener’s who lives nearby. We spend most of our time listening to his wife gossiping, more often than not about us. We are not complaining. Quite the contrary, we are thankful, for it forces us to do a little soul-searching and to make the occasional attempt at self-improvement which we would probably never do otherwise.

When we are not eavesdropping, we spend our time on the phone answering wrong numbers and getting busy signals after we have dialed the second digit. The former activity has greatly increased our circle of acquaintances and consequently enriched our lives. When on rare occasions friends do get through to us, we usually say, ‘Hang up at once. We are listening to the gardener’s wife!’ If she happens to be otherwise occupied, we allow ourselves a brief chat with our caller but are usually interrupted by a third voice yelling obscenities at us and demanding to know what we are doing on their line. At other times, one of our voices just fades away and we begin dialing zero to bring it back, or, worse, we are suddenly disconnected. When this used to happen in the old days we concluded that whoever was tapping our line did not approve of what we had said. Nowadays, we can only blame it on OTE.

A Constitutional Proposal

We have studied carefully the highly informative articles on Greece’s Draft Constitution by Dorothy Peaslee Xydis which appeared in the Athens News in January. A study of comparative constitutions, we suppose, is highly appropriate to the present situation in Greece, but our minds were not set at ease. Mrs. Xydis notes, for example, that the Costa Rican constitution proscribes the Army as a permanent institution. The Ecuadorian constitution, meanwhile, places all sorts of prohibitions on its army. Given the history of these countries, we wondered what sorts of conclusions we are supposed to draw from that information ! Constitutions, it would seem rarely reflect the peculiarities or the particularities of the history of the people whose liberties they supposedly safeguard.

We do not pretend to be experts on Constitutional law but we are enthusiastic students of behaviour and it is our belief that the new constitution should reflect our national character and our national experience. National character is one thing that cannot be changed, and institutions must be adapted to the personality of a society if they are to survive.

The question immediately arises as to how we are to approach a study of the Greek character insofar as it is applicable to the drafting of a constitution . We modestly propose that a committee of psychologists, sociologists, and statisticians be appointed to produce a sort of White Paper on Customs and Mores. By simply observing and recording the most mundane practises, social scientists are able to arrive at sweeping conclusions about entire nations and such a study, we feel certain, would be of more value to the designers of our constitution than scholarly comparisons with other documents.

They might begin with a Comparative Study of Road Manners. Consider the ways in which we differ from others in this area alone. In some countries, for example, people drive on the right, while in others they drive on the left. In Greece this is one of the few areas where we take the middle road: we like to straddle the white line, regardless of where it appears on the road, what it’s intended to indicate, or where it goes.

In most countries, drivers slowdown when the light turns yellow. Here in Greece it offends our filotimo suggesting, as it does, cowardice, and we speed up just to show it who is boss.

Generally in most parts of the world, policemen shout at miscreant drivers. Here it is the other way around. When the traffic code is broken, policemen throw their hands up in indignation, gesticulate animatedly, or simply shake their heads in disapproval, and rarely have the heart to stop a car and face the wrath of a driver who has just gone through a red light. Some years ago we watched a policeman directing traffic near Syntagma Square. The drivers methodically ignored his directions and a massive jam developed. Observing the tangled mess, he delivered one grand mounza, (‘five fingers’) retired to the sidewalk and left the drivers to extricate themselves.

The use of directional signals in most countries implies that the driver is going to go in the direction indicated, but here it may mean the opposite, that the driver forgot to turn it off, or that he accidentally turned it on as he was gesturing at other drivers. As far as gestures go, the only hand signal used is the mounza which is unique to Greece and can mean any number of things.

What conclusions the social scientists will come to, we cannot and, in fact, hesitate to predict. We feel certain, though, that the information they amass will be interesting and invaluable to the legal scholars.

January Celebrations

THE ceremony of the blessing of the waters on Epiphany, celebrated annually on January 6th, almost ended in a riot this year in the Thessalian town of Elassona. The ceremony is celebrated on the banks of the local river. Until recently the ancient custom was observed: the cross was thrown into the river by the Bishop and retrieved by young swimmers who paraded it through the town. During the dictatorship, however, a new practice was adopted. A string was tied to the cross and by pulling this the Bishop himself was able to retrieve the cross unaided by local youth.

This year Bishop Sevastianos, following the more recent practice, tied a string to the cross and threw it into the water. The traditionalists, however, were too quick for him. Several young men leapt into the river, cut the string, seized the cross and paraded it about the town. The Bishop called the police. Arrests were made and the cross was again retrieved and returned to him. When the citizens gathered and demonstrated outside the house where he was staying, the Bishop fled with the cross to his seat at the Monastery of Olympiotissa, and the youth of Elassona set out in hot pursuit. At the monastery a confrontation took place and the Bishop finally promised to return the cross to the people so that they might carry it around the town the next day.

