Neither rain nor wind nor sun nor, in fact, dead of night kept over one and a half million tourists from their appointed visit to the citadel last year. Even in antiquity, tourists flocked to the Acropolis, which so struck the fancy of the Hellenistic conqueror Demetrius Poliorcetes that he took up residence in the Parthenon.

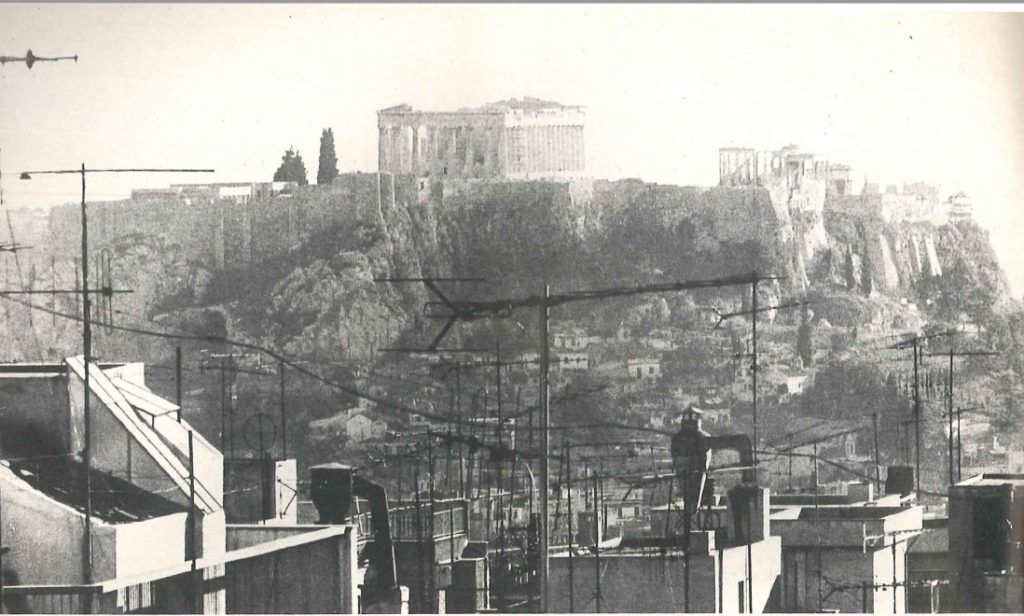

The word ‘acropolis’ means literally ‘high city.’ Every ancient Greek settlement had one, but few were as impressive as that of Athens. Plato believed that the original Acropolis extended eastward as far as Lycabettos, and that the entire early city was located on its heights. Although it is geologically part of the same range as Lycabettos and Tourkovouni, its bulk has not decreased appreciably since ancient times. Only modern man, with the subtle vibrations of machinery and the corrosive agents of pollution, has been able to threaten the solidity of the rock.

This great limestone boulder is the ‘seed’ of Athens and the primary reason for the location of the city. Its sheer sides offered safety to the Neolithic men who first inhabited it over 5000 years ago, while the springs around its base provided them with water. In the days of Theseus, the legendary founder of a united Athens, the Acropolis would have resembled Mycenae or Tiryns. Its brows, crowned with monumental Cyclopean walls, were so called because later generations imagined that only the Cyclops, the giant, one-eyed henchmen of Hephaistos, could have lifted the huge stones from which they were built. So strong was this Bronze Age citadel that when Mycenae and Tiryns fell, about 1000 years before Christ, Athens was never taken, a fact which remained a source of pride to Athenians of the Classical era.

When Athens began to evolve its democracy at the end of the 6th century, the Acropolis was transformed from a fortress into the religious center of the city. Athenians traditionally revered it as the site of the contest between Athena and Poseidon, when Athena won hegemony over Athens by producing an olive tree as a gift for the city. This was thought worthier than the salt spring proffered by Poseidon, and quite rightly, for Attic olive oil became so valued that its export was forbidden and it was offered as a prize in the annual games of the goddess.

Unlike churches, temples were rarely entered by anyone except priests and were in fact kept locked most of the time. They served as repositories for the rich temple treasures. Inventories of these treasures have survived, and they betray a certain pack-rat instinct: among silver vessels and gold jewellery are listed membra disjecta of disused statues, a discarded temple door, and a ragged dress the colour of a frog. Even the cult images were numbered among the assets—the gold on the statue of Athena could be removed and weighed.

