Post-Byzantine art evolved directly from the intellectual and artistic atmosphere prevalent in Byzantium on the eve of the Empire’s collapse in 1453. The art of Byzantium continued to evolve despite the political and military downfall of the Eastern Roman Empire. Reflecting as it did the religious idealism of the Eastern Orthodox Church, Byzantine art escaped the great disaster that befell the civil structure of the Empire. Rather, art shared with the Church the role of maintaining some remnant of imperial greatness among the Christian Greeks of the Ottoman Empire.

Under Ottoman domination, the Orthodox Church’s peculiar integrity of purpose and identity was guaranteed by none other than the Sultan Padishah himself. Under the Fetiheor Conqueror Mehmet II, the Church fared comparatively well. The Christian millet of the Ottoman Empire was organized directly under the Ecumenical Patriarch of Constantinople. For the first time in centuries the Orthodox Church was to become thereby fully re-united in the Near East.

Mehmet himself, part Greek, gave the Church its new Patriarch — Gennadios, the former George Scholarios. In January 1454 Gennadios was invested with the Cross, Staff and pontifical robes of the patriarchate by none other than Mehmet himself with the words, ‘Be Patriarch, with good fortune, and be assured of our friendship, keeping the privileges that the Patriarchs before you enjoyed.’

The immediate consequences of the conquest on the art of Orthodoxy resulted more from economic and religious strictures than from any hostility on the part of the Turks. Unable to express themselves in the decoration of church interiors, artists were restricted to icon painting or to decorating churches and refectories in the great monastic centres. Some of these, such as Mount Athos and St. Catherine’s on Mt. Sinai, were almost autonomous within the Ottoman Empire. In centres such as these, Christian monks carried on many traditions in painting and religious writing.

The term ‘Cretan’ has been used by most scholars to distinguish the dominant school of painting during the Post-Byzantine period from the 15th to the 17th centuries.

The study of the Cretan School is fraught with problems. One of these is the fact that peculiarities of technique and style can be traced back to Byzantine art of the fourteenth century. Thus the Cretan School can be seen as an unusual continuation of a trend in art long overshadowed by the older and more fashionable Macedonian School favoured by the court and intelligentsia of Byzantium during the Palaeologue period (1261 to 1453). The style and techniques characteristic of the Cretan School appear in some fourteenth century icons and several frescoes found in the Peribleptos and Pantanassa churches at Mistra. Two techniques that characterize the peculiarities of the Cretan school are the use of dark pro-plasma (under painting for flesh tones) and small, sharp, individually distinct strokes of paint to highlight features. Moreover, works of the school show a greater idealism of an almost mystical nature.

Icongraphically one finds that there is a marked tendency to keep to older, more accepted schemata and scenes. There is none of the monumentality of form or composition that one finds in the Macedonian School of the fourteenth century. Rather, paintings of the Cretan School seem more like miniatures expanded to cover walls, as in the frescoes at Mistra.

While most of the painters of the Cretan School were natives of Crete, there is little if anything to indicate that the School developed appreciably on the island itself. The numerous churches of Crete are frescoed in a peculiar style and technique that seems to have died out during the Venetian occupation and were never revived. In other words, the

Cretan School appears to have developed within the mainstream of Byzantine art, to have achieved a certain character, and then, after the Fall of Constantinople in 1453, to have been transferred to Crete. It was here in the hands of Cretan painters who worked not only on the island but in Venice and Athos as well, that it underwent its final development. The historical evidence that we have at our disposal supports such a scheme of evolution.

Crete suffered greatly under the Venetians and the Orthodox Church was more severely proscribed than even under the Turks. The Venetians’ hostility arose from their belief that Orthodoxy was heretical. Turkish attitudes were formed less on theological considerations but reflected instead current social or economic hostility toward the millet of the Christians. This Venetian intolerance probably drove many painters from Crete to Athos. As a result, we find on the Holy Mountain some of the earliest examples of the ‘School’ in the fifteenth century.

The first known Cretan painter working on the Holy Mountain was Theophanes the Cretan in the sixteenth century. Theophanes’s work is characterized by a peculiar fusion of Macedonian iconography with distinct peculiarities in style and technique characteristic of the ‘Cretan School.’

After Theophanes’ time, Mt. Athos seems to have been inundated by painters from Crete who worked in a similar manner. At least ten refectories, chapels, and churches were decorated in the course of the sixteenth century.

