These were the people of the Minoan civilization, so named for their legendary king, Minos. Their main palaces were in Crete, but they spread through the Cyclades as well and onto what was to prove a most unfavourable spot, the island of Thera. Thera is a volcanic island which even in the modern age has not been quiet. In 1956 a small eruption caused the destruction of 2,000 houses.

The time we are talking about begins around 3,000 BC. It was then that the Minoan civilization began to flourish, when its people were just emerging from the Neolithic or Stone Age and entering the Bronze Age. Its finest flowers of achievement blossomed immediately before its downfall, about 1,500 years later.

The Minoan civilization ended in quite the opposite fashion from that predicted by T.S. Eliot for the end of modern civilization — ‘not with a bang but a whimper.’ The brilliant Minoan civilization ended with a terrific bang circa 1520 BC. The eruption of Thera brought death and destruction from falling ash and the tidal waves and earthquakes that followed.

Its inhabitants had seemed safe. They constructed their houses out of stones joined by mortar mixed with earth, used wooden columns, plastered the walls and painted them with gaily coloured frescos. They built houses of two stories, and palaces as high as five stories, and enjoyed many refinements. Some of their plumbing systems still work today.

They ate meals of seafood, grains, beans, snails, and onions. They made their lives beautiful by decorating even the smallest or most commonplace items. They rested on beds with wooden frames to which hide mattresses were lashed. They sacrificed animals and birds (or images of them) to fertility goddesses. They kept written records (Linear A script which preceded Linear Β has been found at Akrotiri). On a clear day the inhabitants of Akrotiri, at the southernmost tip of Thera, could even see their ‘mother’ — the island of Crete.

When the volcano exploded, much of the population of Thera escaped through their own natural Early Warning System. They gathered together some possessions and put off in their ships — those same keeled vessels with which they had so successfully built their trade empire in the Mediterranean.

It is doubtful that they escaped very far. Where could they have escaped to?

The whole sea area of the Cyclades — from Delos, Siphnos, Melos, Naxos, and Amorgos, down to Crete and Karpathos and parts of Rhodes — saw destruction and ravages.

Crete, 70 miles from Thera, was hard hit. Tidal waves and hot volcanic ash inundated and buried the proud centres of the Minoan civilization and its humbler, smaller outposts. The tidal waves reached heights of 300 feet and in some cases, as in the port city of Amnisos, moved huge, heavy blocks of stone. Earthquakes and fire completed the destruction and the proud civilization sank into the sands of history.

Many people doubted that the Minoan civilization ever existed at all, except in myth, even though the careful historian, Thucydides, wrote in the 5th century BC: ‘Minos is the earliest ruler we know of who possessed a fleet, and controlled most of what are now Greek waters. He ruled the Cyclades, and was the first colonizer of most of them…’ But myth has a way of turning into history (and history into myth) and the Minoan civilization was revealed in all its glory after the excavations of Sir Arthur Evans at Knossos at the beginning of this century.

Evans was not the first to want to dig there. Schliemann, that Father of Greek Archaeology, had showed up in Crete in 1886. Frustrated in his attempt to purchase the site, he had given up. Evans was more successful. He bought the site, excavated it and even restored parts of the palace. He thought that earthquakes alone had been responsible for the final destruction. Others posited attacks by the Achaeans, the mainland rivals of the Minoans.

A different theory was first advanced in 1934 by archaeologist Spyridon Marinatos. The civilization had died out, Professor Marinatos believed, because of the volcanic eruption of the island of Thera. His hypothesis did not greatly impress the scientific world and even when he advanced it again in 1939 with more proof, the theory was found lacking. It was not until the 1960’s when he began excavations at Akrotiri that solid proof confirmed his theory.

Marinatos attributes his success in finding exactly where to dig to instinct. While excavating, he struck something more valuable than gold to an archaeologist: pottery shards that could be dated. Now, seven years after digging began in 1967, excavations are still in progress.

In addition to the finds on Thera, recent excavations at Kato Zarko on the eastern tip of Crete have provided more proof of Marinatos’ theory. There, too, evidence of volcanic ash was found in the remains of the buildings and the artifacts of a proud civilization.

Nature has often proved unkind to man. A volcanic explosion similar but of lesser intensity, rocked the Netherlands East Indies island of Krakatoa in 1833. By studying reports of this great tragedy, Marinatos acquired supporting evidence. The Krakatoa eruption killed 36,000 people and generated tidal waves of more than 100 feet. Marinatos puts the force of the Thera eruption at four times that of Krakatoa.

Excavations at Thera did not prove easy. Tephra, a thick coating of volcanic ash and pumice, covered the digging ground, as it does the island. Although its removal provides a commercially viable export product for the people of Thera, the tephra forces the excavators to proceed slowly.

What Marinatos has found is now in the National Archaeological Museum in Athens. To visit the exhibition is to travel back in time to 15 centuries before Christ.

