And the whole of the ancient harbor resounded with the peal of church bells, and with shouts and cries and sobs:

‘Goodbye… goodbye!’ ‘Kalo taxithi… good journey!’ ‘Farewell, children… farewell!’ It was six days after Easter. A dozen tiny boats were putting out to sea, bound for the sponge beds of Greece and North Africa. Each boat carried from eight to twenty men — the famed sphoungarades (sponge divers) of Kalymnos. They would stay away for seven long months, risking death or paralysis to tear sponges from the bottom of the sea.

Kalymnians have dived for sponges for as long as man can remember, but today that tradition is for the first time in danger of being broken. After all the Kalymnians have endured — disaster and pain beneath the sea, starvation and oppression above it — it is ironic that their way of life should be threatened by a well-meaning scientist who discovered how to spin a synthetic sponge. That his sponges are not much good doesn’t matter: they are cheap to produce; housewives buy them.

Kalymnos, a Greek island ten miles long and five wide, has always been synonymous with sponges. There are farms and tangerine groves and a hot spring, but they keep only a handful of people alive. There is virtually no tourism. Sponges are what the island lives on, but today Kalymnos’s once-proud 15-million dollar sponge industry has seen its gross income shrink to less than a million. Each year fewer and fewer boats go out, from the hundreds of yesterday. There is not enough work for all the divers and sailors on the island. Consequently, many of them must emigrate to the factories and restaurants of Australia, West Germany and Canada. Earlier this century a Kalymnian could emigrate to America and continue his old way of life, diving for sponges in the Gulf of Mexico. It is ironic that those immigrants who settled in Florida should contribute to the economic death of their birthplace. In fact they are now taking so many sponges out of the Gulf that America buys only one-fifth its former amount from the divers of Kalymnos.

Kalymnos may be dying but it is not dead yet, for its people have always been brave, tenacious fighters. This goes not only for their ancient history (which records battles against Byzantine, Frankish, and Turkish rule), but for their more recent struggles against Italians and Germans. When the Italians invaded the island in 1935, the Kalymnians resisted them with hunting rifles, sticks and stones, and harpoons. They continued to resist all through the occupation, even to the point of pulling their children out of school when the Italians suppressed the teaching of the Greek language.

Later, when the Nazis came in 1943 to build an airfield for their pending paratroop assault on Crete, many Kalymnians died of starvation on the island. Others risked U-boat-infested seas and fled by caique or sailboat to Turkish Bodrum three hours away. From there they were sent to Aleppo and then to refugee camps at Gaza. Eventually many of the sponge divers ended up fighting with the British army or working for the Allies in Egypt, salvaging sunken ships.

The sponge divers recognize only one master: the sea. They go out to battle against it year after year, with courage and fatalism. They are bold ones, the pallikaria of Kalymnian songs and folklore. The camaraderie of the divers is fierce and intense: they have gone through terror and humiliation, triumph and success together. They call their work thulia: the ancient word for slavery. It haunts them. The sea haunts them. It makes wild men of them. When the boats return to Kalymnos in November, the tavernas are jammed every night. The divers gamble and drink recklessly, ferociously. Most of them go broke soon after Christmas and are obliged to leave on dangerous winter cruises to see them through until summer. Always they seem to be living in a kind of subdued horror of their work.

There are three kinds of sponge divers: the skafondros who dive wearing a full suit and helmet; fernezos who wear the helmet but no suit; and barcas who dive almost as exactly as their ancestors did three thousand years ago. Such writers as Oppian, Aristotle, and Pliny observed the first barcas at work, and the following are some of the fascinating details which derive from their writing:

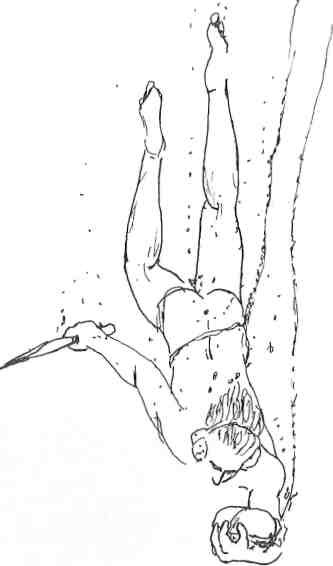

A barca first puts oil in his mouth and auditory canals. Then he soaks sponges in oil and fastens them over his ears. Then ties a rope around his middle and goes down, with only two tools in his hands, a knife and a heavy stone. As he plummets down his ears begin to pain. He hits bottom and spits out the oil, which rises all around him lighting up the water. Then he knifes a sponge from the rocks, and as it bleeds a nauseating liquid which is offensive to smell, he lets go of the stone (which is attached to a line) and swims back up with bursting lungs.

TODAY’S barcas of whom there are still a few, no longer carry oil in their mouths and ears, but they endure the same ordeal as did their ancestors. They think nothing of making two or three hundred dives a day, often at depths of one hundred feet. The powerful pressure places a strain on their lungs and ears and heads, and often they come up bleeding from the nose and ears. After year of this exacting, strenuous work, many of them go partially blind or deaf.

The sponge divers continued diving naked into the sea until 1866, when a French scientific diving expedition under Dr. Alphonse Gal arrived and recruited a group of Kalymnians to test a diving suit invented by Roquayrol and Donayrouze. It was called the Aerophore. The diver wore an air reservoir strapped to his back which received air that was forced down through a rubber tube into a mouth¬piece, and the air came out at the correct hydrostatic pressure for every depth. Moreover, he could detach the pump line and walk about freely for a short while. The Aerophore was so advanced that the development of all modern diving gear can be traced directly back to it.