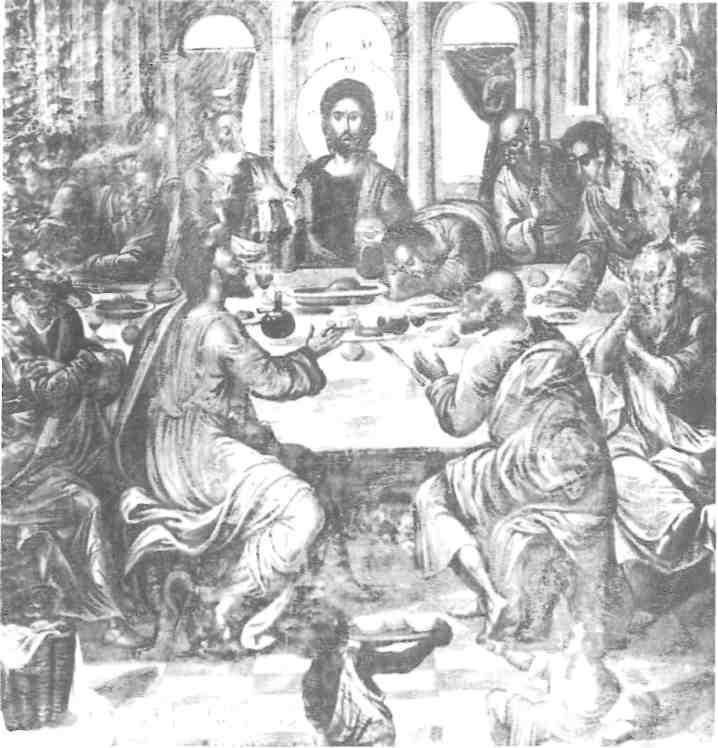

In the work of many of the Athonite painters one can detect, as early as the sixteenth century, the influence of the West. Theophanes’ ‘Last Supper’ at the Lavra on Athos, painted in 1546, shows the figures of Christ and the Apostles behind a long rectangular table reminiscent in some ways of da Vinci’s ‘Last Supper.’ ‘The Massacre of the Innocents,’ painted by Theophanes in 1535 at the Lavra, is a peculiar fusion of the traditional Byzantine iconography with specific figures taken directly from the ‘Massacre’ scene by Raphael now in the Vatican. It would seem that Theophanes was influenced by copper engravings which were widely circulated in the sixteenth century. In the work of George Catellanos at Meteora one notes definite Western influences, particularly in the Nativity where the Virgin kneels in adoration, a pose completely foreign to the compositions of earlier Byzantine artists.

The most representative work of the Cretan School is found not in frescoes but in the icons. The study and analysis of iconic development is greatly aided by the fact that many of them are signed and dated. One of the greatest of the Cretan icon painters was Michael Damaskinos, the major portion of whose work was executed in the latter half of the sixteenth century. Damaskinos’s career was divided between Crete and Venice. His early work in Crete, about 1570, is characterized by a close adherence to the general tradition of late Palaeologue art. One can already detect, however, a tendency toward realism which is harshly at odds with the more idealistic character of Byzantine painting. In the panel of St. Anthony, now in the Byzantine Museum in Athens, the pose of the Saint is rooted in late Byzantine tradition. The rendering of the hands, with knuckles and veins protruding reveals, however, a contrived realism that was characteristic of contemporary Western painting.

Between the years 1579 and 1584, Damaskinos was in Venice where he had been commissioned by the Greek community (most of whose members were of Cretan extraction) to decorate part of the Church of St. George of the Greeks. It would seem that while in Venice he fell victim to Italianate influences which had already tempted him in Crete. The icon of the Last Supper, now in the collection of the Cathedral of St. Minas in Herakleion, is a product of these years. The figures are arranged about the traditional round table of the Last Supper in a more or less conservative manner. Under the table, however, one notes clearly a pair of dogs, while in the foreground appear a small blackamoor and servant and on the floor a basket and towel. These genre elements are quite foreign to the art of Byzantium and reflect the growing influence of Venice and the West on the art of the Orthodox Church.

That Damaskinos was especially prone to these influences, not only in style but also in subject matter, can be seen in another panel at St. Minas which portrays a Divine Liturgy. Traditional Byzantine elements of iconography are jumbled together around a large composition of the Holy Trinity. Christ, the Dove of the Holy Spirit, and God the Father are shown in a manner that was not only foreign but was even canonically forbidden by the Eastern Church.

Such liberties both in iconography and theological speculation might be personal and reflect nothing more than the individualistic spirit of the age, which is also expressed by the signatures on the icons. On the other hand it might indicate a certain lack of confidence felt by the Orthodox Church of Crete. The traditions of the Church were succumbing to the pressure of Rome brought to bear on sections of the island by the Venetians. Such a lack of confidence was not, however, an isolated phenomenon.