ICONS OF THE PALAEOLOGUE PERIOD

In three areas of the former Empire, what might be called governments – in exile were formed. At Nicaea a relative by marriage of the Comnenids — Theodore Lascaris — established the Nicaean Empire. In Epirus the Angeli under Michael I, who was also an in-law of the Comnenids, created what became the Despotat of Epirus with its capital at Arta. Finally, there was the Empire of Trebizond, ruled by direct descendants of the Comnenids, the ‘Grand-Comneni,’ an empire destined to outlive the final collapse of Constantinople in 1453.

The most energetic and effective of these Byzantine sub-divisions was the Empire of Nicaea. By reason of its proximity to Constantinople, it was in the best position to launch an offensive to re-establish Byzantine authority. On the death of the Emperor Theodore II Vatatzes in 1255, an ambitious aristocrat by the name of Michael Palaeologue seized the throne and in 1261 entered Constantinople in triumph to assume the Purple of Byzantium under the name of Michael II. He proceeded to destroy effective Frankish power in Greece so that by 1265 the boundaries that had existed prior to the Fourth Crusade were virtually restored.

The political and military history of the Palaeologue Dynasty that ruled from 1261 to 1453 is at best depressing. Encroaching Ottoman conquests were only part of a problem aggravated by the Mongol invasions, the existence of a powerful Serbian kingdom that had arisen on former Byzantine territory, and the Catalans. The most debilitating factor was the West’s desire for revenge masked as demands for union of the Eastern and Western churches. Byzantine emperors were forced to make humiliating trips to Venice, Florence, and Rome where they were offered ‘deals’ as payment for mercenary troops.

By 1391 the situation for the Byzantines was made acute by the Ottomans’ annexation of greater Thrace, Bulgaria, and the Serbian kingdom. Geographically, the empire was reduced to a small section of Thrace, the area around Constantinople, Thessaloniki, and the greater part of the Peloponnesos — the centre of a despot ruled by the heir apparent from Mistra. Between these three cities — Constantinople, Thessaloniki, Mistra— the last cultural and religious revival of Byzantium was effected.

In general, one can distinguish the continuation of two distinct currents in the religious and cultural life of Byzantium during this time. On the one hand there was the Imperial Court with its dependents and clients in the aristocracy and the imperially appointed higher clergy who, pragmatically, looked toward the West for support against the Turks. Their somewhat cynical approach to life and their understanding of the problems of survival led them to accept, at times, the formal union of the two churches under the primacy of Rome. This pro-Western inclination expressed itself in intellectual circles as a growing interest in Aristotelian philosophy and scholasticism.

Against these Westernized theologians were ranged the lower clergy, the monks and the more conservative elements in the church as well as the mystics and laity. Their Orthodoxy had been unaffected by iconoclasm or by the Latin occupation. Their fidelity to the older traditions of the Eastern church continued to be expressed as a deep dependence on Patristic and, thus, Platonic thinking.

These two currents, represented on the one hand by the Westernized intellectuals and on the other by the monks, mystics, and laity, point up a basic paradox in Christianity: the opposing traditions of Hellenic rationalism and the more intuitive religious experience arising from Semitic roots. Out of these opposing traditions, an uneasy but operative situation was forged. Regarding the ultimate question of all religious life — the union of God and Man — the Eastern church based its theology on a flat acceptance of mysticism and Grace as opposed to the more Hellenistic assumption that reason and intellect lead man to God.

Undoubtedly the most eloquent exponent of this Orthodox and apophatic tradition was the great 14th century mystic, Gregory Palamas, the defender of the Hesychasts. The Hesychasts have a tradition in the Eastern church that reaches back to Evagrius of Pontus, one of the early Christian mystics. In essence the Hesychast doctrine, like Buddhist and Sufi theories, regards intellect and reason as initially hindrances in the search for God. The intellect creates a ‘screen’ of images that prevents the Ultimate Reality from shining forth, of Itself, within the divinely grounded substance of man. There is good reason to believe, in fact, that Buddhism, through Sufism, had a strong influence on the techniques used by the Hesychasts in ‘stilling the heart.’ By watching the breath, by centering the attention on the area of the heart or navel, they sought thus to lose their egoistic individuality. The end of this quest was the moment of revelation when the Light of Tabor radiated through their entire being. By losing themselves, they thus found ultimate union, absorbed in the Ground of their own individuality. Palamas, in defending the Hesychasts against the rationalists of the court and the Western educated Barlaam, stands as perhaps the best rebuttal to those who deride such a path or quest as fruitless, the result of mere fuzzy thinking: he was himself a formidable intellectual who succeeded in vindicating the Hesychast position in the Eastern church.

