This ‘artistic’ aspect is not, however, clearly understood; in many cases icons are merely considered to be either ‘mementos’ of a trip to Greece or, even more unsettling, the final touch to a ‘with it’ scheme of interior decoration. In a sense, this is nothing new. We have all seen Buddhas turned into lampstands, or figures of Kuan Yin, surrounded by flowers, rising from the center of the dining table. Fortunately icons lend themselves less readily to such uses, but most people hardly realize the essential nature of this creatively embodied, religious experience.

Those whose sole experience of religious art — whether Catholic or Protestant — has been that of the West are unconsciously trained to see religious art as being primarily didactic, a means of instruction or edification. This particular purpose has, in fact, directed the development of religious art in the West. During the late Roman period and well into the Middle Ages, religious art was primarily a means of instructing the illiterate mass of peasantry — not to mention the aristocracy for whom reading and writing were ‘manual’ tasks better performed by monks and secretaries. (Charles the Great could barely sign his name). Religious art in the West has never been theologically defined. During the Renaissance it consequently was defenceless against the growing influence of humanism which ultimately destroyed its religious element. When all is said and done Raphael’s Madonna of the Sistine is just what she was — the girl next door.

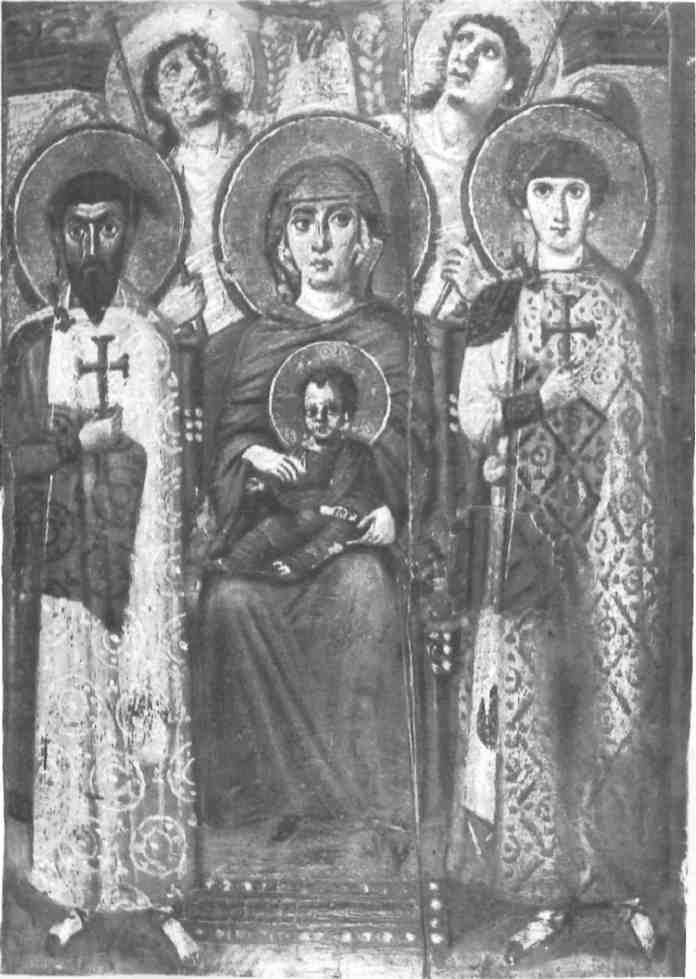

Faced with an icon of the Virgin and Child from the great period of Byzantine creativity, the viewer has no doubt that what is being represented is something more than a simple woman with her child. Too many elements jar the perception, elements which may not be entirely clear but which alert the viewer to an aspect of reality that one does not encounter daily.

The evolution of the Eastern Christian Icon falls roughly into five stages: the period of formation, from the 2nd to the 5th century, about which we know very little; the period of Justinian in the 6th century; the first Byzantine renaissance under the Macedonian and Comnenid Emperors from the 9th to the 13th centuries; and finally the Paleologue period which lasted until the fall of Constantinople in 1453. After this date we enter the realm of Post-Byzantine art which saw some of the greatest of the icons produced in the so-called Cretan and Ionian Schools, not to mention the icons of Russia and the Balkans which in a sense fall into a category of their own. The period of Justinian, from which few examples have survived, is certainly the logical place to begin a study of the icon as a peculiar aspect of the art of Eastern Orthodoxy.

The general meaning of the word icon is simply an image of something or someone. In the Orthodox East the term refers specifically to paintings of Christ, the Virgin, Angels, Saints or of scenes from the lives of these personages, executed on panels. Even more precisely, an icon is an object of formal worship. It both symbolizes a reality outside itself and embodies the actual presence of the person portrayed. In other words, an icon is a means of indirect communication with ‘transcendant reality’, since direct communication is not possible.

The theological justification for this belief (as it would seem to contradict the prohibitions aginst worshipping images and idols found in the Decalogue) is drawn from a text of St. Paul: ‘Christ is the image [icon] of the invisible God’ (Col. I, 15). In other words, the visible Christ is the very presence of the invisible Godhead. Christian theology in the 4th century went so far as to posit that God created the world in order that Christ could become man and thus in turn man could become God through the action of Divine Grace. This position, adopted by St. Athanasius and subsequently by the Church itself, forms the basis for an ultimate justification of religious imagery insofar as an image or icon of a ‘God-realized man’, i.e. one of the saints, is in some strange manner a reflection of the Eternal God.

