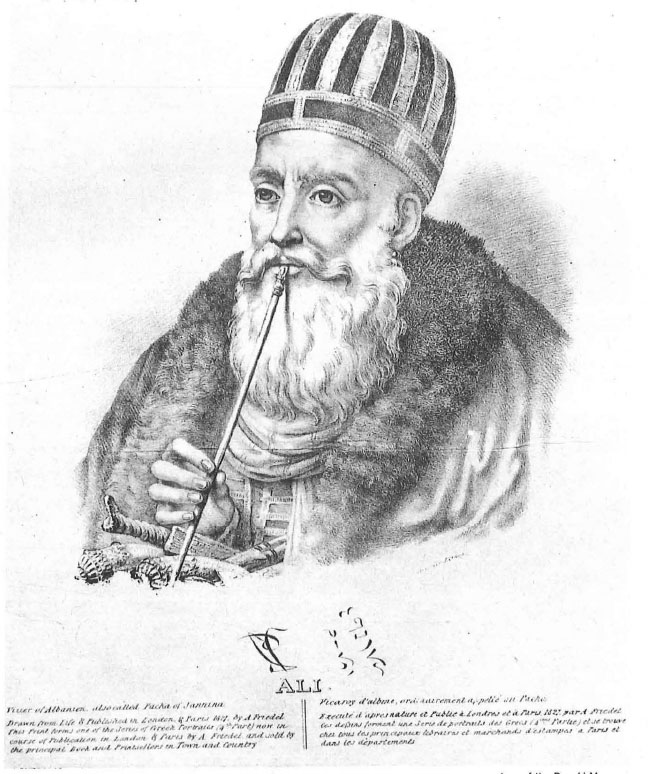

Ali of Tepeleni, the most celebrated pasha of loannina, ruler of Epirus, Thessaly and half of the territory in present-day Albania was born of Moslem Albanian stock, back in the days before the nation states of Greece and Albania even existed and the whole area was under the control of the Ottoman Empire headquartered in Constantinople.

One of the remarkable things about Ali, however, was not the unsavory incidents preserved in folklore — the heads that rolled, the enemies spitted and roasted alive, the seventeen loannina matrons drowned in the lake because the pasha suspected one of them of double-timing with his son and himself — but that he was able to amass for himself and his sons an extraordinarily large piece of the territory nominally under the Ottoman control, carving out an almost independent princedom. He treated in turn with the larger powers of the day, France, England, Russia, and his Turkish overlords as they jockeyed for power and real estate in this obscure corner of the world.

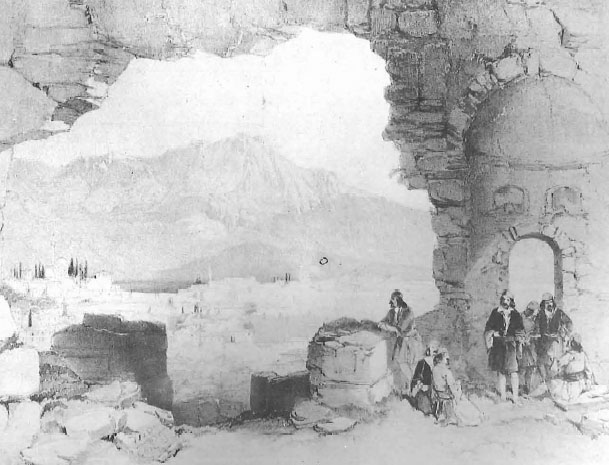

One of the pasha’s most famous foreign visitors was the English poet and philhellene Lord Byron, as evidenced by the prints and mementoes of Ali currently on view at the Benaki Museum in the exhibition ‘Lord Byron in Greece.’ Few vestiges of Ali’s palaces and seraglio remain. But the monastery guest house is still standing on the lake’s island where Ali Pasha met his death on one bloody January day in 1822. In the last 152 years the grass and weeds and trees have almost engulfed the low wooden structure blocking out the sun and trapping the shivery atmosphere of Oriental intrigue.