The introduction of the Aerophore not only revolutionized the sponge industry but nearly started a full-fledged civil war on Kalymnos. The group of divers who first used the new equipment returned with such a huge harvest of sponges that the ordinary divers erupted into violence. Riots ensued in which the traditionalists smashed all the diving equipment they could lay hands on and beat up the men who had used it. But such Luddite-type protests could not, in the long run, hold back technology. By 1870 some 300 sponge divers were using diving apparatus of one kind or another.

Unfortunately, much of the equipment used in the following years was either technically inferior to the Aerophore or was employed by the men without proper training and instruction. Sieve’s helmet suit, for example, killed ten of the twenty-four men who dove with it in 1867 and incapacitated most of the others. Not only did the suit lack a regulator that could furnish air pressure as needed, but the divers believed they could stay down for hours in it sometimes at depths of 150 feet. This, of course, proved fatal.

Unlikely as it may seem, the work of the barcas is less dangerous than that of the skafendros and fernezes, who never know when the air line might break. If it does, and if the diver fails to utilize his helmet’s safety-valve in time, the suction of the pipe will strip away his flesh in rags which stream right up the pipe, leaving a skeleton in a rubber shroud. This rarely happens, though. What the divers fear most is nitrogen poisoning, or the ‘bends.’ If a diver is stricken with it—usually because he has stayed down too long or ascended too rapidly — he can be paralyzed for life. Of the 14,000 inhabitants of Kalymnos, some 1,500 are victims of the bends. Those crippled after 1948 draw a small compensation from the government; the others live by doing odd jobs, and on remittances from relatives abroad.

“The safest way of diving is with air bottles on your back,’ said one of the divers. ‘It’s also good to have a depth-gauge so that you can control your ascent yourself and allow plenty of time to pass off the nitrogen in your blood underwater. But all that equipment is very expensive. Few Greek divers can afford it. Also, it’s easier to work in a full suit and lead shoes because of the strong currents in the Aegean.’

So the sponge divers, making the best use they can of their often obsolete equipment (some air compressors are held together by string and rubber bands and their diving suits show more patches than a clown’s costume), sail to the far corners of the Mediterranean to fish for sponges. They leave their beautiful village with its cube-like, quilt-colored houses dug precariously into flanks of the high brown cliffs ringing the harbor, and head toward Rhodes and Crete, Malta and Libya.

For seven months it will be the same. The day begins at 4:30 in the morning. With the sun not yet showing, the light is dust-grey, the air cool. Someone on the deposito — mother ship of the fleet or two or three or five diving boats — gets breakfast ready: coffee and a hunk of paximade ( hardtack). Its captain, who has advanced each diver about 300 dollars and has paid for the provisions and licenses allowing them to sponge in foreign waters, stands at the prow looking down into the softly rocking sea through a glass-bottomed bucket called a yalass. While he searches out a good bed, the first diver of the day suits up. The others busy themselves with one chore or another, talking all the while.

The older divers talk of their first summer, 35 years ago, and the men who sailed with them. ‘By God,’ one says, ‘they were divers then! Remember Stotti Georghious?’ He was a barca who made what may still stand as the deepest free dive ever made by a human being. He went down over 200 feet into the sea to slip a rope around the propellor of a sunken trawler. At that depth his lungs were squeezed by seven atmospheres of pressure into the circumference of a thigh! Then there was John Latari who dived into the mouth of a huge shark and was vomited out; and Costa the Crazy who jumped overboard in his suit and lead shoes and was found walking along the bottom, blowing bubbles.

By 6:30 the first diver has gone over the side, plummeting down swiftly, signal rope and air line trailing. The boat moves in a slow, tight circle under the morning sun. While one diver is down,another begins suiting up. The boy on the air line methodically calls out the divers depth — ‘ikosithio’ and the colazaris, the man in charge of the signal rope, relays the information down to the diver. Each of the divers makes at least three dives a day, staying down anything from twenty minutes to an hour each time.

When he ascends he empties his bag of pungent smelling sponges on the deck. These black blobs are then trampled on with bare feet, trimmed, and rinsed in seawater. After pierced with a thick needle and threaded on rope and tossed over the side of the boat to be further washed by the sea, they are scrubbed again, cleaned, and put into burlap bags and delivered to the deposito.

Meanwhile the returned diver has stripped to the waist and reached for a cigarette. ‘If you don’t reach for a cigarette immediately after coming up, you’re in trouble,’ one diver said. ‘It’s a sure sign that something is wrong with you.’ This something wrong is usually nitrogen poisoning, another sign of which is small red or black marks on the chest or back. The divers examine each other carefully all day long, soaking out those tell-tale marks, If a man breaks out he is not allowed to do any more diving for the rest of the day.

The time passes slowly. This is work which by the end of the season becomes a fist pounding down on all human sensibilities, rendering everything private and fragile into nothingness. A dozen-odd men are confined to a boat which does not even have a head. The heat will shrivel their skin; pus will harden in the scabs of ugly sores; brutal African winds will scour everything with red gritty sand; their diet will sicken them — worms in the hardtack, sour water, inevitable fish soups. This is what the divers will know — all for twelve or thirteen hundred dollars a year, if they are lucky.

It has always been like this for the sphoungarades. ‘No ordeal is more terrifying than that of the sponge divers and no labor more arduous for men,’ wrote Oppian back in the third century B.C.

It is no different today. Despite the fact that one or two of them might die over the seven month season, that some five or ten will return to Kalymnos condemned to a life of uselessness by the crippling after-effects of the bends, the sponge divers are still going out.

‘We will keep going out,’ said one of the divers. ‘If we don’t dive for sponges, we will dive for something else — algae, other minerals, who knows? Men will always need things from the sea and the Kalymnians will go out after them.’