On the other hand there is another group of painters who adhere closely, almost mechanically, to the last great years of Palaeologue art and produce works of such exactitude that at times it is almost impossible to distinguish between the icons of the fourteenth and sixteenth centuries.

Two contemporaries of Damaskinos reflect these divergent developments. John Kyprios was working in Venice at approximately the same time that Damaskinos was frescoing the Church of St. George and was possibly responsible for some of the work in the church. A number of icons by his hand survive, one of which, an Annunciation, is in the collection of the Benaki Museum. While iconographically it conforms closely to a type that was prevalent during the late Palaeologue period — the Virgin standing to receive the angelic salutation — there is a certain ‘naturalness’ about the proportions of the figures that betrays an attempt to contemporize along the lines of then current Western ideals. One might be tempted to look for an influence from Classical art, especially in the statuesque pose of the Virgin and in her restrained gesture of acceptance which contrasts sharply with the more dramatic and almost theatrical gestures found in many Palaeologue icons. More probably, Kyprios was attempting to introduce a Latinate element into the style of this icon. This becomes apparent if it is compared to icons utilizing the same iconography that were executed either before or after this panel. An interesting example of this latter type can be found in the Benaki in an Annunciation by Tsanfournaris of the seventeenth century.

Another contemporary of Kyprios and Damaskinos was Andreas Ritsos who executed most of his work in the sixteenth century. Ritsos was in many ways a more accomplished painter than Kyprios and also less ambitious in that he remained closer to the tradition of Byzantine panel painting which shows no trace of direct Western influences or affectations. He and several other painters of the sixteenth century were so intoxicated with confidence and commitment to the ‘classical’ Byzantine ideals of painting that it is almost impossible at times to differentiate an icon of the sixteenth century from one of the fourteenth century.

