To your left are the old excavations, a pleasantly landscaped park, where ruins almost take second place to roses, oleanders and olive trees. To your right are the new excavations, a barren welter of walls, comprehensible only to the experts who uncovered them. You may see an archaeologist or two with a small team of workmen, practicing the annual rite of excavation, a tradition reaching back into the last century.

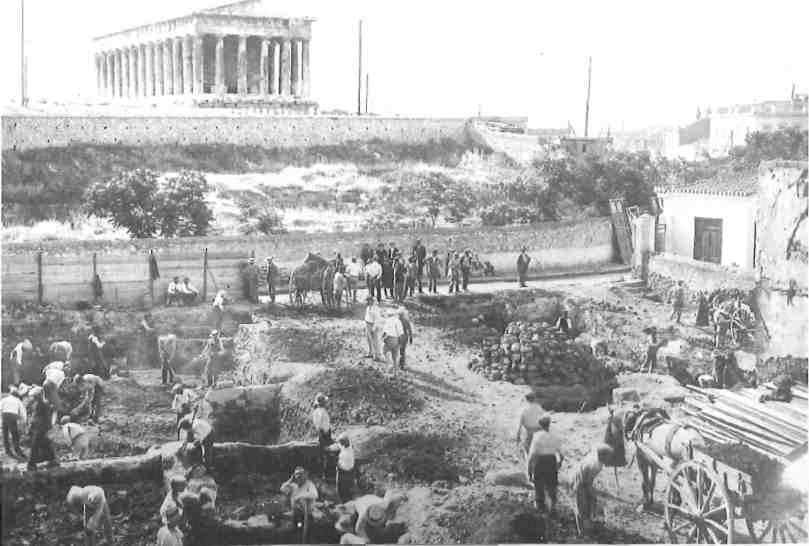

The railway is an appropriate way to approach the Agora, for the first major excavations there were done, not by archaeologists, but by engineers laying tracks for the extension of the railroad from Theseion to Kifissia in 1891. Willhelm Dorpfeld, Schliemann’s pupil and right hand man, was on the scene and managed to rescue several pieces of sculpture, now displayed in the National Museum. Dorpfeld had no idea that he was sitting in the middle of the Agora — indeed, he thought he had located it with his own excavations further to the south. Nonetheless, with the true archaeologist’s compulsion to record antiquities, he sketched and measured the bits of wall which the engineers had uncovered.

By the 1920’s the location of the Agora had been pinpointed, and a princely donation from an anonymous benefactor — who turned out to be John D. Rockefeller, Jr. — enabled the Americans to buy the necessary land.

So it was that in 1931 a team of young men and women, directed by Professor T. Leslie Shear, the father of the present director, began the tedium of demolition and the excitement of discovery. Most of the group were in their early twenties, fired with a rare enthusiasm for their work and for all things Greek. Many of them still work on the excavations, and some have made Greece their permanent home. With a stern injuction from their director against night life and partying during the digging season, they worked literally from dawn until dusk and beyond. They dug all day, and sorted, studied, and catalogued their finds in the evening. The excavations operated on a prodigious scale, in some years employing over 100 men, and lasting from February until November.

The notebooks which the excavators kept as a record of their work contain mostly mundane and technical information — how many men worked on a particular day, what sort of pottery was found in a particular trench. Occasionally, however, one catches a glimpse of a personality behind the network of minutiae. One disgruntled scholar, vexed by the seemingly endless number of inscribed wine-jar fragments which he had been called upon to describe, labelled one of them as ‘another filthy stamped amphora handle’ — earning a speedy rebuke from his superior in the records department.

The scene in 1933 on the first morning of Lent following Carnival (apokries) moved one excavator to purple prose. He wrote, ‘Their bodies quivered, their faces were distorted with pain, yet many of the workmen stumbled into the excavation shortly after the starting hour. Even the horses had hangovers. When the sun with unrelenting brightness emerged from behind a kindly cloud, here and there a man succumbed to alcoholic fatigue. The carnival is over, and the sad remnant of a Bacchic rout has returned to the hospitable cesspools of the Agora.’

There were sometimes disagreements among members of the staff, and these, too, find their way into the record. An exasperated excavator once complained, ‘Of those concerned with digging this area last year, three in number, each claims that one of the other two dug, or rather did not dig, this part.’

Some remarks strike a more sombre note. On April 28, 1939, it was observed that ‘the Fuhrer’s speech yesterday seems to have affected seriously neither the weather nor the international situation.’ A year later, the Agora staff was packing anc storing finds and records in bombproof shelters and preparing to leave Greece.

The story has a happy ending. When the archaeologists returned after the war they found their treasures and records intact. Other excavations had not been so lucky. In one museum pottery had been stored in carefully labelled boxes. The Germans discarded the finds and used the boxes for firewood. The returning archaeologists were presented with the useless labels by the Greek guard who had loyally preserved them.

The major work of the post-war years was the reconstruction of the Stoa of Attalos to serve as a museum and as storage and office space for the excavation. In an attempt to build a totally authentic reproduction, it was decided that nothing would be included for which there was no archaeological evidence. This posed a problem when it came to the lion-headed water spouts which drained the roof, for no fragment of the beasts’ lower jaws had been found. The necessary restoration was as simple as possible — the lions were not even given tongues. The first rainstorm proved this to be an error: the lions, instead of spewing the water out in a graceful arc, drooled it down their chins in a distinctly undignified manner.

The discoveries of the new excavations, which began on a grand scale in 1969, have been spectacular, uncovering much fine sculpture and pottery as well as the Royal Stoa, the scene of the preliminary stages of the trial of Socrates. There have been several unusual finds as well: a hoard of gold coins under the basement of a tourist shop, a cache of World War II munitions, and, in the cesspool of a mid-19th century house, a number of ointment jars which had contained a remedy for ‘inveterate ulcers, bad legs, sore breasts, sore heads, gout and rheumatism.’

So next time you’re on the train, look around you and, if you like what you see, get off at Theseion and walk down Hadrian Street to the entrance of the Agora: it’s still open from dawn to dusk.