Retrieving the cross from the seas and rivers occurs only on that one day of the year but retrieving coins from the New Year’s pitta (the cake-like bread baked with a coin in it for the holiday) tends to drag on for the entire month and occasionally continues into February. There was hardly a single news broadcast on television in January that did not show a pitta being cut at a ministry, a club, or a regiment.

We decided to run one of our informal surveys to see just how many hours are spent by an individual observing the tradition. Our first call was to our local bank manager but he could not speak to us. They were at that moment doing the honours with their pitta. We next called our lawyer but he was attending the ceremony at a firm where he is a member of the board. A call to a business friend produced the information that he had cut the pitta at his office, attended several at the offices of company’s with which he does business, the New Year’s Day ceremony at his parents’ home, of course, and — we were not under any circumstances to tell his mother — he and his wife had also cut their own on New Year’s Eve. Several calls in the evening produced no results. They were all to executives who were all graduates of Athens College, and they were all up in Philothei at their Alma Mater cutting the Alumni Association’s pitta.

On the Road to Kifissia

The thrills encountered driving along the road to Kifissia are many and various, and the joy felt on reaching one’s destination alive serves to enhance the experience.

A fender bashed in by a rollicking truck emerging from a factory between Halandri and Amaroussi, an exhaust pipe left behind in one of DEI’s unmarked holes, a bumper carried off by a taxi rushing a maternity case to the hospital, are all part of the fun.

There are subtler pleasures, however: gazing, for example, at the old age homes that have sprung up along the way — and wondering if you will ever reach those Golden Years. Our favourites are Elegant Relax Palace No. 2 and the delightful, serene Maison de Cheveux Blancs with its motorcycle rental shop conveniently located on the ground floor.

Among the cultural amusements to be enjoyed is the great variety of sculpture to be seen in private gardens and in front of markets dealing in statuary. One can only marvel for instance at the garden of sculptures at No. 63 (Amaroussi) which rivals the courtyard of the Archaeological Museum; or the statuary market a little farther up specialising in wild life to decorate the garden — pink pelicans, swans, fish, and frogs, to name a few. Then, of course, there are those fine reproductions, (in plaster of paris we believe) of Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs.

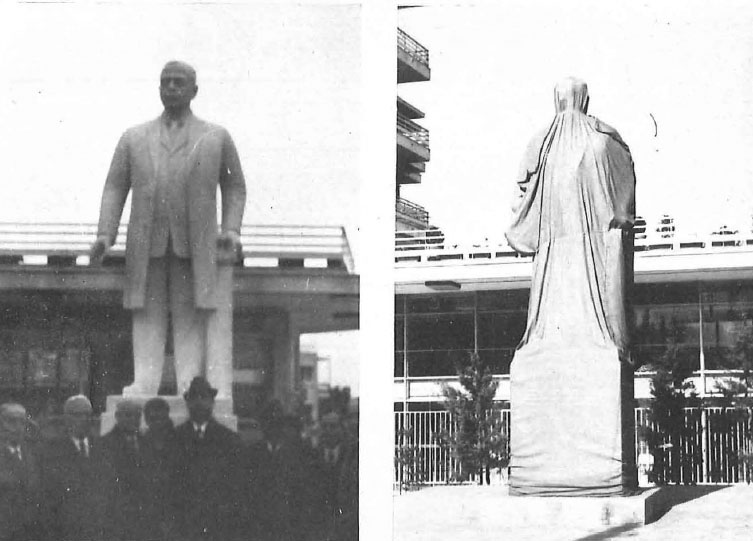

For the more serious student of modern sculpture, there were, up until recently, modellings of the human figure which took on their own monumental significance. The road and various stretches were known always by several names: Leoforos Kifissias, Odos Marathonos, Odos Melas, and sundry others. Suddenly the entire stretch was re-named, Leoforos Ioannis Metaxas and just as suddenly memorials to the famous dictator of the 1930’s — who was much admired by the recent junta-government — sprung up as the townships along the route vied with one another to produce a renaissance in Greek sculpturing that would match the Age of Phidias. The Ionic grace of Halandri’s Metaxas complimented the Dorian vigour of Amaroussi’s Metaxas, while the commanding, full-figure of Kifissia’s Metaxas was a masterpiece of Papadopuddlian Art.

Alas, with the recent changeover, the Metaxas statues have been put into storage or under wraps. Now, after driving past the strategically located ΚΑΤ emergency hospital (and nothing can match the surge of relief one feels driving past it and not into it), one is greeted by a hauntingly draped and bound figure welcoming you to Kifissia itself. If you have survived the trip up to that point, it’s guaranteed to scare the last remaining wits out of you.