Whereas the icons of the Palaeologue period largely reflect these mystical tendencies in religion, being closer to the monastic traditions and schools of painting and intended for private religious devotions, the more important frescoes, executed during this period in Yugoslavia, Greece, and Constantinople, are much more characteristic of the humanistic and rationalistic tendencies favoured by the imperial and aristocratic donors. In these frescoes, great masses of colour decorate monumental compositions that emphasize the human mission of Christ, his miracles and his suffering and Passion. In the Church of the Chora in Constantinople, Theodore Metochites, the donor and court official of Andronicos II the Elder, certainly helped in planning the mosaics and their subjects, all of which were drawn from Apocryphal Gospel accounts in the scenes representing the life of the Virgin. The sources of inspiration — i.e., the Pseudo-Gospels of Matthew and of the Armenians — had never been included in the canon of Christian scripture precisely for the reason that they now appealed to many Byzantines. That is, they were more humanly drawn and only concerned secondarily with the mysterious Redemptive Act central to the Christian Mysterium.

One notes a quite different element at work in the icons of the Palaeologue period. The iconography is more conservative just as the style of painting is much more reserved and delicate than that of the frescoes. Even more striking is the idealistic and mystical atmosphere that prevails in both the rendering of faces and settings. Figures are elongated and delicately conceived. The faces are sombre, at times reflecting a deep inner preoccupation. A stillness, an almost contemplative, centred repose reflects a profound concentration of energy.

Icons characteristic of unique religious experience can be distinguished immediately from those that reflect influences proceeding from the Comnenian and Macedonian periods, or from those that reflect the more humanizing tendencies prevalent in the court — best exemplified by the frescoes of the so-called ‘Macedonian School’ of the fourteenth century.

Three icons to be found in collections in Athens best represent the influence of mysticism in the art of the Palaeologue period.