Ali’s story is thus an interesting diversion in the period between the decline of the Ottoman Empire and the rallying cry of Greek independence. Indeed, had Ali lived longer than 1822 he might well have fallen prey to the increasing numbers of Greek patriots whose activities were turning the area’s sparkling Zitsa wine sour in the cups of their Ottoman masters. But it took a reform-minded Turkish sultan, trying to salvage the Ottoman Empire, to gradually reduce the nepotism with which Ali and his sons administered their domains.

The fact that Ali was able to accumulate such power within the orb of Constantinople was an inherent feature of the Ottoman Empire. The administration of the Empire’s far-flung territories, including the lands of contemporary Greece and Albania, was divided into ‘pashaliks’ governed by local Moslem pashas. And if the local rulers kept the bribes flowing and the heads rolling, Constantinople’s inefficient bureaucracy and distance assured him of little interference from headquarters.

But we are getting ahead of our story. The Tepeleni of Ali’s birth around 1744 is now in Albania. Ali’s Moslem clan was the landed gentry, of beys in local terminology, of the area under the pasha of the more northernly town of Berati. The example of his parents might be ample evidence for any psychologist to explain the inhumanities that marked Ali’s character. The historian might remark that the atrocities that chill our ‘civilized’ blood today were commonplace at that time and place rather than extraordinary acts of barbarism. After the death of Ali’s grandfather, his father, Veli, murdered his two brothers to claim the family inheritance. And at his father’s death, when AH was still a child, his mother, Hanko, killed Veli’s other wife and her two children.

Ali got a start on his career like most of the young locals in one of the numerous bands of thieves. Thievery was a profession then like that of the Pindus Mountain shepherd or the Ioannina silversmith, and no doubt a good deal more lucrative. Distinguishing himself in this dubious line of work, Ali came successively under the mentorship of two of the most powerful pashas in Albanian Epirus, Kurd of Berati and Kaplan of Delvino. In 1768 he married Kaplan’s daughter and became heir to the Delvino pashalik.

Impatient for his father-in-law’s death, Ali contrived to speed it up a bit with a few well-chosen words to the envoys of Constantinople. When the Ottomans could claim only partial success in quelling some insurrections in parts of Albania and northern and central Greece, it was attributed to Kaplan’s negligence on evidence secretly supplied by his son-in-law. (At this time, he was also busy siring the old man’s grandsons, Muchtar in 1769 and Veli in 1771). Kaplan’s head fell and so did the pashalik, but not to Ali, whereupon the resourceful young man took another tack and married his sister to the new pasha, eventually murdering him and then awarding his widowed sister to his cohort. It is said the marriage was consummated beside the still warm body of the unfortunate spouse and pasha. Still the Royal Porte refused to appoint Ali to the pashalik of Delvino, awarding him the far lesser prize of Trikkala.

In 1788, a daring Ali rode into Ioannina with little more than a forged imperial decree declaring him pasha of the lake-side city. In the absence of the incumbent pasha, who was off skirmishing with dissidents, the feuding local beys could do nothing but press their foreheads to the supposedly royal document in submission. The Sultan, whose name Ali had invoked, later confirmed his lieutenant’s presumption.

Although it is the city of Ioannina with which Ali’s name is associated today, the new pasha viewed it as little more than a jumping-off place in his life-long campaign to obtain the more desirable provinces of Berati and Delvino.

Lack of space does not permit us to recount how the devious Ali in turn treated with or suppressed the local bandits or used Trikkala’s location on the main communication route between Constantinople and the western provinces for his own ends, or married his sons to his opposition’s offsprings, or stocked his storehouses with the wealth of his subjects, or meted out revenge to unwitting offenders.