Along these general lines of thought, the Council of Constantinople in 743 defined the role of religious art in the face of the iconoclasts who were adamantly opposed to it. This council, however, took great pains to insure that gross idolatry would be avoided. Henceforth images of Christ, the saints, etc., could only be two-dimensional panel portraits and the manner in which the images were to be worshipped was carefully defined and proscribed.

The definitions and views that were expressed by the Fathers at the Council were certainly rationalizations of an already existing phenomenon — a phenomenon which had been wreaking havoc in the Eastern Church from the time the iconoclastic Emperors first condemned the worship of images of any sort as idolatrous. Of even greater interest is the fact that the rationalizations were largely based on pre-Christian beliefs concerning images. It is in the earlier pagan world that the roots of the Christian icon, of both its form and use, are to be found.

It seems that the Christian icon derived from two sources. The first source would be the imperial lavrataov ‘portraits’ which were set up in every city of the Roman Empire as objects representing the ever-present reality of the Emperor. These lavrata were objects of formal worship as part of the state Imperial Cult. (Ironically, their refusal to worship these lavrata brought many Christians to their deaths). The second source would be the ‘mummy portraits’ of the Greco-Roman period in Egypt. The most famous of these are the ‘Fayum’ portraits which provided a means for communication with the dead. They were the objects of offerings and libations and were honored in the manner of ancestor worship.

In a highly complicated manner, the gradual fusion of these two forms of imagery produced the icon. As the center of the Imperial Cult was occupied by the icon of the Emperor, so the center of the Christian cult was occupied by the icon of Christ. Similarly, as the cult of the dead was represented by images of the dead who were considered to be efficacious in assisting the living, so the cult of the martyrs was inevitably expressed in images which drew one into a union with them. Such a union affirmed the Christian creed which proclaims the ‘Church of the living and the dead.’

Unfortunately very few icons from the period before the reign of Justinian have survived. The greater portion was destroyed during iconoclastic periods of the 7th and 9th centuries. Fortunately, however, a large number of 6th century icons were saved at St. Catherine’s Monastery in Sinai. This great monastic refuge was built during the reign of Justinian and appears to have received a large number of Imperial gifts from both the Emperor and from Theodora, his famous consort. As a consequence of its relative isolation in the midst of the Sinai wilderness, the Monastery seems to have ignored or to have been unaware of the iconoclast decrees and thus the icons were saved. Several of the surviving panels from Sinai were taken by Bishop Uspensky in the 19th century to Kiev where they now reside. The rest are still at the Lavra in Sinai.

What is immediately striking about all of the panels is the technique which relates them to the mummy portraits mentioned above. Each of the panels is made up of either single or double planed boards which were given a ‘tooth” to hold the pigments. This technique of painting is known as ‘encaustic’ and appears to have been used almost exclusively in the Fayum portraits and in the art of the Hellenistic period generally. While no lavrata of Emperors have survived it seems that these were probably painted resin to which small amounts of naptha were added. The paint was then applied by means of small spatula-shaped rods of metal. After application, the colors were fused by lowering a hot metal plate over the surface of the panel.

This process produced works of art with far greater durability than either oil or tempera. As the colors must survive the test of intense heat they retain their brilliance as if they were contemporary works. An interesting surface texture is also produced that is necessarily somewhat rough and irregular, casting subtle shadows which are made more striking because the technique, being somewhat ‘heavy,’ precludes great detail. Thus the artist’s approach to painting is neither linear nor graphic. It is dominated by considerations of mass and form which are distinguished by the colors and shadows.

The most famous of the 6th century panels at St. Catherine’s is a large image of the Virgin and Christ enthroned between St. Theodore and St. George, and two angels. The icon adheres closely to Imperial iconography: the Virgin is portrayed as an Empress on a throne. Significantly, the two Saints are warrior-saints and thus form the Virgin’s ‘guard’. The angels — direct iconographical descendants of the Victories of pagan art — fill in the scene, looking heavenward to the Hand of God that emerges between two palms of victory. Of great interest is the peculiar architectural form given to the background. Such a background is found exactly reproduced in a number of surviving Consular diptychs.

The dependence of Christian imagery on Consular iconography can be seen even more clearly in a 7th century icon of St. Peter also found at St. Catherine’s. Peter is shown in a formal Roman pose. Occupying the ‘clipeata’ are small heads of Christ, the Virgin and what is possibly St. Stephen. In a Consular icon; the ‘clipeata’ would have held the busts of the Emperor, Empress, and the heir-apparent.

Icon painting of this sort ceased by the end of the 8th century when the Church triumphed over the iconoclasts. After this ‘Victory of Orthodoxy’ icons were executed exclusively in tempera, and, as a consequence of the stringent definitions of the Council and the technical limitations and peculiarities imposed, icons assumed a markedly different form. The existence of a larger number of examples gives a more establish a rough outline of development. It will then be possible to consider questions of iconography and themes as they appear in the icons of various periods.