As you enter the Minoan exhibit you come first to a series of photographs showing the difficulties of excavation — the propped walls, the necessary paraphernalia, the trucks, the girders, the corrugated sheds, the patience of reconstruction, the thousands of pieces that must be reassembled with careful fingers to accomplish a work so fastidious, the application of adhesive and gauze to the frescos, which are then pulled free to be put together again later. They show, too, the joys of a find: the revealed frescos, a stack of wine jugs.

Near the photographs is a layout map on which are marked (in Greek) the main buildings and streets excavated and the rooms in which the frescos were found. In this first room, too, are some pots such as a well-preserved one with three ‘horns’ on the spout.

In Room Two is a typical bed, or rather a reconstruction of a bed, and next to it are the clues with which the restorers worked. The bed had been made of wood. Over the centuries it had turned to dust leaving a cavity in the tephra in which it had been buried. Plaster was forced into the cavity and when it was set the ash was pared off to reveal the cast of a bed that had once existed. Even the placement of the thongs around the frame was revealed.

On the back wall are pottery and copper ware. One of the latter vases had a beautiful flowing design resembling waves that is still visible on the original and reconstructed on the drawing nearby. There are cooking utensils, a scale like the ones used even today by some manavides to weigh fruits and vegetables, saw-toothed cutting blades, knives and short swords, and votary pots. The head of an animal (votive or decorative) is here, looking like either a pug-nosed lion or a lion-eared pug.

There are seal stones, reminding one again of the comparison between the Minoans and the Japanese of Samurai days, as both delighted in perfecting minute objects. Here, too is a cruciform shape that resembles another found at Knossos. The speculation is that cross-worship was a part of Minoan lives just as was the similarly aniconic axe-worship.

Even the humblest pottery show designs from nature. This imitation of nature developed gradually. The earlier designers used geometric forms and when leaves, grape bunches, octopuses grain sheaves, etc., began to appear the artists, it seems, deliberately chose shapes from nature that had a natural symmetry approximating the geometric forms of an earlier day. Some abstract forms persist, especially the whorl — but even this could be seen as suggesting the rhythm of nature.

The dolphin is a favorite decoration on vases, votary pots and offering tables. One broken votary animal looks like a crude duck, and there are some female torsos, also votive in nature. In fact, all parts of the plant and animal world were associated with the goddess of fertility whom the Minoans worshiped: all symbolized her creative spirit, her life-giving force.

THE ewers are interesting, with their female breasts. These ewers, too, sometimes bear decorations of dolphins or plumes of barley. There is a beautiful collection of trough-shaped vessels, decorated with goats, birds, flowers, dolphins, and horses. A specialist, at present cataloging and photographing the finds in the second room which have not been previously published, speculates that they were probably used to carry fish.

Before leaving the room containing the special finds from Thera at the National Archaeological Museum, stop to examine the volcanically preserved food samples found at Akrotiri. Here, next to their modern equivalents, are fava beans, grains, and sea urchin spines, as well as snail shells and a primitive ‘souvlaki’ grill.