The last decade of the eighteenth century Ali spent contriving to obtain the coveted lands of his birth. He made his first contacts with the French, English, and Russians cruising around the area’s seas, and skirmishing with the Suliots, the hardy people who lived in the crags and rocky plateaus between Ioannina and the coastal town of Parga.

If historians differ as to the sequence of incidents during the more than ten-year Suliot War, they are unanimous in their description of the bronze-skinned Suliot warriors, Christian Greeks of Spartan bravery and life-style. Clashing with Ali’s challengers at previously impenetrable mountain passes, egged on from behind by equally fierce womenfolk who traditionally took their places in line at the village well according to the bravery of their spouses. Treachery among the Suliots finally decided the contest in Ali’s favor. But the stuff of the folksongs was still to come. Ali permitted the defeated Suliot community to emigrate to Corfu, but he set up a lethal obstacle course for them. For example, his troops cut off a group of women and children on a high plateau ” near the monastery of Zalongo. Rather than submit to the certain atrocities that awaited them among Ali’s soldiers, they joined hands and voices in a traditional Greek dance, circling nearer and nearer to a high precipice. In a moment of frenzied singing, they flung the still-nursing babes and children over the cliff and then threw themselves onto the rocks below.

His dealings with the European powers yielded more concrete results than the conflict with the Suliots whose territories were nominally included in the pashalik of Ioannina anyway. From the French, Ali obtained the long-desired coastal towns of Prevesa and Butrinto, and a few years later he was ceded the jewel-like Parga by the British. French intervention with the Porte obtained the pashaliks of Lepanto and Morea in the Peleponnese for Ali’s sons Veli and Muchtar. But the European powers continually thwarted his designs on the Ionian islands.

The presence of so many interests in the area, however, provided Ali with a convenient justification for finally over-throwing the pasha of Berati, Ibrahim, who had succeeded Kurd, and for installing his son, Muchtar. He told the distant Porte that Ibrahim was consorting with the French who at that moment were in disfavor in the Ioannina seraglio.

It was at this period that one of Ali’s forays against a ring of counterfeiters yielded his best-known wife. Vassiliki Kontaxes, a lovely young Greek girl, offered herself to Ali in exchange for pardoning her father and family. But lest one entertain any illusions about Ali’s marital fidelity, up until his old age he kept his agents scouring the realm for beauties of both sexes to grace his harem.

One such extramarital episode provided the Sultan in Constantinople, already dissatisfied with the power accumulated by his lieutenant in Epirus, with the instrument of Ali’s destruction. It was one malcontent, Ismail Bey, who tattled to Ali’s son Veli that Veli’s wife was dallying with Ali. Ismail then logged one hairbreadth escape after another from Ali’s vengeance until he reached Constantinople and the sympathetic ear of the Sultan. The Sultan decreed Ali an outlaw in 1820 and dispatched Ismail at the head of royal troops to replace the old pasha. In March 1821, the Sultan replaced the unsuccessful Ismail with one very capable Khurshid who in January 1822 persuaded Ali to abandon his fire-damaged fortress in Ioannina, by then the only ground that could be called his own, with the promise of the Sultan’s pardon and permission to retain his wealth. With justifiable trepidation AH, then about 80, moved with Vassiliki and several loyal stalwarts to the small guest house in the monastery of St. Panteleimon, one of * several small monasteries still open to the public on the island in the middle of the lake.

The tidings brought by Khurshid’s emissaries could hardly have been to Ali’s liking, for the imperial decree did not grant his pardon, but demanded his head.

‘My head is not to be given up so easily,’ roared the old lion, as the folksongs immortalize him. Shots ensued. Today, the caretaker of the guest house will point to bullet holes in the wooden floor where Khurshid’s men fired up at Ali’s party in the upper storey from below. Bleeding from three gunshot wounds, Ali was decapitated on the spot by three strokes of a notched cutlass. His head, stuffed with cotton and spices, was sent to the Sultan in Constantinople, accompanied by the long-suffering Vassiliki.