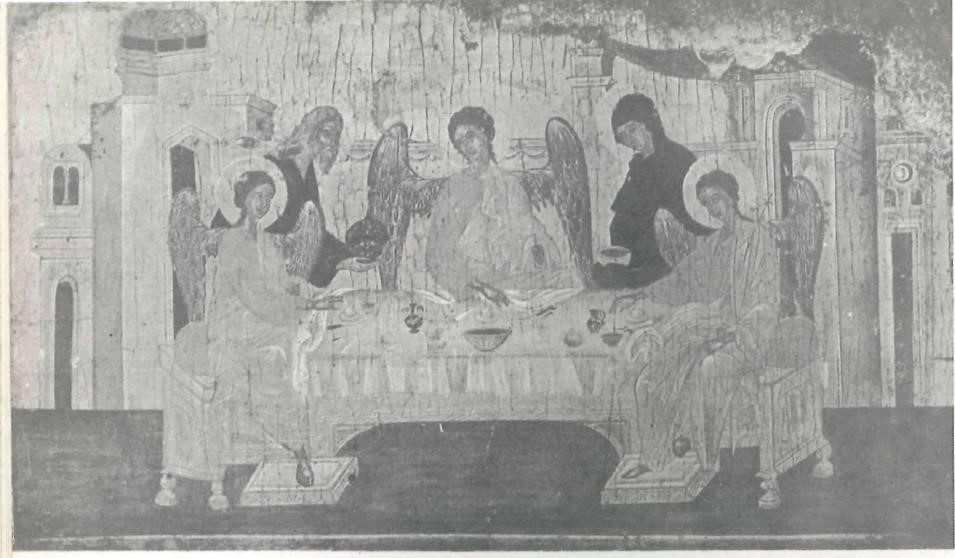

Much of the idealism and elegance of the period, dominated by a prevailing mystical ‘mood/ is to be found in a rectangular panel of the fourteenth century at the Benaki Museum. The subject is a comparatively common one in Byzantine art: the Hospitality of Abraham at Mamre. Based on the text of Genesis (XVIII, 1-16) the scene is set out of doors with the three angels seated around a table. Arranged at the angles of a triangle, their positioning reflects the traditional Christian understanding of the event as a revelation or ‘type’ of the Trinity. Abraham and Sarah humbly posed in dark garments offer food to the heavenly visitors. They stand on either side of the central angel thus creating a completely symmetrical composition. This geometrical balance is characteristic of many Palaeologue icons. Despite the ornately embroidered tablecloth, the bone-handled knives and forks, and the two iridescent glass bottles with fishbone patterns, it is obvious that this is no ordinary dinner. Nor is it conceived in the traditional Byzantine manner in which the Trinitarian implications of the text are secondary to the more humorous aspects of the event — Sarah laughs within the tent when she hears that she is to be the mother of Isaac (the name Isaac or more correctly Itzhaq is based on the Hebrew root for ‘laugh’). In this icon, Sarah and Abraham offer food to the angels as though they were placing votives on an altar around which officiate three priests — or perhaps more properly, the Three Persons of the Christian God-head. The recounting of the event, its ‘historicity’ so to speak, is ignored; what is stressed instead is the Divine significance of the event under the oak at Mamre: Abraham encountering the Mystery of the Trinity and pleading for humanity at the throne of Implacable Justice.