THE regulations governing conduct on the Acropolis were not unlike those in effect today: dogs and food were not allowed, and one was not to relieve oneself in certain areas. Doubtless these rules were bent or broken on the birthday of the goddess when great processions escorted 100 cattle, offerings to Athena, up the difficult slopes to the altar. They were accompanied by citizens and slaves bearing the paraphernalia of sacrifice — jugs of water, trays of cakes, and parasols to protect the priests and dignitaries from the August sun. Afterwards the carcasses of the sacrificed cows were taken to the Kerameicos, and a gargantuan, state-subsidized barbecue ensued.

Athena, as patron of the city, held pride of place on the Acropolis, where no less than three temples were dedicated to her worship. There were in addition, shrines and altars of Zeus, Poseidon and Artemis, and sanctuaries of Dionysos, Asklepios, Apollo, Aphrodite and Eros clustered around its base. The intellectual Athenian of the 5th century may have been skeptical about his gods, but he was not going to risk ignoring them.

The extant structures were built to the greater glory of the goddess in the second half of the 5th century. However pious this may sound, their construction was financed by one of the greatest embezzlements of history.

It all started with the Persians, who invaded Greece in 480 BC, leaving behind them the traditional destruction. Among their devastations was the burning of the Acropolis, where the wooden roofs and overstuffed treasuries provided ample tinder. After the expulsion of the Persians, the Greeks vowed not to rebuild their ruined shrines until they had avenged themselves on their enemies. The independent city states showed uncharacteristic cooperation and formed an alliance to prosecute the war against Persia.

Such a scheme was of course doomed from the start. Gradually Athens, by virtue of a superior navy and wily statecraft, took over the alliance and appropriated its treasury, to the outraged but ineffectual objections of her allies. The honey-tongued Pericles, a consummate politician, engineered the coup, and he had grand ideas as to how at least a portion of the money was to be spent. What better propaganda than to build magnificent buildings on the Acropolis which, in those days before television and tall buildings, was visible from every part of the city? The temples, erected with painstaking precision, rank among the finest achievements of Greek architecture.

The expenditure was immense. The cost of the Parthenon alone has been estimated at 200 silver talents, equivalent in buying power today of about $ 10,000,000. Pericles encountered considerable resistance from his political enemies and from the frugal citizens themselves. But the buildings continued to rise and the program was carried on even after his death in 429 BC. Less than 30 years later Athens herself succumbed, exhausted and defeated in a war with her traditional foe, Sparta. She would never again enjoy such political power—nor would she ever again build such monuments.

THESE are the monuments that one sees today. Later buildings have been stripped away, and the 5th century structures remain, albeit sadly ruined. The history of Greece during the past 2500 years has been anything but glorious—civil war, tyranny, subjection to Romans, barbarians, Byzantines, Turks and Germans. But the Acropolis still stands, preserving the remains of the greatest moment of a civilization which, in a sense, begot our own. In the words of the historian Plutarch, writing in the 2nd century after Christ, when Athens was nothing but a quiet university town, the Acropolis ‘alone now testifies for Hellas that her ancient power and splendor was no idle fiction.’

For this reason as much as for the simple beauty of the buildings, visitors make the climb in the hot sun, guidebook in hand, and puzzle their way through a welter of walls and abstruse architectural terms. Perhaps the best time for a visit is by the light of the full moon. The effect of the still, ghostly buildings, bleached by moonlight to their pre-industrial whiteness, is enhanced by the unlikely sound of bouzouki rising from the boites of Plaka mixed with classical music floating up from Festival performances in the Theatre of Herodes Atticus. One can almost credit the folktale that when the gate has been locked for the day, the maidens who support the porch of the Erechteum descend from their posts, and gather in the Parthenon to mourn the loss of their sister, who was abducted by Lord Elgin and sold to the British Museum in the early 19th century.

The ‘Sound and Light’ show offers a less taxing way of enjoying the Acropolis. Although the ‘sound’ may be pure corn, the ‘light’ is impressive; red lights symbolizing the Persian fire illuminate the citadel at the climax of the show. The effects may be sampled, if you are poor and energetic, from the top of Lycabettos; or, if you are rich and tired, from an elegant and expensive restaurant across from the entrance to the Acropolis. From either vantage point the Acropolis appears, white silhouette against the black sky, rising from the web of other sounds and lights that is modern Athens, enduring symbol of Athena and her city.