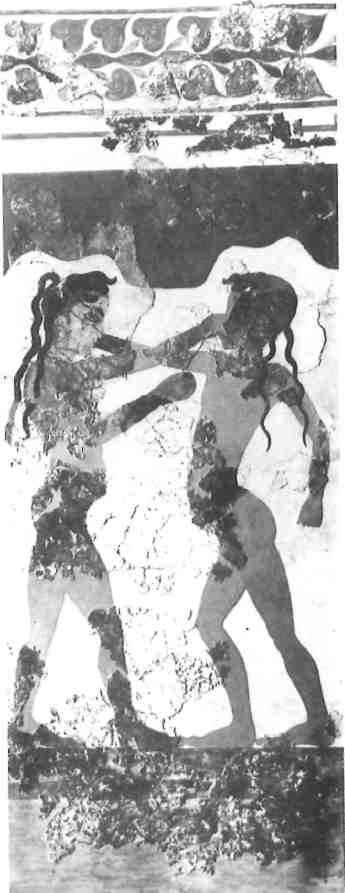

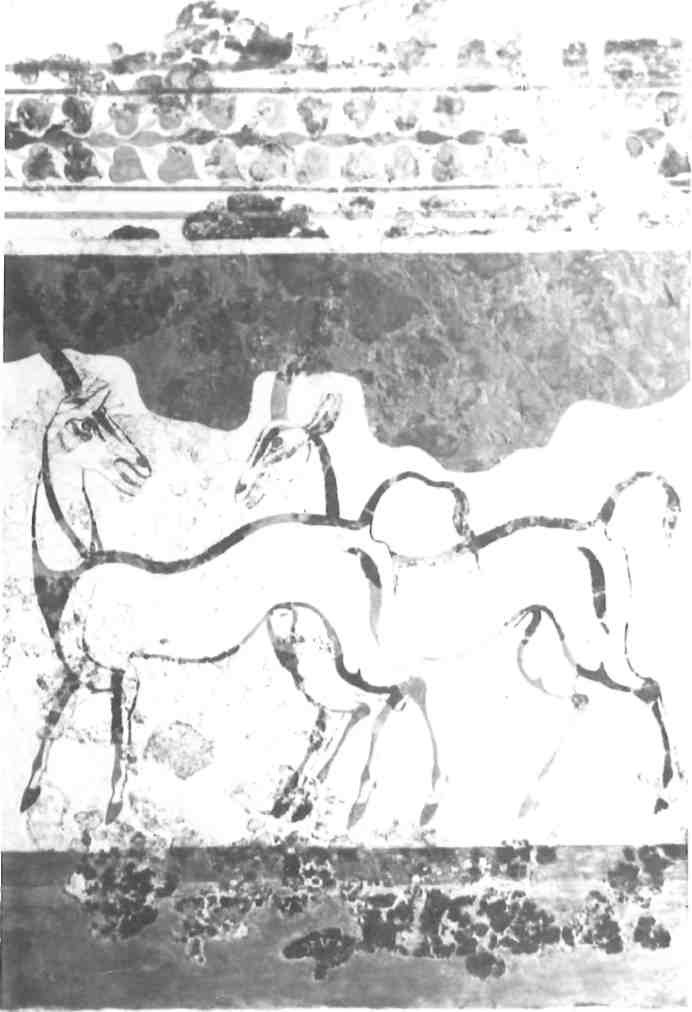

The final room of the exhibit contains the wall frescos. First come the antelopes. Antelopes were not indigenous to the Minoan world so either their sailors ventured as far as East Africa and saw these beasts or else the animals were once to be found in Crete and the Cyclades. Next come the boxers with their boxing gloves. Minoans liked contests and boxing was one of their favourite. The lightweights usually fought without accouterments, the middleweights in plumed helmets, and the heavyweights with helmets, cheek-pieces and padded gloves. Our Theran boxers wear only the gloves, so perhaps they are just young boys practicing and playing. The house where these frescos were found had a frieze of heart-shaped leaves that reminds one of Virginia Woolf’s essay on Kew Gardens where she writes of ‘heart-shaped and tongue-shaped leaves.’

The next fresco, which shows two lambs, is illustrative of the difficulties of reconstructing. The rough pieces are the original while the smooth parts are the modern fill-in showing what the completed original would have looked like. With so few pieces to go by, great scholarly care was needed to figure out what, which, and where.

Next come the famous blue monkeys with a gull flying in the upper right hand corner. The wall design contains the ubiquitous whorls.

On the end wall are the lilies and swallows. The lily and lotus flowers, common in Minoan frescos, seem to owe something to Egyptian influence, but even that which was borrowed from Egypt was transformed and given a Greek quality. The colours of all the frescos have faded to rust-red, grey-blue, and yellow-brown, but we know the Minoans liked gay colours so we can imagine the originals to have been more gaudy. Of course, in dark rooms one would want bright colours and a sense of nature being brought indoors.

The last of the frescos are interesting since, like the boxers, they give us an idea of what the Minoans looked like. We see in these frescos, for example, a female figure holding out a bowl of grapes. She is wearing large earrings and her hair is in a pigtail arrangement. Her dress is brown with bands of an ornamental design, its sleeves blue with a white flower design. As she does not have the bared bosom affected by upper-class women, perhaps she is a serving maid.

The next figures have bared breasts. Their hair is long and flowing and they wear earrings, and blouses and skirts with a kind of striped culotte effect held by a thong belt. The women’s cheeks are rouged. These wasp-waisted ladies seem to confirm what one perceptive historian remarked — that their figures resemble the double-axe so prominent in their religious symbolism.

In the museum exhibit is to be found proof of the characteristics ascribed to the Minoan people earlier in the article: elegant, amusement loving, desirous of beauty, ingenious, master builders and seafarers. All of these traits seem in some way to have entered the Greek character. After the destruction in Crete and the Cyclades, and, indeed, prior to it, Minoan artisans worked in the great Mycenean fortresses on the mainland, modifying Mycenean artistic achievements. In fact, date-wise the Late Minoan period, 1550-1050 BC corresponds to the Mycenean.

From the time of the thalassocracies (naval empires) of the Minoans to the present day we see that Greeks have always realized their dependence on the sea (It is not easy to overcome Greece by land. By sea it is easy if Greeks do not control the sea routes. The country’s modern wars prove this point).

Today Greeks still admire elegance and beauty, and many an artist still creates with the age-old traditional techniques. Modern Greeks like contests and games, and modern football seems to bring out all the blood lust as did the Minoan bull-leaping. Backgammon, a game we know Minoans played, is still played in village or quayside tavernas and in city kafenions. Greeks are still builders, although it seems building is proceeding apace with tearing down: and finally, as anyone who has lived here can attest, Greeks are still ingenious.