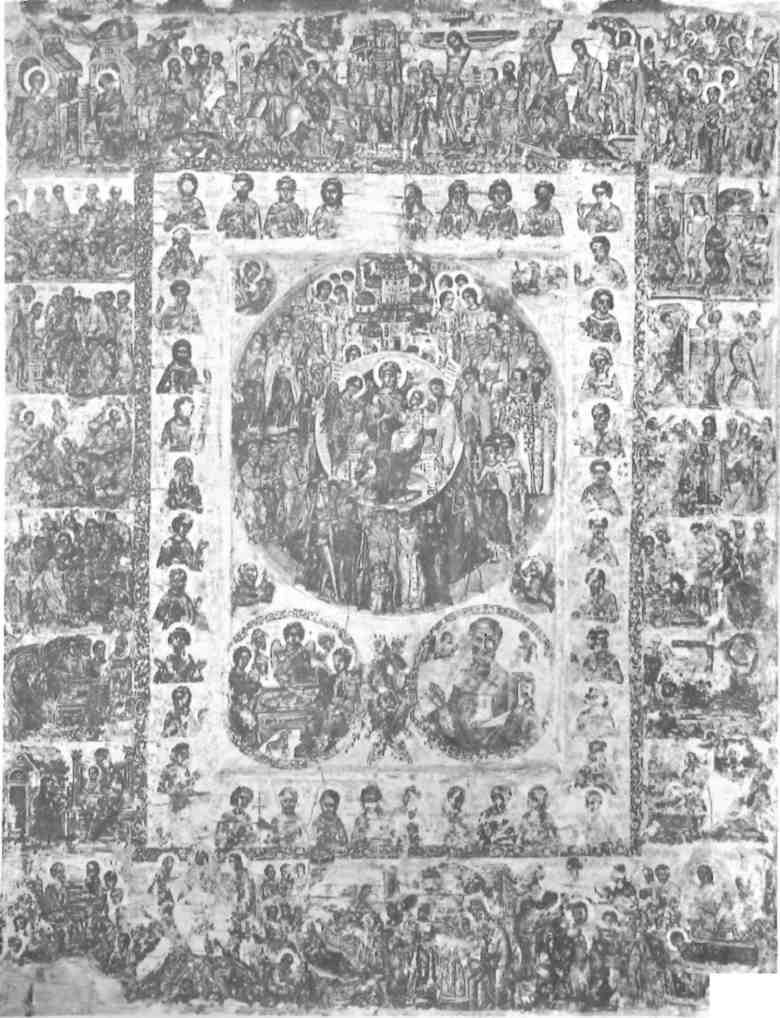

A somewhat controversial icon of the fourteenth or fifteenth century is found in the Byzantine Museum. The subject is taken from a hymn written by St. John of Damascus, Ί thee all heaven rejoices,’ referring to the ‘platytera Virgin Mother of God’ whose womb held the infinite God-head. The title ‘Platytera’ is applied to images of the Virgin seated with the Logos in her lap and surrounded by angels in attitudes of obeisance. At first glance this icon almost appears to be a Tibetan or Buddhist Mandala with concentric circles (the heavenly sphere of dominance) of angels (the minor divinities) and saints (bodhisattvas) all worshipping the still Heart of the composition that rests in the lap of the Virgin-Mother. It is the entire church (the Sangha) schematized in its dependence on the true source of its life.

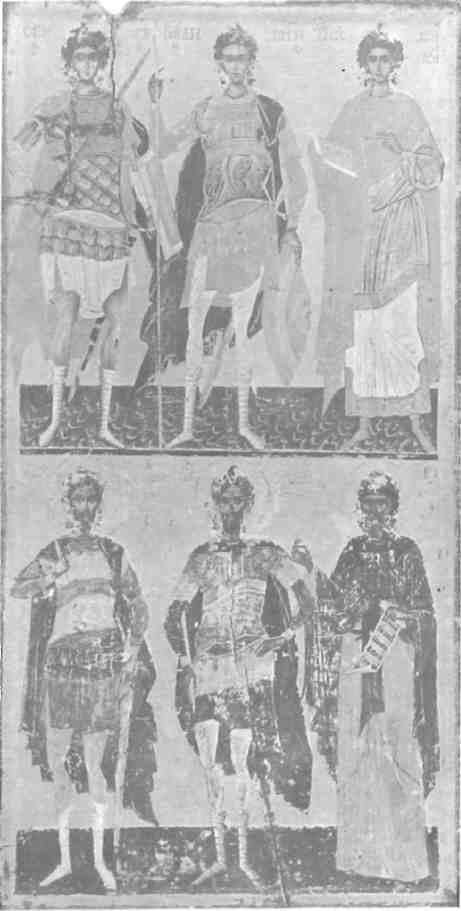

Another icon in the same collection, also from the fifteenth century, is a long narrow panel divided into two horizontal zones each containing three saints. The upper figures are, from left to right: St. George, St. Dimitrios, and St. Penteleimon. On the lower zone are: St. Theodore Stratalites, St. Theodore of Tyron, and St. Anthony of Egypt.

Though many of its elements are derived from deeply rooted Byzantine tradition, the icon’s most striking feature is the flat, linear conception of form that is given volume by sharply accentuated highlights casting a veil of light against the figures. While form and stance produce a recognizable humanity, the expressions and weightless bodies, seemingly drawn upward by the head rather than supported by the legs, make it clear that the figures implicit humanity has been realized on another plane of existence, in another dimension. This ‘other dimension’ is made explicit by the infinity of the gold background shining like a mirror. Despite the fact that four of the six saints are warriors, their faces are in deep repose, passionless, and indifferent to the world of constant change. The victory that they celebrate is not of the flesh but of the spirit. Empires born of men crumble and die as do the men themselves. In the fifteenth century as the City became an island in the midst of a Turkish sea, this realization must have recurred to many Byzantines.

Much of the mystical idealism of these icons is reflected in the frescoes of Mistra, executed between the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries. Mistra had become at this time, the haven of many artists and scholars who found life in Constantinople too confining. After the fall of Mistra in 1456 many of these refugees fled to Crete or Venice. Ironically, the Church achieved a hitherto unknown autonomy under the Turks. The patriarch, no longer a ‘thing’ of the Emperor, came to represent more the monastic element of the Church as what remained of the Byzantine aristocracy was understandably under Ottoman suspicion. Western influence, for a century or so, ceased to erode the fabric of Orthodoxy. During the period of the fifteenth to the seventeenth centuries, the Orthodox church was to see a final flowering of iconic art in the so-called ‘Cretan School.’