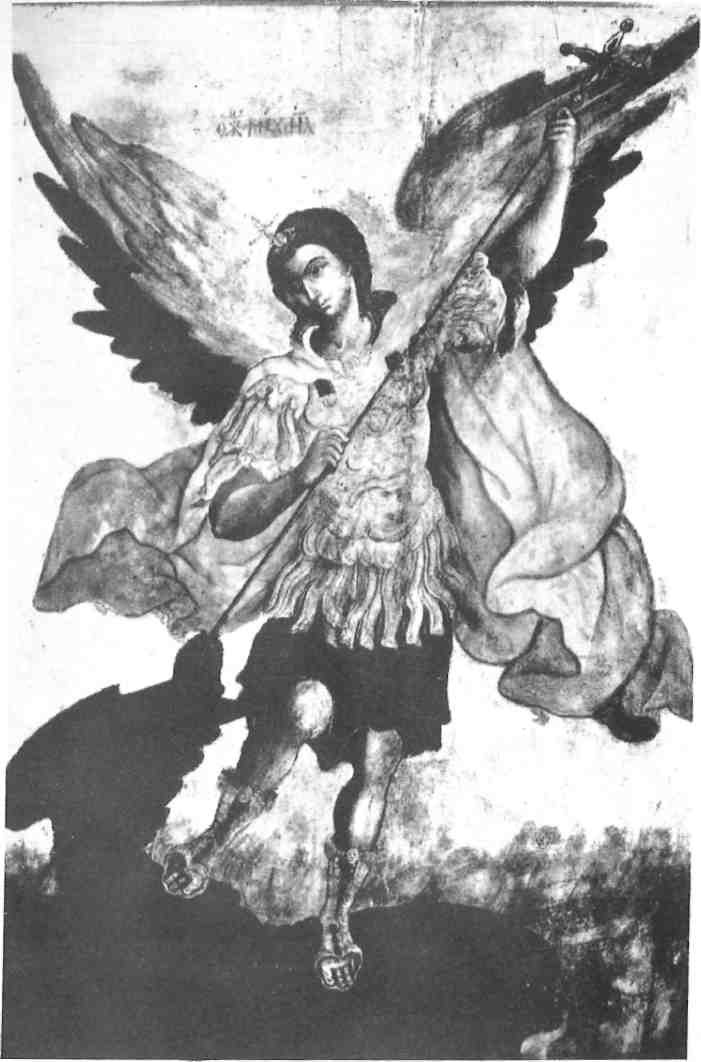

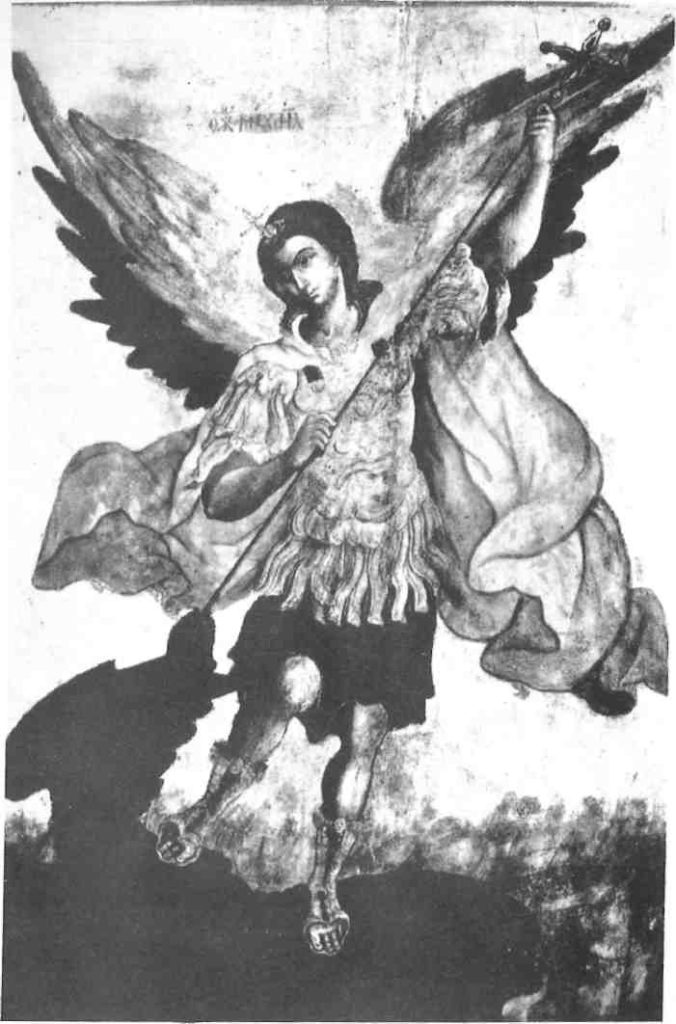

Increasingly in the course of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries one notes a greater influence of Venice and the West in the icons of the great Christian painters, although many of them show remarkable versatility, switching styles, techniques, and iconography to suit donors or quite possibly their own whims. Some of the greatest names among these painters are Lombardos, Pavia, Tsanfournaris, and Moskos. Poulakis stands apart from them as perhaps the most ‘baroque’ in mannerisms and his nervous almost itchy compositions are intricately composed of convolutions in figures and landscape.

Toward the end of the seventeenth century one notes a reaction on the part of apparently unknown painters who express perhaps the Orthodox Church contracting in response to increasing Western influences. Many of the icons of this century adhere closely to Byzantine traditions in colour as well as sense of form and balance. There is, however, a frigidity that certain fear and self-consciousness which characterize the period in general. The Greek Church was undergoing difficulties. The working relationship that had initially existed between the Ottomans and the Church had broken down as a result of overt attempts made by the West to endanger this balance. The Jesuits on the one hand and the Turks on the other would eventually force Orthodoxy into a state of atrophy that is reflected in some icons which clearly attempt to recreate a past glory. By the eighteenth century the Ottoman Empire began to show signs of the fatal illness that would leave it the ‘Sick Man of Europe.’ Its social and economic structure began to break down, affecting inevitably the Church which lost not only revenue but also its prestige. Great painters of icons disappeared. The icons of this period are the work of unknown monks or laymen who were clearly ignorant of the canons governing the art. In response to this artistic decline, the ‘Painter’s Handbook’ by Dionysios of Fourna reappeared. A guide to iconography, it became the ‘bible’ of icon painters, though so few icons of value were being produced that it was virtually irrelevant. Oddly enough it was after the Greek War of Independence that the art of the Eastern Church was dealt the final blow. The desire of Western Romantics to see, in every Greek, a possible descendant of Pericles, infected Greeks themselves so they began to disparage their Byzantine heritage. Greeks became highly self-conscious about the peculiarities of Byzantine art that were unintelligible to Europeans. Lacking confidence in their tradition, they literally began to wage war against that heritage. Western influences emerged in the introduction of polyphony in church music, in atrocious painting of the St. Suplice style, and in the introduction of oil painting techinques which transformed the crisply accentuated character of icons into soupy imitations of the sentimental religious art of nineteenth-century Europe. The deterioration was complete by the end of the century.

What with the classically oriented archaeologists and the freshly Europeanized Greek, almost all of the important small Byzantine churches of Athens had been destroyed or ‘redone,’ their facades and interiors unrecognizable under newly applied plaster and paint. It is worth remembering that the Church at Daphne was still being used as a stable well into the present century, its mosaics disintegrating into an effluvium of manure.

Despite the efforts of individuals, there has been no revival to speak of. The inner religious tension and experience that gave the art of Orthodoxy its depth and contemplative character has vanished in the wake of materialism. Ours is not a religious age and we can expect no more than what has happened. Icon painting is today nostalgic, personal and isolated. The great tradition is, for all practical purposes, dead.